Space budgets are made to be brokenby Todd Neff

|

| Space program budget-busting, though, is as old as the space program. |

The letter makes for familiar reading. A 2009 report to Congress by the Government Accountability Office found that 10 of 13 major civilian space programs were over budget and behind schedule. Among its conclusions: “[C]ommitments were made to achieving certain capabilities without knowing whether technologies and/or designs being pursued could really work as intended. Time and costs were consistently underestimated.”

It’s not just NASA. Military space programs such as NPOESS (a joint mission with NOAA, now broken into several pieces), the cancelled TSAT communications satellite program, and the woefully over-budget SBIRS missile-detection system have had similar problems. Christina Chaplain, the same GAO expert who addressed NASA mission budget issues in 2009, told lawmakers in March 2010, “A long-standing problem in DOD space acquisitions is that program and unit costs tend to go up significantly from initial cost estimates, while in some cases, the capability that was to be produced declines. This problem persists.”

Space program budget-busting, though, is as old as the space program. Take the example of Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp., the Colorado engineering firm known for its Hubble Space Telescope instruments and scientific spacecraft. I don’t mean to single out Ball Aerospace—this is a universal issue in the space business. But I wrote a book about the company and know it best.

In 1948, a small University of Colorado team told Air Force scientists that, for $64,000, they could build path-breaking space hardware to observe the sun from the nose of a rocket. And build it they did, though they came in roughly ten times over budget and years behind schedule.

In 1959, some of those same students, now working for what is now known as Ball Aerospace, told NASA they could build the first sun-observing satellites—three of them—for about $850,000. They built one, and delivered it more than a year late and for about triple that amount.

The Air Force and NASA stomached these overruns. As Nancy Grace Roman, who served as NASA’s astronomy chief in the early 1960s, told me, “We recognized that we were doing something new and we had to learn how to do it. You could try things, and if they didn’t work, you could try something else. I have in the past compared the beginning of the space program to a baby learning to walk. It falls down occasionally.”

| In the business of space, the passage of time and accumulation of experience pays few dividends in predictability. |

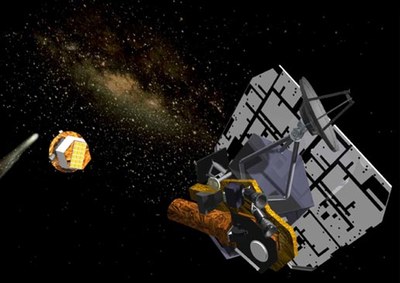

Some 40 years later, in 1998, Ball Aerospace proposed to NASA a $233-million spacecraft—actually, two spacecraft—to smash into the comet Tempel 1 and observe what pristine solar system building blocks their projectile unearthed. Deep Impact met its mark on July 4, 2005. The mission launched a year later than planned and cost a reported $333 million, which didn’t include the thousands of hours engineers toiled off the clock.

Deep Impact became the first spacecraft to touch a comet more than 43 years after the Orbiting Solar Observatory became the first to fix its gaze on the Sun from Earth orbit. The space program, far from a baby, had grown middle-aged. But the problems of budget and schedule have persisted.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Mars Science Laboratory (a.k.a. Curiosity), a rolling chemistry lab for the Red Planet, was slated to cost $1.63 billion (see “Mars Science Laboratory: the budgetary reasons behind its delay”, The Space Review, March 2, 2009). It will cost perhaps $2.3 billion when it launches in late 2011, two years behind schedule. And then there’s the James Webb Space Telescope, the budgetary scapegoat du jour.

What’s JWST prime contractor Northrop Grumman’s problem? I mean, all Grumman and mirror contractor Ball Aerospace have to do is fold an array of 18 hexagonal beryllium mirrors—each 1.3-meter section with actuators capable of adjusting it to an exactitude of less than 10 billionths of a meter—into the nose of an Ariane 5 rocket. And then fold five layers of Kapton sunshield, each as broad as a tennis court and as thin as a human hair and supported by “an extremely complex system of latches, tensioners, spreader bars and telescoping boom assemblies” into the same fairing.

“NASA and Northrop Grumman had to start from scratch and literally invent the techniques, materials, and mechanisms needed to do the job,” said Keith Parrish, Webb telescope Sunshield Manager at NASA Goddard, in a Northrop Grumman press release earlier this year.

In the business of space, the passage of time and accumulation of experience pays few dividends in predictability. The experience curve fails to descend. Costs spiral. Schedules spill over. Why?

| But I’ll bet that in 50 years, the American space enterprise, while doing incredible things, will still be delivering late and over budget. On the final frontier, humans will always be learning to walk. |

The space engineering bar inexorably rises. The digital revolution transformed spacecraft into soaring computers, exponentially increasing their capabilities—and complexity. Every scientific spacecraft is looking for something its predecessors failed to capture; the same holds true for many military spacecraft. It takes new technologies to plumb the unknown, or at the very least new combinations of proven technologies.

And let’s face it: we’re lousy at estimating. “Prediction is very hard, especially about the future,” as Yogi Berra put it. Jerry Chodil, the Ball Aerospace vice president who told NASA that Ball could do Deep Impact, described it to me like this: “I owned five acres out in Lafayette some years ago. I went to put up some fencing. Pretty straightforward, right? Well, it took me three times longer than I estimated.”

There are other factors at play. People in the space business tend to be optimistic about what they can accomplish. Proposal teams want to look like bargains to selection officials. And, as retired Ball engineer Tim Ostwald told me, “People don’t want to hear the truth. Especially managers and politicians do not want to hear the truth.”

Maybe some space engineering management revolution will prove me wrong. But I’ll bet that in 50 years, the American space enterprise, while doing incredible things, will still be delivering late and over budget. On the final frontier, humans will always be learning to walk.

Bibliography

JWST Independent Comprehensive Review Panel’s letter to NASA Administrator Charles Bolden (11/5/2010)

“NASA Projects Need More Disciplined Oversight and Management to Address Key Challenges,” Statement of Cristina Chaplain, GAO Director, Acquisition and Sourcing Management, before the Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics, Committee on Science and Technology, House of Representatives, March 5, 2009.

“Space Acquisitions: DOD Poised to Enhance Space Capabilities, but Persistent Challenges Remain in Developing Space Systems,” Statement of Cristina T. Chaplain, GAO Director, Acquisition and Sourcing Management, before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, March 10, 2010.