Which way is up?by Dwayne Day

|

| Although it has become a cottage industry today to lay blame at the space agency itself, it is clear that Bush did not continue to publicly, politically support the plan he originally established, and over time his administration drained money from the space agency. |

So here we are, with a space exploration program that cannot be executed without at least the return of the budgets that were originally promised. The recently completed Review of Human Space Flight Plans Committee, better known as the Augustine Committee, has thrown all of those issues, and more, into sharp relief. The Committee’s work was the subject of a half-day symposium held on Monday, September 28, by the Space Policy Institute of The George Washington University. The speakers came from industry, the Department of Defense, academia, and Congress to discuss various aspects of the issues raised by the Augustine Committee. One thing that became apparent during their discussions was that the issues are much more complicated and nuanced than most Internet commentary takes into account. They include everything from industrial base and workforce considerations to procurement policy and recent government experience in other areas of space acquisition.

Budget is policy

The introductory speaker was the Director of the Space Policy Institute, Scott Pace. (Pace’s charts can be accessed here.) Pace began by noting that there are currently multiple policy reviews underway within the executive branch on aspects of American space policy. Of course, the White House is, in collaboration with NASA, determining how to respond to the Augustine committee. But the National Security Council is also leading a Presidential Study Directive review of the American national space policy. In addition, the Department of Defense is also conducting a congressionally-mandated “Space Posture Review.”

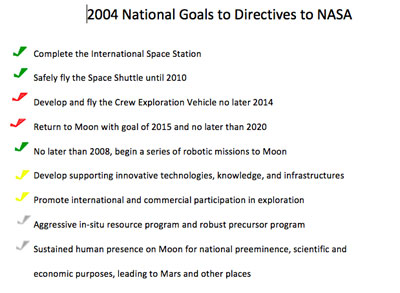

According to Pace, the presidential policy established in early 2004 gave nine directives to NASA. The agency has achieved, or is close to achieving, several of these. But it is clearly not going to fulfill several others unless substantial changes are made to the program, and additional money is provided.

|

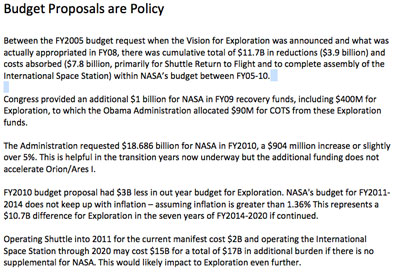

Pace also talked about something that he often stressed to his students: “budget is policy.” Although the Bush administration had outlined a new space policy in early 2004, it had pursued what was in many ways a different policy in its subsequent budgets, which continually reduced the money available to the space agency below that which the administration had originally promised to provide. This made it impossible for NASA to plan a program based upon budget promises that were later reneged.

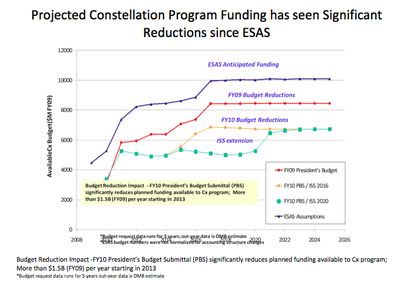

Pace showed a graph presented by Sally Ride at one of the committee’s hearings that illustrated the different funding levels for the Constellation program that were promised to NASA over the past five years. As time went on, less and less money was made available to the program. The different levels fanned out, always curving down. He said that within NASA this was referred to as “the sea-fan of death.” (Author’s note: one thing that has been ignored by much of the media coverage and commentary concerning the Augustine Committee’s recommendation of an additional $3 billion per year for NASA is that this is essentially the money that was removed from the budget, combined with that required to maintain the ISS to 2020.)

|

According to Pace, the retirement of the Shuttle and the development of Constellation is being handled by NASA in a fundamentally different way than the transition from Apollo to Shuttle, when massive numbers of trained aerospace workers were fired and it was literally true that aerospace engineers were driving taxicabs. In contrast, Pace explained that this time NASA is trying “to treat the transition as an integrated whole.” The agency is trying to avoid completely losing knowledge and skills in its workforce by transitioning employees from Shuttle to the new program with minimal disruption.

