Responsible launching: space security, technology, and emerging space statesby Ben Baseley-Walker

|

| A cause for concern lies in the reality that states may cause damage to assets or the space environment—not with hostile intent, but through a lack of basic technical and operational competence. |

While the space environment has experienced many shifts over the last two decades, perhaps the most noticeable has been the sharp increase in the number of nations operating satellites. From the space security perspective, this is cause for both optimism and disquiet in equal measure. Hope can be derived from the fact that, as more and more nations come to rely on space systems and the services that they provide, their desire to protect those assets and safeguard their continued utility and that of the space environment increases.

This positive direction however, comes with its accompanying anxieties. Emerging space states tend to operate at a lower level of technology with less capacity and operational experience than states with established space programs. A cause for concern lies in the reality that states may cause damage to assets or the space environment—not with hostile intent, but through a lack of basic technical and operational competence. Irresponsible or incompetent action on orbit is of harm to all who operate space systems. While it seems fundamentally unfair, new states have less freedom of experimentation and trial by error than their predecessors, since the orbital environment just cannot sustain further misadventure.

Currently 41 countries operate satellites, with more being added every year [1]. Of these 41 almost all have the ability to identify the orbital position of their own satellite, yet very few have the access to, or the technical ability to interpret, the locations of other objects in space. The number of actors that have the technical ability to identify the position of their space systems in relation to other space objects is low.

So how can we hope to ensure that new space players act responsibly? Perhaps one method would be to look at a key component of undertaking space activity: one has to reach space in the first place. Further, only eight states (Russia, the United States, China, France (Europe), India, Japan, Israel and Iran as of February 2010) have indigenous launch capability, a number that is still small. This is mostly because developing the technology and hardware to get to space is neither easy nor cheap, as the ill-fated space launch programs of States like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Brazil have shown.

In effect, this means that those eight states control who can place objects in space. Of these eight states with launch capability, only six of them have launched satellites of other countries. Those states that have put in the money and effort to develop launch capability are also more invested than others in their ownership of space systems and their reliance on space resources. A satellite collision in Sun-synchronous orbit would create debris that could affect the operations of the approximately 250 satellites located in that orbit, the vast majority of which are owned by the eight states with launch capability [1]. It is therefore in the interests of all launching states to ensure that only those actors with sufficient technical capacity to operate safely in space have access to their launch services.

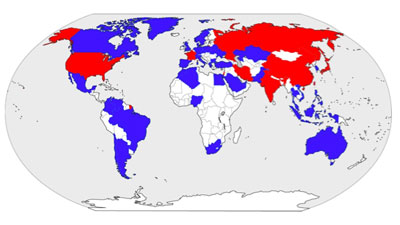

Launching states (red) and spacefaring states (blue). This map shows current States capable of orbital launch and those States that have operated or are operating satellites of their own. States with the capability to launch payloads into orbit include the United States, Russia, France (as majority shareholder of Arianespace, which also launches payloads for the European Space Agency), China, Japan, India, Israel, and Iran. States that have operated or are currently operating satellites include the Soviet Union (1957), United States (1958), the United Kingdom (1962), Canada (1962), Italy (1964), France (1965), Australia (1967), Germany (1969), Japan (1970), China (1970), Poland (1973), Netherlands (1974), Spain (1974), India (1975), Indonesia (1976), Czechoslovakia (1978), Bulgaria (1981), Brazil (1985), Mexico (1985), Sweden (1986), Israel (1988), Luxembourg (1988), Argentina (1990), Pakistan (1990), Russia (1992), South Korea (1992), Portugal (1993), Thailand (1993), Turkey (1994), Ukraine (1995), Chile (1995), Malaysia (1996), Norway (1997), Philippines (1997), Egypt (1998), Singapore (1998), Denmark (1999), South Africa (1999), Saudi Arabia (2000), United Arab Emirates (2000), Morocco (2001), Algeria (2002), Greece (2003), Nigeria (2003), Iran (2005), Kazakhstan (2006), Belarus (2006), Colombia (2007), Vietnam (2008), Venezuela (2008), Switzerland (2009). Note the increasing number of states in recent years. Map courtesy of Secure World Foundation. |

As an intellectual exercise, one possible way of achieving this desired effect is to look at the value of developing some form of agreement between launching states to only launch space systems of states that meet pre-determined minimum technical and operational competency requirements. The outcomes of building agreement on minimum technical and operational competences would be twofold: first, it would prevent ill-equipped actors from participating in space and, therefore, protect the space environment and the assets of others; second, it would establish the basis for the future of norms of responsible behavior in space. Such an agreement, were it to be developed, would take the form of a non-binding “gentlemen’s agreement” in the model of the IADC guidelines [2]. Moves towards domestication of any consensus could lay the groundwork for subsequent state-by-state regulation of foreign customers in governmental and commercial launch markets.

| The thinking behind this concept is not focused on freezing out new entrants to the space arena nor in creating a space cartel. Rather, it is focused on moving towards ensuring that in the long term all actors will be able to safely take advantage of the tremendous resources that space has to offer. |

Hypothetically, to put such a concept into practice, first, individual states, and most pertinently launching states, must determine what they consider minimum standards of technical competence to operate in space. While this might not be easy, given that the aim is to limit the access of dangerously incompetent actors to space, elements such as a basic ability to interpret space situational data, methodologies for collision avoidance, and signature of and adherence to the principles of the major international space conventions would seem to be a starting point. From these basics, criteria could be developed to analyze the capacity of non-launching states to safely operate space systems.

It is worth mentioning that the thinking behind this concept is not focused on freezing out new entrants to the space arena nor in creating a space cartel. Rather, it is focused on moving towards ensuring that in the long term all actors will be able to safely take advantage of the tremendous resources that space has to offer. It is important to recognize that any such regulation would need to be complemented by technical capacity-building in order to ensure that aspiring space states can work towards achieving basic technical competence in their space activities.

Such an agreement, while only a small step in the greater scheme of enhanced space security, might open the door to further progress. The coupling of technical capacity building with the laying down of a voluntary framework that encourages safe space operations in new space states would seem to be to the demonstrable gain of all major spacefaring nations and the international community at large. Given the leverage that states with launch capability have over those space states that do not have such capability, developing universal conditions for non-launching players may be achievable. While such an agreement may not actually be politically feasible in reality, thinking about this issue in such terms gives rise to the conversation on what exactly we consider to be the standards for competence in entry-level space activities. Elucidating such standards can only assist in increasing the predictability and stability of international interactions on space activities.

References

[1] Union of Concerned Scientists satellite database, accessed 02/20/10.

[2] UN Guidelines on Debris Mitigation, previously the “IADC Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines,” IADC-02-01, Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, 15 October 2002.