How competitive is commercial launch?by Jeff Foust

|

| “Current US policies can and should be reformed to encourage competition and diversification for satellite operators, consistent with US national security considerations,” said Warner. |

The move comes at a time of growing momentum to reform the nation’s export control regulations, which were tightened in that 1999 law specified in the presidential determination by placing commercial satellites and their components on the US Munitions List. That move made it more difficult for US manufacturers to sell their spacecraft, or spacecraft components, to customers outside the US, and has been a sore point for the domestic satellite industry for the last decade. Whether this move by the Obama Administration is a first step towards greater export control reform—or a move that could generate a backlash against further changes—remains unclear.

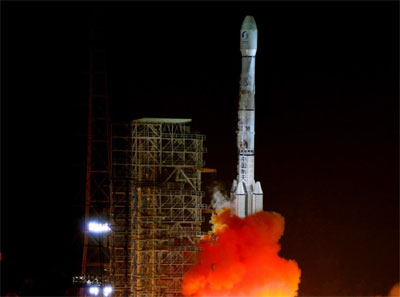

At the same time, commercial satellite operators have been pushing for broader policy changes that would open up the market for commercial launches. Last month four of the largest operators—EchoStar, Intelsat, SES, and Telesat—announced the formation of the “Coalition for Competitive Launches”. The organization has two broad goals: pushing the United Launch Alliance (ULA), the Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture that manufactures the EELV family of vehicles, Atlas and Delta, to make those vehicles more commercially available; and changing policy to permit the launches of US-manufactured satellites (or satellites with US-manufactured components) on Chinese vehicles.

Supporting the coalition is retired senator John Warner, a Republican from Virginia whose 30 years in the Senate included several as chairman of the Armed Services Committee. The coalition, he said in a statement announcing its formation, “seeks to increase launch vehicle options that could ultimately lower costs for users of communications satellites, while addressing the concerns of the US Government regarding the potential transfer of sensitive satellite technology.”

“We call on the Defense Department, the State Department and other national security arms of our Executive Branch to take a new look at our country’s launch vehicle capabilities and relevant export control policies,” Warner continued. “Current US policies can and should be reformed to encourage competition and diversification for satellite operators, consistent with US national security considerations.”

It’s no surprise that satellite operators have sought to increase competition in the launch market to blunt a rise in launch prices in recent years. At the Satellite 2009 conference in Washington in March, executives of major operators expressed interest in both commercial Atlas and Delta launches as well as increased use of Chinese vehicles (see “Satellites, launches, and the recession”, The Space Review, March 30, 2009). Their interest in launch alternatives has grown after Sea Launch, one of the major commercial launch providers, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in June.

The commercial launch industry, though, maintains that there is ample capacity in the market today to support existing and projected demand. During a session at the AIAA Space 2009 in Pasadena, California, on September 17—the day after the announcement of the Coalition for Competitive Launches—launch industry officials reiterated their belief that commercial customers didn’t need to reach out to either or the Chinese or EELVs to secure their business.

Clay Mowry, president of Arianespace Inc., noted that his company can launch about seven Ariane 5 vehicles a year, each carrying two commercial satellites. His biggest competitor, International Launch Services (ILS), can do up to eight Proton launches a year. Land Launch—which uses a modified version of Sea Launch’s Zenit-3SL launched from Baikonur—and Soyuz can also launch several more smaller commercial satellites a year. “There’s demand—orders—for 20 new satellites [a year] and there’s capability to launch 27,” he said. “So we think we’re pretty much at the right size.”

That explains, he added, why Sea Launch, which could launch up to six satellites a year, filed for Chapter 11, especially since it didn’t have the government business and support of its competitors. “Without that kind of capability in place, it’s very hard to make a go of it in the commercial business,” he said.

| “The global launch business is not a normally functioning market. Everybody is subsidized,” Aldrin noted. |

There’s also the question of how interested and capable ULA is in taking on additional commercial business. Andrew Aldrin, director of business development for ULA, noted at the Space 2009 session that the Atlas 5 manifest was “nose-to-tail” through 2010, with no room to squeeze in additional launches. “There are things we can do to accelerate this,” he said, such as moving the average time between launches down from 60 days to 45. Nearly that entire manifest, other than a commercial Intelsat launch scheduled for next month, is for US government customers.

Aldrin noted that ULA is interested in supporting Boeing and Lockheed in the commercial launch market (ULA itself does not sell commercial launches, leaving that to the marketing arms of its two owners, Boeing Launch Services and Lockheed Martin Commercial Launch Services). Additional business, he said, would help spread out costs and enable ULA to make larger buys of components that further reduce costs—if there are customers for it.

“If we increased out manpower levels we could increase the launch rate,” he said. Additional infrastructure, such as another vertical integration facility for the Atlas 5, could do the same, he noted. “But there aren’t the launches out there.”

Antonio Elias, executive vice president of Orbital Sciences Corporation, a company that builds but doesn’t launch commercial GEO communications satellites, took a different viewpoint in the panel session, challenging the claims by others that there was an overcapacity in the launch market. “We’ve seen cases where our customers, the GEO commercial satellite operators, had trouble manifesting and remanifesting their payloads,” he said, particularly in the wake of launch failures or manufacturing delays.

Gwynne Shotwell, president of SpaceX, which is moving to compete head-to-head in the commercial launch market with Arianespace, ILS, and others, tried to split the difference between the views of current launch providers and launch customers. “I think there is overcapacity of expensive launch,” she said. “There is not enough capacity of low-cost launch.”

What specific steps the Coalition for Competitive Launches plans to take to try and make the launch market more competitive remain unknown: the group has been quiet in the month since it announced its formation. Warner has had little to say publicly on the matter, including in a Washington Examiner column earlier this month that pointed out that, as a senator, he voted for the bill that tightened the export restrictions the coalition is now trying to loosen.

Launch providers aren’t opposed to competition, the Space 2009 panelists noted, but caution that the market is not a typical, ordinary market. “The global launch business is not a normally functioning market. Everybody is subsidized,” Aldrin noted.

“I think competition is a good thing. I think we’ll all learn how to do things smarter and better when there’s really competition in the marketplace from a price perspective,” said Shotwell. “I do agree that this market is currently a fragile market—it’s not really driven in any normal way—but wouldn’t it be great if it were, and the best rocket with the lowest price wins?”