Elements of a 21st century space policyby Peter Garretson

|

| Most fundamentally, a 21st century space policy must address the structural issues in our national space enterprise which impede forward motion and have prevented satisfying cumulative capital gains in our space program. |

Every phrase should be guided by the advice of Parag Khanna: “First, channel your inner JFK. You are president, not emperor. You are commander in chief and also diplomat in chief. Your grand strategy is a global strategy, yet you must never use the phrase ‘American national interest.’ (It is assumed.) Instead talk about ‘global interests’ and how closely aligned American policies are with those interests. No more ‘us’ versus ‘them,’ only ‘we.’ That means no more talk of advancing ‘American values’ either. What is worth having is universal first and American second.”

Second, since the last policy came out in 2006, we have learned a lot more about what kind of enabling policy framework it will take to be a true second generation industrial space power and spacefaring civilization. There are a host of new issues and paradigms that are not addressed in past space policy directives, and it is the expectation of the space community that the new administration will address these.

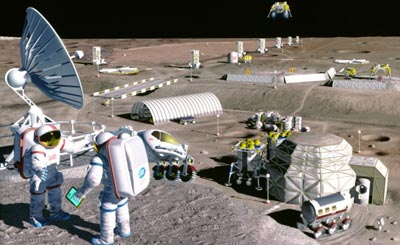

Most fundamentally, a 21st century space policy must address the structural issues in our national space enterprise which impede forward motion and have prevented satisfying cumulative capital gains in our space program. Paradigmatically, the new space policy and accompanying vision must redress the unbalanced emphasis in our civil space program from a narrow focus on science and exploration toward an appreciation and enablement of development, exploitation, and expansion of humanity’s sphere of economic activity.

Right now, there is no comfortable place for space applications that are not discovery science, exploration, military, or established services. For the most part, it leaves out—or at least leaves nebulous, unconsolidated, and without a critical mass—programs and development efforts for infrastructure, industrialization, space resources (survey and process maturation), non-traditional and persistent security situational awareness, and global utilities—all of which, to a far greater extent than a discovery and exploration program, will determine the elements of future United States comprehensive national power. Without providing a consistent advocate, a central funding stream, and a central planning process, the support base will remain scattered and progress will be unsatisfying.

The policy should provide the broad brushstrokes that should be followed up with some very specific actions during the first term of this administration, to include:

1) Publish an inclusive “Vision for Space Development” (VSD) to accompany any vision for space exploration. This vision must be focused on opening space as a medium for the full spectrum of human activity and commercial enterprise, and those actions which government can take to promote and enable it, through surveys, infrastructure development, pre-competitive technology, and encouraging incentive structures (prizes, anchor-customer contracts, and property/exclusivity rights), regulatory regimes (port authorities, spacecraft licensing, public-private partnerships) and supporting services (open interface standards, RDT&E facilities, rescue, etc.).

If NASA is not to be focused or provide leadership in this area, an alternate center or centers of excellence, funding, and support should be established to nurture those components of academia, state space agencies, national labs, industry, and international partnership that are currently stymied by a NASA unwilling to lead in areas peripheral to discovery robotic science or human exploration. One option would be to dismember NASA, putting the more commercial friendly space-sections (Ames, Glenn) under the Department of Commerce Office of Space Commercialization (DOC/OSC) or Corps of Engineers, aviation-related research under FAA, and leaving NASA to focus on its historical interests, or further breaking it up, moving space services and robotic exploration to NOAA or NSF, and returning national launch and human exploration to the DoD, or entirely to the commercial sector.

The most important and transformational program at NASA is not Constellation, but rather COTS and its innovative partnership and prize programs, which are focused on a meaningful and more important sustainable expansion of a viable American capabilities. The test is not whether NASA can do it, but whether NASA has opened and transferred it for auto-catalytic development with US industry.

| While the concept is not yet at a point where a mega-program is required, space-based solar power is at least as promising and scalable as fusion, and deserves a commensurate developmental program. |

Rejection of sovereign claims must not extend to a domain hostile to private property that has served humanity so well, and surrender to communalism that might cost us our long-term survival—we do not want humanity’s future in space to look like Antarctica, barren and devoid of the splendor and diversity of human activity except for science. Therefore caution should be exercised when considering steps such as becoming a signatory to the Law of the Sea and Moon Treaty which foreclose the opportunities to future generations of property rights and set up wealth and technology transfer mechanisms which subdue incentives for private exploration and risk.

2) Establish a separate funding line for space infrastructure and development projects to compete and flourish. This could be in NASA or elsewhere (Department of Commerce, Corps of Engineers), but without it significant progress will not be possible.

3) Direct the creation of an interagency and international vision for persistent, space-derived non-traditional security (space and Earth environmental) awareness. From climate and disaster warning, to space debris and solar weather, to global crop, fishery, and health monitoring, there are a host of things we would like to know about our Earth and space environment on a persistent basis. We need both a unifying paradigmatic structure for this, as well as a guiding interagency vision.

One obvious component of this, which leads directly to the next point, is the adoption of the broader and more inclusive European conception of Space Situational Awareness.

4) Establish a lead agency, and supported/supporting relationships for the now fully established asteroid/comet hazard. Since the 2006 policy, the importance of this issue simply cannot be ignored. The will of the Congress is explicit, having tasked both the OSTP and the NRC, and there are long-standing and unacted-upon recommendations from as early as 1990, recently re-affirmed by 2007 AIAA, 2008 USAF, and 2009 IAA conferences and reports.

The optimal arrangement would be to give the operational mission of warning and mitigation to a combatant command—USSTRATCOM today, and hopefully a reconstituted USSPACECOM in the future—exercised through the space security responsible agency—USAF today, and perhaps a USAF Space Corps or separate Space Force or Space Security Department in the future. NASA, NSF, NRO, MDA, and DTRA would all have formal supporting roles. For the consequence management, Department of Homeland Security should have primary responsibility.