Pace then displayed a detailed listing of all of the budget cuts and hidden takes from NASA over the past five years. These included everything from money that was promised in the out-year budgeting plans upon which program decisions were based, to inflation and to actual cuts in the NASA budget. By his calculation, NASA had taken over $42 billion in hits against its “nominal program.”

He then outlined what he considers to be the underlying policy issues. The first question is if there needs to be government-supplied human access to space.

| By Pace’s calculation, NASA had taken over $42 billion in hits against its “nominal program.” |

Another policy question is the role of NASA. Should the agency have the ability to do systems engineering itself, or should the agency rely solely on contractors to provide this capability? Pace said that the United States has “gotten comfortable” with US astronauts flying on Russian vehicles and asked what is needed for the government to get comfortable with astronauts flying on commercial vehicles.

|

In a partial answer to one of his questions, Pace noted that during the 1990s, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) leadership made a decision to lose its system engineering capabilities and rely heavily on contractors. This was “not a good experience,” Pace said. (Author’s note: although he did not mention it, one well-known NRO procurement disaster that has been blamed at least partially on poor systems engineering experience and oversight within the NRO was the Future Imagery Architecture reconnaissance satellite program.)

Pace finished with what he considers to be the biggest policy question: why do we have a human space program? What are we doing this for? He said that one of the questions he poses to his students is: is there anything economically advantageous for humans to do in space? If not, is there a future for humans beyond the Earth at all?

The dangers of a camel

The next speaker was General Lester Lyles (ret.), who served as a member of the Augustine Committee. Lyles recounted that the committee had to operate under a number of limitations, including the short timeframe and the requirements of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA). FACA required that the committee hold only public forums and could not deliberate behind closed doors. The committee was also not allowed to make recommendations, only to develop options.

Lyles noted that he had served on previous boards and commissions that prepared him for this and gave him insight into the committee’s issues. He had chaired the NASA Advisory Council’s aeronautics committee, and believed that aeronautics was still an important national priority. He had also served on a recent national security space committee, and a National Research Council study on the rationales and goals of the civilian space program. Lyles said that there were common themes relevant to all of these committees: first was “the importance of the space program to every aspect of life.” This included national security, science, economics, national prestige, and international relations. Second was a concern about the United States losing its edge in space.

According to Lyles, the charge for the committee established a number of issues that they were supposed to address. This included whether heavy-lift was necessary for human space exploration. Another issue was how to achieve human access to low Earth orbit. They were also told to develop at least two options that stayed within the FY2010 budget out to FY2020.

Lyles said that in the course of their deliberations, the committee developed some of its own goals. “Safety and reliability was a major goal that we kept in front of us,” he said. They also were concerned with the affordability and sustainability of the overall program. When asked what he meant about sustainability, Lyles said that he was referring to political sustainability.

To tackle such a big charge, the committee members divided up their tasks and formed subcommittees based upon each member’s areas of expertise. “There’s always a risk in doing that,” Lyles said. “You might get a camel.”

Lyles said that the committee’s final report would hopefully be delivered by the end of the month (note: the final report’s release has been delayed). In response to a question he said that it would contain a lot more detailed analysis supporting the conclusions already released. He had just seen chapter 6 that morning and said that “It will be an engineer’s nightmare… or a dream.”

| A guiding principle for the committee’s findings that is in its report, although not necessarily in these same words: “Great nations do great things, and this is a task—human spaceflight—worthy of a great nation.” |

After numerous data-gathering sessions and deliberations, Lyles said, the committee reached a number of conclusions. One was the importance of venturing beyond low Earth orbit. Another was that heavy-lift capability is necessary for the task. He said that the committee also determined that a separate technology development program was necessary. Currently, all of NASA’s technology development is focused towards specific missions, not for a range of possible future missions. In response to a question about how to maintain a separate technology development line—which tends to be one of the first things raided when budgets get tight—Lyles said that it would be up to Congress to protect it.

