Human spaceflight: diversify the portfolioby S. Alan Stern

|

| What we need now is more than just a flexible path. We need parallel paths. |

Instead, human spaceflight in the United States has struggled just to keep its sole domestic transportation system, the Space Shuttle, flying a few times per year, and to complete the assembly of its sole destination—the International Space Station. And new programs, with names like Orient Express, SEI, Orbital Space Plane, and now Orion/Ares, in every case became politically or fiscally unsustainable, yielding only hallucinations for space exploration, rather than the real thing. This is something we must change if the United States is to lead in space.

One common characteristic of human spaceflight efforts in the US is that they have consistently revolved around a monolithic architecture-destination combination that required the efforts of many tens of thousands of individuals and virtually the entirety of NASA’s human spaceflight development budget.

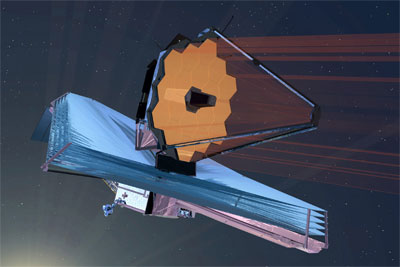

By contrast, in NASA’s science program, which I formerly directed, dozens and dozens of concurrent space flight projects are always in development, from brief suborbital missions, to small Earth orbiters, to small, medium, and large-scale planetary missions, to vast multi-billion dollar efforts like Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope that require thousands of individuals to develop.

The diversity of NASA’s science mission portfolio is one of its great strengths, for no single mission, no individual development, no single charge number, and no single launch risks the fate of the entire program. After all, it’s no secret that if you only own one stock, you probably deserve what you get.

This diversity of science mission efforts, just like the diversity in other forms of aerospace development—from airliners to missiles to combat aircraft to transports—is a trait that civil human spaceflight could well benefit from.

Fortunately in the Obama Administration’s vision for NASA, we already see the seeds of a diversified portfolio for human spaceflight. In its fiscal year 2011 NASA budget request, the administration requests funds to use multiple human-carrying suborbital vehicle designs to conduct research and education missions, and to initiate two separate new human-carrying systems to transport crew to the International Space Station.

Multi-pronged of this sort efforts promote competition, drive innovation and design diversity, and give the government valuable cost control options that monolithic (single-legged) transportation access does not. Multiple efforts also provide a kind of robustness in the event of accidents that domestic human spaceflight has never before enjoyed.

The Administration is to be commended for this fresh and promising approach, and Congress should endorse it in the authorizations and appropriation processes. Could that same approach be further extended, to help us again realize human exploration of the solar system?

| It is time to reinvent human space exploration, to make it simultaneously affordable, sustainable, exciting, and robust. |

There are no laws of man or physics that require human exploration systems to cost tens of billions of dollars and take multiple decades to field. Indeed, there is now ample empirical evidence that old-style, Apollo-like development practices today produce more commotion than forward motion, and have only stymied the pace and achievement of human space exploration.

What we need now is more than just a flexible path. We need parallel paths.

To be more specific, we need a suite of lean human space exploration system development efforts, each perhaps fielded by different NASA centers, in analogy to how we implement robotic spaceflight. These new human exploration efforts should be aimed at putting in place simultaneous lunar and asteroid exploration, high earth orbit and Lagrange point servicing, and perhaps the first forays to the planets.

Of key importance to successfully exploiting this approach will be the recognition that these new systems—developed in most cases via non-traditional “NewSpace” economic practices—cost pennies to dimes on the dollar compared to the old-style “so big they always fail” human spaceflight efforts. This is how Burt Rutan’s Scaled Composites invented and fielded a fledgling human spaceflight capability for many times less than NASA expended on Space Shuttle brakes alone.

Lowering costs through true competition and the realization that projects can be cancelled is fundamental: for it is only the combination of a multiplicity of efforts and breakthrough price points that makes a diversified human spaceflight portfolio viable.

So let’s incent industry to produce safe systems for human exploration inexpensive enough for NASA to afford multiple parallel efforts. And let’s ask how, more than 40 years after Apollo—as far in Apollo’s future as Charles Lindbergh was in its past—American ingenuity can produce a lunar return by Americans for a development cost of $3–5 billion, a high orbit satellite servicing capability for still less, and a first mission to a near Earth asteroid that costs no more than ten times what a decade-long robotic mission to Pluto does—say for $7–8 billion.

Yes, the developments that result may be limited in their capability compared to what $100-billion development efforts might promise, but expensive, monolithic development efforts have been singularly unproductive in delivering any actual exploration.

It is time to reinvent human space exploration, to make it simultaneously affordable, sustainable, exciting, and robust. It may be hard, but it is time to find a new way forward that can serve the future, rather than the past.

So let’s diversify our human spaceflight portfolio in the United States, let’s reinvent how we do things, let’s turn some heads, and let’s make history and lead again, and again, and again.