Still on the ground floorby Jeff Foust

|

| A core group of space elevator advocates—including some who have survived the ups and downs, so to speak, of the last few years—are actively trying to rekindle interest and activity in the concept. |

That burst of interest, though, hasn’t translated into major progress in the development of a space elevator, at least at the pace its backers previously planned. After the NIAC grant ended additional government funding, from NASA or elsewhere, wasn’t forthcoming (NIAC itself closed two years ago, a victim of changing funding priorities within NASA). LiftPort—which sought to bootstrap the space elevator by developing key technologies and spinning them off into other, commercial applications—ran out of money in early 2007. The momentum gained a few years ago was in danger of being lost.

However, a core group of space elevator advocates—including some who have survived the ups and downs, so to speak, of the last few years—are actively trying to rekindle interest and activity in the concept. At the 2009 Space Elevator Conference, held earlier this month at Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond, Washington, those enthusiasts gathered to talk about technology, policy, business, and related issues related to the space elevator, as well as better organize their efforts.

LiftPort’s return

The turnout for the four days’ worth of technical sessions at the conference was modest: about 70 people, according to conference organizers (a pair of “Space Elevator 101” introductory sessions for the general public brought in 85, while a couple hundred people attended a free presentation the evening before the conference started.) The conference did attract researchers and others from across the country, as well as Canada and Japan.

Among those in attendance—as well as one of the key participants—was Michael Laine, the founder of LiftPort. For several years Laine funded the company by leveraging an office building he owned in Bremerton, Washington, that also served as LiftPort’s headquarters. However, in April 2007, when Laine was unable to secure another round of refinancing of the building, he lost his primary asset to foreclosure. With no near-term prospects for raising funding, Laine soon put the company into mothballs.

What followed was something of a wilderness period for Laine, where he kept a low profile. “I spent about a year being pretty angry when everything collapsed,” he said in an email interview after the conference. “Then, once the anger subsided and I was thinking a little more rationally, the dust was still settling.”

Last summer, he went to the International Space University (ISU) summer session in Barcelona. “I went to ISU as a litmus test for whether I cared enough about this stuff to stay with it,” he said, saying he could have opted for a more conventional—and potentially lucrative—career in finance or investment. However, his time at ISU reenergized him and convinced him to stay in the space field.

Since ISU Laine has been working on a “version 2.0” of LiftPort. “Only recently have enough good things started coming together,” including contracts to do research and some development funding, he said at the conference, “that I can feel confident to get back into the game.”

Laine said after the conference that LiftPort would do “what it should have done in originally”, and focus on commercializing precursor technologies, starting with tethered balloons for communications and observation, along with some robotics work. He said he also sees LiftPort getting involved, in 12 to 18 months, on a “venture capital/private equity project” to help invest in these technologies. “That’s where I think we’re going to be spending our time and energy, in the precursor stage that will move the elevator forward, but at the same time will be less risky for myself and my teams,” he said.

| Laine went to the International Space University as a “litmus test” to see if he wanted to stay in the space business. “For better or worse, it is the right place for me.” |

He acknowledged at the conference that there are some people in the space elevator community who would rather not see LiftPort revived, given the negative press surrounding its financial problems. Those people, Laine said, “believe that some of the damage we did taints us.” Part of the problem is that much of that damage is based on rumor, not fact, such as claims that that LiftPort was fined $20,000 by the Securities and Exchange Commission. “That rumor got away from us. It was not true, it has never been true,” he said, saying that instead the company got a warning for misfiling one page of a 100-page document.

LiftPort’s past problems aren’t completely behind it yet, Laine said, although the situation has improved to the point where he can focus on the future of LiftPort, and the space elevator. “For better or worse, it is the right place for me.”

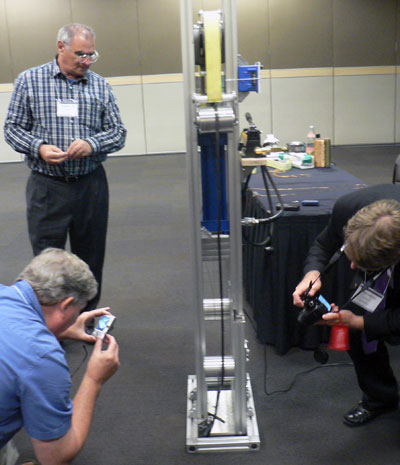

Conference attendees inspect the sole tether competing in the tether strength challenge this year after it broke. (credit: J. Foust) |

Prize challenges

Much of the interest in and publicity about the space elevator in the last few years has centered around a pair of prize competitions, for power beaming and tether strength, collectively known as the Space Elevator Games. The competitions are run by the Spaceward Foundation with the prize money—yet to be awarded for either competition—provided by NASA’s Centennial Challenges program.

Of the two, the power beaming competition has gotten more attention, perhaps because it’s more visually compelling: robots climbing up a vertical ribbon using power—in the form of reflected sunlight, spotlights, or lasers—beamed up from the ground, a concept of operations at least superficially similar to how an actual space elevator would operate. Past competitions have attracted teams from the US and Canada that on some occasions gotten very close to meeting the climbing speed requirements for winning prize money.

While teams have gotten close, each time the competition organizers have made the contest more difficult. “If we just kept it the same they would win the prize,” said Ben Shelef of the Spaceward Foundation. “These are large dollars, so we think it’s got to be difficult.” So after requiring climbers to ascend a 100-meter ribbon in the previous competition, in October 2007 in Utah, the foundation decided that the next time around the competition should be even more difficult: a one-kilometer ribbon.

