Secrets of the red planetby Dwayne A. Day

|

| For years, articles about the film questioned whether or not NASA provided any equipment for a movie that clearly painted the agency in a bad light. NASA officials reportedly denied that they had provided any assistance. |

Because of this, one of the more head-scratching examples of NASA’s involvement in a film is the 1978 movie Capricorn One. Capricorn One is a classic post-Watergate conspiracy thriller. The plot is simple: NASA fakes a Mars landing. The three astronauts who were supposed to go on the mission are instead held captive. They escape, and are pursued across the desert and killed one by one before a crusading reporter (à la Bob Woodward) shows up to rescue the last survivor. Capricorn One is not a great film, but as a conspiracy thriller it’s pretty good. The story is tight, the suspense builds well, and the film reaches its climax with a great aerial chase sequence involving a biplane and a couple of Army helicopters over the Mojave Desert—not far from where SpaceShipTwo is currently taking to the air. In the film, NASA is clearly evil. After all, the NASA administrator is behind the conspiracy, and even approves the astronauts’ murders.

During a sequence in the middle of the film the astronauts are shown with a lunar module (standing in as a Mars lander) and there’s also an Apollo command module visible in some shots. The lunar module featured prominently in the film’s trailer. For years, articles about the film questioned whether or not NASA provided any equipment for a movie that clearly painted the agency in a bad light. NASA officials reportedly denied that they had provided any assistance.

But an amusing article by film historian Frederick C. Szebin, “The Making of Capricorn One,” explains what happened, and makes clear that the film did indeed use some leftover Apollo equipment loaned by NASA. The article is printed in the current issue of Filmfax magazine, but has apparently been available online for a decade at the website mania.com (in a somewhat difficult to read format).

Szebin interviewed Capricorn One’s producer Paul Lazarus, who had previously produced Michael Crichton’s Westworld and a 1976 sequel, Futureworld, which had involved some NASA cooperation. Lazarus got involved because he was friends with Peter Hyams, who wrote the initial Capricorn One script, and who wanted to direct the movie. Hyams had recently directed an embarrassing flop, and both men worried that Hyams’ career was over. Capricorn One proved to be the movie that saved it, because Hyams brought it in on-budget and it made a decent amount at the box office. According to film historian Szebin:

The key to getting such a film made within the budget available was to have NASA’s cooperation, a situation Lazarus had enjoyed on Futureworld. A stunt-heavy picture, Capricorn One could only gain from the space administration’s assistance, but the very nature of the story—NASA killing its own to keep a secret—caused Lazarus to despair of any further help from the organization.

“This is a highly unlikely film to get NASA cooperation, because they are the bad guys in the movie,” says Lazarus. “But I called my contact at the NASA Clear Lake facility [i.e. the Johnson Space Center], and he said he would have to see a script. I said to Peter, ‘We’re dead.’ I sent the script and my contact said, ‘Oh, it’s a good story! We’ll be happy to give you our prototype landing module.’ We didn’t have to build any of that! It came up from Orange County, California. In a sense, it’s tax-payer paid for, but anybody who’s been around the government knows that if it’s not something they like, you’re not going to get cooperation.”

“We had untold savings, not to mention authenticity, to get those capsules and other materials from NASA,” Lazarus continues. “Much after the fact, I said to someone at NASA, ‘How could you possibly have approved that script?’ He said, ‘If it had gone to Washington, you would have been finished, but because we liked working with you on Futureworld, I took it upon myself to give cooperation.’ I said, ‘We’re really grateful and surprised.’ He said, ‘I thought you might be.’”

| ‘If it had gone to Washington, you would have been finished, but because we liked working with you on Futureworld, I took it upon myself to give cooperation.’ |

