NASA and soft power, againby Taylor Dinerman

|

| Soft power is more than just prestige—though that is a part of it—but it flows naturally from real achievements. |

Translating achievements into soft power is the work of thousands of creative cultural entrepreneurs. These people cannot be conjured up out of nothing; they have to exist within a supportive social environment. It was the lack of this environment that doomed George W. Bush’s rather weak efforts to enlist America’s soft power on behalf of his pro-democracy agenda.

NASA and the space industry, on the other hand, do have a supportive network amongst the creative elite. They have not been able to mobilize it effectively due to obvious divisions and distractions. For example, the industry has been able to put together a coalition for space exploration, but is has yet to make much of an impact due to its Washington-centric focus. A support system based on new ideas would concentrate on building and mobilizing support from the people who make movies, TV shows, and videogames.

Beyond this, soft power is often seen as a tool or instrument of foreign policy. Thinking of it this way seriously handicaps any policymaker who wants to use it as a part of American strategy. This simply will not work. One might as well try and tie up a package with silly string rather than twine. Yet soft power can be created by involving other nations in challenging, difficult, and rewarding programs like the International Space Station.

Both Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton saw in the ISS a useful too for sustaining and cementing important relationships. The US-Japan alliance has been strengthened and improved thanks to the ISS. More importantly, the space station program has kept lines of communications open between Washington and Moscow that would otherwise not exist. Even in times of tension the US and Russia maintain a 24/7 combined operational system of coordination that would be unthinkable in any other context. The ISS is not a tool of US influence on Russia, but without it there would be less trust and understanding on both sides. The other ISS partners have their own roles, but the US-Russia nexus is the backbone of the project.

Now that the ISS is almost finished and as the US tries to move towards the next stage of its human spaceflight program questions are being asked and a typical Washington Kabuki dance is underway to determine what changes, if any, need to be made to the Constellation program. Soft power considerations will probably not have much impact on the Augustine commission or on Capitol Hill, but inside the White House they will play a role just as they have in every civil space decision since Eisenhower confronted the impact of Sputnik.

The program may come out politically unscathed from both the budget process and from the Augustine commission’s quick look study. If so, and of the Ares 1-X test now planned for sometime after the end of August goes well, a new set of questions needs to be asked about how much does the US want to integrate other nations into its exploration program.

| If, however, it is excessively restrictive or, alternatively, if its abandons its leadership role, then NASA will gradually cease to be a significant national asset and become just another special interest pleading for a handout. |

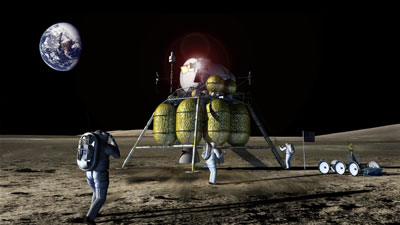

Under the Bush administration the answer went something like, “We are open to cooperating on everything except items in the ‘critical path’ roughly defined as the Ares launchers, the Orion capsule, and the Altair lander.” Other nations decided for the moment to keep their distance and to wait and see how the program progressed. If things go as planned then sometime in 2010 or 2011 the administration and NASA will be faced with the need to figure out a way to integrate other spacefaring nations into the Constellation architecture.

At that point there will be an opportunity for the US to create a new source of US soft power. It could be done by inviting the other spacefaring nations to join in an administrative partnership to control the lunar base and its operations. It could be an offer to help one or more of the other partners to build their own lunar facility. Or it could be something else. In any case, as long as the US appears to be open and generous in its plans for the Moon it will gain soft power.

If, however, it is excessively restrictive or, alternatively, if its abandons its leadership role, then NASA will gradually cease to be a significant national asset and become just another special interest pleading for a handout. The new leadership at the space agency has a set of tough decisions ahead of it. Whatever choices they make, the role of NASA as a creative part of America’s worldwide influence is a powerful argument for the agency.