Lyles said that there was a guiding principle for the committee’s findings that is in its report, although not necessarily in these same words: “Great nations do great things, and this is a task—human spaceflight—worthy of a great nation.”

The possibility of a horrible mistake

The next speaker was Tom Young, former CEO of Martin-Marietta and himself the chair of numerous high-level review commissions, particularly of military and intelligence space programs.

Young said that the Augustine Committee had concluded that “the current program is not executable with the current budget.” He added that this was not really a surprise. “A lot of us knew that, but we needed some group to say it,” he said. Another conclusion of the committee was that there is “no credible human exploration program executable with the current budget.”

There are two findings in the report that Young said he hopes are further developed. One concerns what to do with the International Space Station beyond 2015. He hopes that this subject is given a lot of thought. He said that right now the science conducted on ISS is not sufficient to justify the costs. The other aspect that he hopes receives greater attention is the committee’s endorsement of greater international cooperation in the program.

Young said that he thinks that the ISS should be devoted to better understanding long-duration human spaceflight, but added that “The centrifuge, that no longer exists, is critical to that effort.”

Young then turned to what he considered to be an area where he disagreed with the committee. “My personal belief is that today there is no demonstrated mature commercial human spaceflight capability.” He put emphasis on “demonstrated.” Right now, all of the efforts falling under the rubric of “commercial” were either suborbital space tourism, or cargo. Human orbital spaceflight, Young said, is a substantially more difficult proposition. “I hope it happens, I support it, I applaud it,” Young said, “but I would not build a program around it.”

Once again, NASA is trying to put ten pounds in a five-pound bag. “We’ve tried that experiment before,” he added.

Young also warned that in order for NASA to be a smart buyer and to ensure success, the agency needed in-house systems engineering talent. Echoing Scott Pace’s earlier comments, he said that during the 1990s the United States engaged in a number of “acquisition reforms,” including the Air Force’s reduction of oversight of contractor operation of launch vehicles like the Titan IV as well as some of the aspects of NASA’s “faster, better, cheaper” program. (Author’s note: Young was clear that he was not criticizing faster, better, cheaper in its entirety.) “We just fired all of the experienced people,” Young said, and adopted a policy that “government would sit in the back of the room” and let the contractors run the show. “That was a horrible mistake. The net result of that experiment was $11.2 billion in failures. We tried that experiment, it was a horrible failure.”

Young connected those past efforts at acquisition reform to what he considers the current claims that commercial crew is the way to substantially decrease costs to the government. “There is no magic,” he warned. “When someone comes along and says ‘I’ve got this new magic solution,’ my advice is to run for the hills.”

Young took several questions that were focused upon his remarks about the lack of a credible commercial crew-to-orbit industry. How can such an industry become credible without government supporting it? “You really have to be careful about what you mean by ‘commercial’,” Young replied. “You cannot have government provide 100% of the funding and do no close monitoring.” The only way to do it is to put private money at risk. “The private sector invests in providing a service that somebody comes along and buys. I don’t see an industry that is investing the capital that is necessary, and to the extent. I’m also skeptical of providers where there is only one market.”

| “There is no magic,” Young warned. “When someone comes along and says ‘I’ve got this new magic solution,’ my advice is to run for the hills.” |

Young finished by saying that if he could offer any advice to the people in the White House currently considering what to do about the future American human spaceflight program, it was to “treat it as a policy issue, not a budget one.” He noted that when people look back on the twentieth century, one of the great events they see on the American scorecard is the Moon landings. That was a policy decision, not a budget one.