Szebin’s article contains a number of humorous stories, including Lazarus’ interactions with Sir Lew Grade, who ran the ITC production company in England that had produced Space: 1999, and who raised much of the money for the film. Grade was a quirky character, but far easier to work with than either Lazarus or Hyams expected, or were used to. They had to nix one of his ideas, to use the Space: 1999 sets (the whole point was that the astronauts never even went into space, so the sets weren’t needed, they told him), but he did not interfere in the production, which was virtually unheard of. They did have to accept Grade’s decision to use television actor Telly Savalas in the role of the abrasive crop duster, Albain, even though Lazarus thought that Savalas’ reputation as detective Kojak was a joke. Grade told them that if they used Savalas, they would get half a million dollars from CBS. Savalas ended up turning in a performance that’s one of the best in the film. He was helped by some clever dialogue:

Robert Caulfield: Mr. Albain, how much do you charge to dust a field?

Albain: Twenty-five dollars.

Caulfield: I’d like to hire your plane.

Albain: That’ll be a hundred dollars.

Caulfield: You said you charged twenty-five.

Albain: Twenty-five dollars to dust a field, but you ain’t got no field because you ain’t no farmer, which means you ain’t poor and I think you’re a pervert!

Caulfield: Okay, one hundred.

Albain: One hundred and twenty-five.

Caulfield: What?

Albain: Because you said yes to a hundred too quick, which means you can afford a hundred and twenty-five.

Capricorn One benefited from the fact that Superman was behind schedule, leaving the studio with a lot of empty movie screens to fill in June 1978. The movie performed decently at the box office, until Grease and Animal House debuted and stole its momentum. It was the most successful independent film that year. According to Lazarus, the trade and local reviews of the film were pretty good, and he thought that the controversy—some reviewers claimed that it was absurd to portray a government conspiracy—only helped to sell tickets.

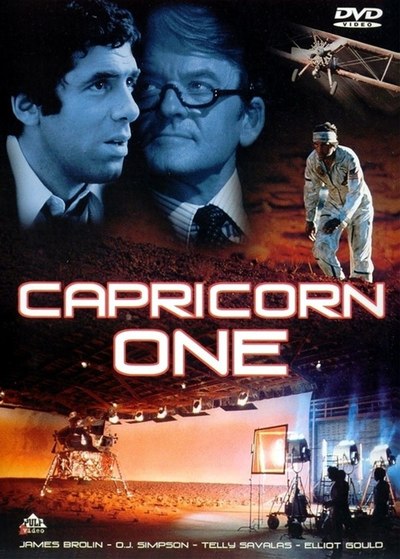

An updated Capricorn One poster used for the movie’s DVD release. |

Lazarus thought that the television commercials did a good job of selling the movie, but that the print ad they developed for the film—depicting the lunar module that NASA had loaned them on the surface of Mars—did not. “Mars landing hoax” was a high concept idea, but a little too difficult to summarize in a single image. Considering the chase sequence is the highlight of the film, they could have mimicked the famous poster from Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, with an astronaut running from a helicopter instead of a biplane. A later DVD of the film did have some of those elements mixed into a montage.

In the late 1990s, the Fox network flirted with the idea of a Capricorn One television movie, but abandoned it. In 2007 various trade publications reported that a new version known as Capricorn Two was “in development,” as was another of Peter Hyams’ movies, Outland. (See “Little red lies”, The Space Review, February 19, 2007.) Supposedly a writer and director had been selected for the movie and they already had a script. Those reports resurfaced in 2008. But there’s still no evidence of progress. The film is apparently in “development hell,” which is an all-encompassing Hollywood term that usually means that somebody has a script, or at least a story, but is unable to find people with money willing to invest and turn it into a movie—no Sir Lew Grades to round up the cash. Hollywood is awash in remakes that have not done particularly well at the box office (i.e. The A-Team, Land of the Lost), and that doesn’t help. It has been over three decades, but Capricorn One could easily be brought up to date and improved. With NASA’s lunar plans now scuttled, it would be easy to tell a story about a fake space mission. But if the movie ever does get remade, you can bet that NASA won’t be involved.