Reviews: Envisioning the universeby Jeff Foust

|

| The centerpiece of Sizing Up the Universe is a centerfold: a fold-out “Map of the Universe” about a meter long. |

In Sizing Up the Universe, Princeton University professors J. Richard Gott and Robert J. Vanderbei—the former an astronomer, the latter a visualization expert and avid amateur astronomer—take Adams’s challenge head-on by trying to explain just how big the universe is. The two start with an examination of apparent sizes of objects in the sky as seen from Earth, and from there go into an examination of ways to map the sky and measure distances to these objects, which then leads into a comparison of the absolute sizes of these objects. All this, as one might expect from a National Geographic book, is lavishly illustrated with many color images of planets, galaxies, nebulae, and more.

The centerpiece of Sizing Up the Universe is a centerfold: a fold-out “Map of the Universe” about a meter long. This map is a long, narrow projection, with distance from the Earth, on a logarithmic scale, along the long axis and celestial longitude on the narrow axis. The intention of such a map is to display identically objects of the same angular size as seen from Earth on the map, regardless of their actual physical dimensions; the Sun and the Moon, for example, would be the same size on the map because both are about half a degree across as seen from the Earth. (However, the Sun, Moon, and some other “famous objects” actually appear much larger on the map than they should, as a strict adherence to the map’s scale would render them too small to be visible. Clarity sometimes trumps accuracy.)

At times Gott and Vanderbei are in danger of getting carried away with the technical details of various map projections: in addition to the Map of the Universe (also called the Gott-Juric map), there’s an extended discussion of the gnomonic map of the night sky, where the celestial sphere is projected onto a cube; later, they show maps of the planets using different projections to reduce distortions or highlight certain features. Sometimes, simpler is better: among the most compelling illustrations in the book are images that compare the sizes of objects in the cosmos, particularly when something familiar and terrestrial is included. The massive size of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is made perfectly clear when shown in a two-page color image with Hurricane Katrina shown on the same scale—taking up a small part of one corner of the image.

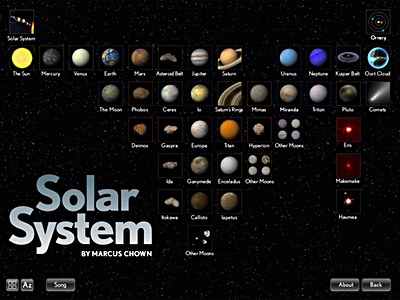

One of the limitations of Sizing Up the Universe—or any other print book—is inherent with the medium. Trying to represent a dynamic, three-dimensional universe into static two-dimensional pages will always be a struggle, making the book’s discussions of various map projections understandable. However, continuing advances in computers and multimedia technology allow for a different approach, as seen in Solar System for iPad. As the name suggests, it’s a publication designed specifically for Apple’s iPad tablet computer, putting the various planets, moons and other objects in the solar system literally at one’s fingertips.

|

The publishers of Solar System for iPad, Touch Press LLC, which also made the popular The Elements application that breathed new life into the fusty periodic table, similarly try to liven up the solar system. One can proceed linearly through the app, as in a book, starting from the introduction to the solar system and working outwards to comets and the Oort Cloud, or one can skip around, using either the home screen, where there are buttons for all the planets and other solar system objects, a slider at the bottom of the screen, or even an orrery that shows the motions of the planets around the Sun.

| Solar System for iPad is a close cousin of the multimedia astronomy CD-ROMs that became popular in the mid and late 1990s. |

The key strength of Solar System for iPad is its multimedia. The text, written by noted science writer Marcus Chown, is augmented by a wide range of images, movies, and animations. Images of planets and moons can be spun around with the flick of a fingertip like virtual globes (no need for various map projections here!). Other images can be zoomed in and out and scrolled across the screen. Additional data on various solar system objects is also tucked away in the app, some of which is provided by the WolframAlpha search engine if the iPad is connected to the Internet. The app also boasts an exclusive instrumental “launch track” written and performed by Björk, with an accompanying animation and slide show, although it’s really a standalone feature not otherwise integrated into the app.

The publishers call Solar System for iPad a “breakthough electronic book”, but that seems misleading in two respects. It is not an e-book in the same manner as those sold for Amazon’s Kindle or Apple’s own iBooks, which are as text-centric as conventional books. It is more of a standalone multimedia application, sold through Apple’s iTunes App Store and not though its separate iBooks bookstore. In fact, it is a close cousin of the multimedia astronomy CD-ROMs that became popular in the mid and late 1990s, during that window of time after computers equipped with CD drives became common but before broadband Internet connections did. That makes it much less “breakthough” than one might think.

What both Sizing Up the Universe and Solar System for iPad demonstrate is the challenge of trying to communicate the scale and nature of the universe. New approaches, and new technologies, can help in some ways, but the “mind-bogglingly big”—and often equally bizarre—universe remains a challenge to comprehend.