That poses technical challenges not just for the competing teams, but for the competition organizers as well: the previous method of holding up the ribbon on a crane wouldn’t work for a one-kilometer ribbon. Instead, this summer the competition organizers, working at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base, tested suspending the ribbon from a helicopter. That, too, has posed some problems.

| The tether strength competitio doesn’t get the same amount of attention because it lacks the “shock and awe value” as the beamed power challenge, Shelef said, but could in the long run be more important. |

“We spent a good year with industry experts working it, and we’re still not quite there,” Shelef said of efforts to have a helicopter properly deploy the tether and maintain tension on it. He had hoped to have everything in place to run the competition in July or early August, but were stymied by problems during one test, when the helicopter pilot decided not to follow plans to use GPS to stationkeep and instead used visual references. During the test the helicopter drifted from its position and, when the pilot tried to compensate, he overcorrected, causing the tether to detach from the helicopter and fall to the ground.

“We’re going to fly this again and we’re going to use a pilot who is ‘instrument flight-minded’,” Shelef said. He didn’t give a timeframe for when they would be ready to hold the competition, but he did say they had to wait a month before the helicopter would be available again because it was being used for firefighting. Shelef said that it appeared that at least three teams would be ready when the competition is finally held later this year. Four other teams are actively building hardware, he added, but are not in an advanced state.

The tether strength competition, on the other hand, doesn’t get the same amount of attention because it lacks the “shock and awe value” as the beamed power challenge, Shelef said, but could in the long run be more important. “Strong tethers are important, probably more important than power beaming,” he said, because they have multiple applications well outside the realm of space elevators. The competition is also much simpler to run: no cranes or helicopters are needed, only a simple device to apply force to a tether until it breaks.

The 2009 strong tether competition, held during the conference in an adjoining room, featured only one team, from Shizuoka University in Japan. (A second team, from New Hampshire-based Nanocomp Technologies, bowed out at the last minute, according to Shelef, having run out of time to complete their tether.) They brought a tether made of carbon nanotubes that was wide and thin, resembling a thicker, stickier version of videotape. Given the promise of CNTs to make a space elevator possible, there was some optimism in the audience about the prospects of this tether.

As it turned out, the competition was anticlimactic. The tether was put into the device, alongside a “house” tether made of a commercial material, Zylon; the competition tether had to be at least as strong as the house tether to qualify for any prize money. Force was applied to the tethers—and almost immediately the CNT tether snapped, at a breaking strength of only approximately 265 newtons (60 pounds-force). Why the tether broke so quickly wasn’t clear, although the form it took—a flat ribbon, instead of threads twisted together—may have played a role.

Afterwards, two house tethers were pitted against each other: one finally broke after a force of about 12,500 newtons (2,800 pounds-force), demonstrating just how far CNT tethers have to go just to compete against existing materials, let alone have the strength needed for a space elevator. The outcome, though, wasn’t necessarily surprising to Shelef, who expected even before the 2009 competition that it would take some time before a tether would be strong enough to win. “We expect that competition to lag behind power beaming a good year or two,” he said.

One end of the competition tether, made of carbon nanotubes, after the competition. (credit: J. Foust) |

Is a space elevator inevitable?

While part of the conference was devoted to technical issues related to space elevators, as well as potential applications and even the effects a space elevator would have on military space uses, there were also sessions at the conference on more practical near-term issues, from public relations to development of business plans to Laine’s discussion of “lessons learned” from his experience with Liftport. One outcome of the conference along those lines was a plan to establish a “Space Elevator Institute” (SEI), a virtual organization to coordinate academic research on space elevator topics. Arun Misra, chair of the mechanical engineering department at McGill University in Montreal, along with Stephen Cohen, a graduate student there, have agreed to host the first “node” of that institute.

| Laubscher believes a space elevator is inevitable because of the potential of CNTs. “The public is going to be so used to carbon nanotubes, so enamored with carbon nanotubes, that they’re going to expect us to, and demand that we, build a space elevator,” he claimed. |

Laine said after the conference that this institute could help commercial ventures like LiftPort, coordinating the research and development that is difficult for a private company to do on its own. “So the SEI will help develop the questions, and then farm out research topics to develop answers,” he said. “Frankly, I think it is years overdue.”

The problems faced by LiftPort, and the lack of major progress in recent years, have dampened the enthusiasm the community once had for the space elevator. No one is talking any longer about having a space elevator operational in 2018. Even LiftPort quietly adjusted the countdown clock on its web site back in late 2006 from 2018 to October 27, 2031. Laine now says it may take even longer than that: perhaps somewhere between 2035 and 2045.

The core proponents of the concept, though, remain undaunted by these near-term problems. Bryan Laubscher, a former Los Alamos scientist who is now president of Odysseus Technologies, gave a presentation at the conference with a provocative title: “The Inevitability of the Space Elevator”. He argued that CNTs represented a new material age for civilization because its lightweight strength would allow it to eventually be used in a wide variety of applications. “By the time all this happens, the public is going to be so used to carbon nanotubes, so enamored with carbon nanotubes, that they’re going to expect us to, and demand that we, build a space elevator,” he claimed.

That assumption of inevitability, Laine said, is also shared by the media. “We’re always asked, ‘When is this thing going to be done?’ The press just leaps to the conclusion, the expectation, that it is inevitable,” he said in a conference presentation.

“We’ve spent the last six or seven years almost exclusively dealing with the challenges,” Laine said, but he believes there’s a lot more work the space elevator community needs to do to understand exactly what all those challenges are if they are going to be successful on any timetable. “I really do believe that we haven’t even scratched the surface of all the potential problems out there. We just don’t know enough to ask the right questions yet, so it’s clear we couldn’t possibly have all the answers.”