Young joked that if he knew where the Obama administration officials were discussing the future of human spaceflight, he would sneak into the room and tack a sign up on the wall repeating what General Lyles had said before him: “Great nations do great things.” Although he did not advocate a return to Apollo, Young said that addressing every question in terms of annual budget decisions was ultimately a recipe for continued failure. For future generations looking backward at this time “I think it would be a sad thing if on our scorecard was ‘we saved $3 billion a year’.”

Policy decisions vs. budgetary decisions

Doug Stanley is currently on the faculty of Georgia Tech, but previously worked at NASA and Orbital Sciences Corporation. (His presentation materials can be downloaded here.) Stanley led NASA’s Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS) that developed the agency’s plans for returning humans to the Moon.

Stanley noted that numerous policy and budget decisions had led to significant under-funding of the Constellation program. This included two continuing resolutions in Congress and other cuts. He displayed a chart indicating the budget line that ESAS had been told to plan for compared to what it was actually now going to get. He explained that buried in these budget planning charts were many assumptions about arcane subjects like the rate of inflation. Arguments over fractions of a percentage point when calculating the inflation rate over the lifetime of a program might seem trivial, but could actually mean a difference of billions of dollars.

According to Stanley, the architecture that emerged from ESAS was the result of a number of assumptions they made when they started their evaluation. Had some of those assumptions been different, their architectural design would have been substantially different. As an example, if the Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV, now named Orion) had not been required to go to the International Space Station, then they would have produced a requirement for only a single launch vehicle rather than the Ares 1 and Ares 5 combination that they ultimately produced. On the other hand, if the requirement had only been for the CEV to go to the International Space Station, they would have selected an EELV (i.e. the Atlas or Delta). Stanley said that now that the assumptions have changed, it was entirely legitimate to question if NASA was developing the right architecture.

Stanley said that there are now some major questions that have to be answered about the human spaceflight program. The first is whether or not ISS should be extended to 2020. The second is if shuttle should be extended into 2011, as now seems likely, or beyond 2011. Another major question is whether or not the United States will pursue beyond-LEO missions and in what timeframe and what budget profile. Another question is the government’s policy toward commercial crew.

| Stanley said that now that the assumptions have changed, it was entirely legitimate to question if NASA was developing the right architecture. |

This last issue, Stanley said, “is more of a policy decision than a budgetary one.” The reason is that the marginal costs of flying additional Ares I rockets is not significantly greater than developing and maintaining two commercial providers. If the Obama administration chooses to do this, it will have to be for reasons other than saving money—i.e. a policy decision, echoing Tom Young’s closing comments.

The view from the Hill

After Stanley, the discussion turned to Capitol Hill and the next speaker was J.T. Jezerski, the legislative director for Republican congressman Pete Olson of Texas. He joked that “In my NASA days, I was a ‘One-NASA, ten-healthy-centers’ guy, but now I’m here to talk about the Johnson Space Center.”

Jezerski said that Washington is “not unwilling to spend money” at the current time. He noted that NASA has bipartisan support in the Congress, but added that NASA also has bipartisan opposition. He noted that both liberals like Barney Frank and conservative Republicans view NASA as a luxury.

The value of the Augustine Committee, according to Jezerski, was that it focused attention. “The best contribution has been to provide a number that we can all hang our hat on.”

Jezerski referred to the rather hostile reception that the committee report received during a recent hearing in front of the House Science and Technology Committee. He said that there was a great deal of frustration in Congress because they did not see a strong Augustine Committee endorsement of a program that Congress itself had already endorsed.

Jezerski also explained some of the changes in the political terrain as it pertains to NASA. The recent turnover during last year’s election had not been good to the agency. He noted that the agency’s three main centers are now represented by four freshmen congressmen whereas previously they had experienced legislators. In addition, they also lost important appropriator seats. All of this undercuts the agency’s ability to get a sympathetic audience on the Hill.

He finished by mentioning a recent editorial titled “U.S. Cannot Responsibly Avoid a Significant Investment in its Space Program” that appeared in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. He suggested that supporters send that editorial to the White House.