5) Establish a lead agency—preferably ARPA-E—with a clear mandate and initial funding for space-based solar power, for a developmental program to achieve long-term economic viability. While the concept is not yet at a point where a mega-program is required, SBSP is at least as promising and scalable as fusion, and deserves a commensurate developmental program. There would be strong benefits to an international effort to experiment and demonstrate component technologies, analogous to ITER. Both Japan and ESA have developmental efforts, and the US should play a leadership role in the greenest of all renewable energy technologies, that is also potentially the largest and most lucrative global utility and launch market.

Space Solar Power has not done well historically under NASA, as it has viewed it as a distraction from human and robotic exploration, and does not consider energy or commercialization in its mandate. NASA would do better as a supporting supplier of technology to a DOE office with a specific mandate, such as ARPA-E, which has a mandate to foster research and development of transformational energy-related technologies, and holds the purse strings.

6) Restore developmental funding and mandate for long-term developmental and revolutionary technology development, specifically: reconstitute the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC); restart NASA’s efforts in advanced propulsion and Breakthrough Propulsion Physics (BPP); give far greater emphasis to Space Resource Utilization development; and affirm DARPA, DoD labs, and DOE’s mandate to contribute in these areas. It would be exciting if this Democratic administration displayed the vision of previous Democratic administrations in developing truly strategic long-term propulsion, such as the NERVA nuclear rocket program.

7) Provide the Security Space enterprise with the tools it needs articulate its needs, problems and potential contributions and compete on a level playing field for resources. Those tools include sufficient internal controls on budget and personnel development and promotion, and a truly independent voice before the programmers, authorizers and allocators.

| Space tourism and the surrounding space entrepreneurial community is creating new jobs and industrial knowledge that are moving us toward routine, reusable, aircraft-like, and low-cost access to space. |

“Security Space” faces a number of structural problems. Although space is fast-becoming a co-equal domain for military competition, with vastly different characteristics than land, sea, or air, it remains subordinate across the various branches as a support function. Its principal provider, the USAF, is not its principal customer, and will always have core considerations (air superiority) that trump those of space. Budget, personnel, and requirements are fragmented between the military and intelligence communities. Optimal development of security space professionals is likely to be quite different than recent development tracks that stressed operationalization, and tours in missiles to balance the requirements shape the size and seniority of the force to more general requirements. Operationally, space falls under USSTRATCOM, which many consider an over-tasked combatant command (COCOM). As a result, military space lacks truly independent control of its personnel, promotions, ability to develop a competing doctrine, and ability to argue directly for resources. The situation has led various thinkers to suggest a fenced budget, a distinct personnel system, separation of space professionals from ICBM tours, consolidation of AFSPC and NRO, the creation of a Space Corps within the USAF, a separate COCOM for space, and even a separate space force.

8) Recognize space tourism as the strategic industry that it is, and prioritize an enabling policy and regulatory regime to sustain and develop US leadership. Space tourism and the surrounding space entrepreneurial community is creating new jobs and industrial knowledge that are moving us toward routine, reusable, aircraft-like, and low-cost access to space. As with other infant strategic industries, government has a role to play in conducting targeted and responsive pre-competitive research (as was the focus of NACA before becoming NASA), establishing prizes and anchor contracts, as was done in aviation.

9) Give a mandate and encouragement to state space agencies (Space Florida, California Space Authority) to take a leadership role in space infrastructure development, and develop a supporting policy to allow typical infrastructure funding (bonds) to apply to space infrastructure, and conceive of a matching funds program not dissimilar to our Federal Highway Trust Fund.

10) Engage the international community on the future of safe space operations, including the need for active space debris remediation, space traffic management, and the creation of an International Civil Space Organization (not unlike the International Civil Aviation Organization) for coordination, standard-setting, and regulation.

11) Finally, the new space policy must unshackle American industry and academia to participate, contribute, and compete fully and much more freely in the global marketplace and global partnerships, and stem the tide of erosion and export of our industrial base into “ITAR-free” zones and products. It must make a clear and bold break from this unique, self-imposed disadvantage, which particularly hits hard the small entrepreneurs who are the core of our innovation machine, and lack the resources to pay the enormous ITAR reverse-tariff in dollars, manpower, or time. It must also provide the top-level direction and resources to reduce the administrative processing time for visas that impede our strategic partnerships.

| A space policy for the 21st century must not be about grudgingly protecting our limited advantage today, but rather aggressively go after the substantial gains of emerging new industries and endeavors that will be America and the world’s spacefaring future. |

Fundamentally, the policy must recognize that the winds are changing, and demand a new conception and strategy for international security. We cannot prevent the expansion of actors into space nor the expansion of knowledge about ourselves through satellite-based observation. We can either fight the wave of this new transparency or surf it, recognizing the benefits to global stability and security it provides. In such a climate, we may have more to gain from sharing our imagery and space situational awareness, and encouraging the same from others than hoarding it. If we “crowd source” this vast open-source intelligence analysis problem to the billions of eyes and thousands of “little brother(s)” out there watching Google Earth and Microsoft Virtual Earth, we might be impressed with the positive effect that such transparency might provide.

A space policy for the 21st century must not be about grudgingly protecting our limited advantage today, but rather aggressively go after the substantial gains of emerging new industries and endeavors that will be America and the world’s spacefaring future; not just giving lip service to space as the final frontier, but developing it. A space policy that finally looked beyond just discovery science and exploration and gave sufficient emphasis to nurturing the sprouts of the industry and infrastructure that put us on the path toward true spacefaring, survival, security, space development, and frontier opening, however less glamorous than a big rocket program, would be quite a legacy indeed.