Just how soft is NASA’s soft power going to be?by Taylor Dinerman

|

| If China does in fact enter into a long-term relationship with NASA, this could be a good thing, but only if the US negotiates from a position of strength. |

The Augustine committee report states: “If the U.S. is willing to lead a global program of exploration, sharing both the burdens and the benefits of space exploration in a meaningful way, significant benefits could follow. Actively engaging international partners in a manner adapted to today’s multipolar world could strengthen geopolitical relationships, leverage global financial and technological resources, and enhance the exploration enterprise.” Nice words, but not a very substantial basis for policy.

The Bush Administration’s approach was arrogant. They said, in effect, “We’re going to the Moon, and eventually to Mars, if you want to come along, fine. Don’t get in the way and pull your own weight.” This may have disturbed some foreign space policymakers, but it at least had the virtue of being clear and reflecting financial and technical realities. Unless there is a radical change in both US policy and in the shape of the world’s economy these realities are not going to change for at least the foreseeable future; say twenty years.

As of now the Obama Administration is still making up its mind what to do, where it wants to go, and above all what it wants to spend. There is at least a possibility that the next NASA budget will simply reflect the status quo. If there is a large cut to the budget then the plans may change, but it will be difficult to durably change the overall direction of the program. At some point, a little more than a decade from now, America will send humans beyond low Earth orbit.

Atmospherics, however, are also important. If the US is seen as meekly asking the rest of the world to please support the goals and ambitions of the exploration program, it will be treated with contempt. This will not only make it exceptionally difficult to come up with acceptable international agreements, but it will almost certainly ensure that the next Congress or the next administration will seek to overturn any unfair, unequal, or humiliating deals made by the current leadership.

NASA’s experience with major international exploration agreements has been mixed. The Apollo-Soyuz deal put together by Nixon and Brezhnev in 1972 and flown in 1975 was a bit of propaganda for the idea of “detente”. As Walter McDougall put it in his authoritative …the Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age, “it gave Soviet technicians the chance to traipse through US space facilities and flight operations firsthand.” That’s something the Chinese can do today simply by going on the Internet.

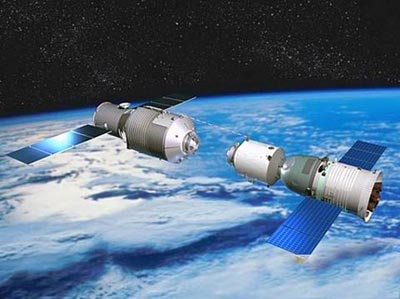

The Apollo-Soyuz flight was a dead end. Twenty years later, in February 1995, the Shuttle flew its first mission to Russia’s Mir space station. This was an early step in NASA’s second great international program, the International Space Station (ISS), and in spite of everything it has been a technological success. It has taught NASA and its partners invaluable lessons in building and maintaining large structures in space. The Clinton Administration, which created the program, and the George W. Bush administration, which largely built and paid for it, made sure that it was recognized as a US-led program.

Neither of these projects represents a good or accurate model for the current situation. With Apollo-Soyuz the hardware already existed, so modifying it for the “Handshake in Space” that was intended to symbolize the end of the US-Soviet confrontation was not that difficult. The ISS project was based on previous work done by NASA on Space Station Freedom and above all on the need for Clinton to show some magnanimity towards the Russians. Today Washington’s political motivation for a US-Chinese joint space project is pretty murky.

The Chinese have publicly laid out a path that does not require any international cooperation. They could change their plans, but this might upset delicate internal political or industrial arrangements that we know nothing about. There has been a lot of speculation about the exact motives that drive their human exploration program, but few hard facts have emerged.

| If the US presents itself as too eager for partnership agreements or too weak to explore the solar system without assistance, then the world and the American people will only see softness. |

On the other hand, we know that the Obama Administration and Congress are chock-a-block full of motivations, many of them contradictory or confused, but all of them expressed with passion. There are political motivations: after all, Florida, Texas, and California are all big voter-rich states. There are questions of prestige and international power. There are industrial, scientific, and technological reasons why leaders in Washington think that this is important. There is a strong desire on the part of both parties to use NASA’s accomplishments as a way to inspire kids to study science and engineering.

In all of NASA’s programs, ever since the Eisenhower days, there has been an element of “soft power”. Some administrations have used it more effectively than others, but it has always been there. Yet this kind of power is only a tool, not a goal in itself. If the US presents itself as too eager for partnership agreements or too weak to explore the solar system without assistance, then the world and the American people will only see softness.