The flight of the Big Bird (part 3)The origins, development, and operations of the KH-9 HEXAGON reconnaissance satelliteby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The pilots played a grownup, top secret version of the arcade game where you put some quarters in a machine and maneuver a claw to grasp a chintzy stuffed animal. |

The whole thing seems nuts in retrospect, but by 1971 it was a well-proven technique: at 20,000 feet (6,000 meters) the pilot would depressurize the cargo bay and the recovery crew would extend two poles out the back of the aircraft. Strung between the two poles was a cable with grappling hooks every few feet along its length. The big parachute was 40 feet (12 meters) in diameter and too wide to fit between the two poles, so it had a cone-shaped extension at the top 15 feet (4.6 meters) and 12 feet (3.7 meters) in diameter. Load-bearing lines ran all the way from the capsule to the top of that cone. At 15,000 feet (4,500 meters) the C-130 pilot lined up on the parachute and then caught it at the top—that fabric cone—with the cable. The grappling hooks snagged the parachute, collapsing it, and the cable with its precious cargo was hauled into the plane’s cargo bay. The Air Force had been doing this regularly for over a decade and it worked well.

Except this time it didn’t. What most likely happened was that the parachute tore and collapsed and the cable did not grab it and the little capsule fell, streaming its parachute, 15,000 feet to the ocean below.

Satellite recoveries were big, complex, expensive efforts. In addition to seven planes in the air, the Air Force also operated two ships—yes, Air Force ships—the Sunnyvale and Longview, and several H-3 helicopters. They were present to recover a capsule that landed in the ocean. The capsules—known as “buckets” because they looked like large kettles—were designed to float, for a while. Earlier buckets were equipped with a plug consisting of compacted salt, and later, brown sugar, which was designed to dissolve within 24 hours, flood the capsule, and allow it to sink. But something went wrong here as well. Perhaps the capsule hit the water so hard that it ruptured the bucket’s exterior. Maybe it never came to the surface again. Or maybe the surface recovery forces did not arrive in time. But the capsule sank… in over three miles of water.

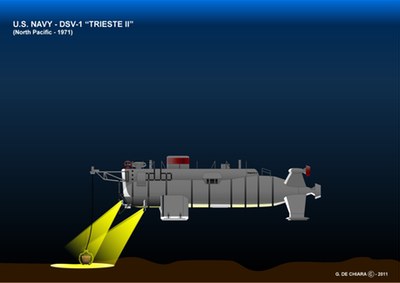

In spring 1972, nearly as far below the Pacific Ocean as the Herky Birds had been above it, three Navy pilots guided a different vessel, closing in on their film capsule. The Deep Submergence Vehicle Trieste II was at 16,400 feet (5,000 meters). It was dark and cold at this depth, and the only light came from the floodlights on the Trieste mounted on her bow and on either side of her crew capsule. The pilots played a grownup, top secret version of the arcade game where you put some quarters in a machine and maneuver a claw to grasp a chintzy stuffed animal.

At the front of the Trieste, hanging from a cable attached to a bow strut, was a large, four-pronged claw. The pilots deftly maneuvered the deep sea submersible near the bucket, lowered slightly, and then closed the claw. With the bucket securely grasped, they began the long, slow trip back to the surface and their support vessels.

The bucket contained thousands of feet of exposed film of millions of square miles inside the Soviet Union. The film showed submarine bases and missile silos and chemical weapons storage facilities. The film was taken by the first KH-9 HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite, a complicated behemoth that represented the epitome of American technological know-how.

The U.S. Navy's Deep Submergence Vehicle Trieste II. Three pilots operated the craft from the pressure sphere near the center. The legs indicate that the craft could settle on the ocean floor and equipment could be mounted at the bow. (credit: US Navy) |

The Big Bird flies

The story of the KH-9 HEXAGON’s operational life begins with water and ends with fire.

In mid-1971 the first KH-9 HEXAGON spacecraft—all 25,000 pounds (11,400 kilograms) of her—sat atop her Titan IIID launch vehicle at Space Launch Complex 4 East at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. She had been shipped by truck all the way from Lockheed’s Sunnyvale facility 250 miles (400 kilometers) away. Lockheed’s engineers had brought all the pieces together: the four reentry vehicles; the camera system built by Perkin-Elmer of Danbury, Connecticut; and the Lockheed-manufactured Satellite Control Section that provided power and stabilization and was equipped with a rocket engine for reboosting the spacecraft’s orbit after the atmosphere dragged it down. The components were fitted into the “spacecraft basic assembly” and everything was connected and tested and re-tested and finally approved for launch before it was sent to Vandenberg.

| The KH-9 was instantly successful and a worthy replacement for the CORONA search satellite. |

On June 15 the rocket roared to life and boosted the satellite high over the Pacific Ocean, heading south. The Titan’s big solid rocket boosters burned out and fell away, impacting into the blue water below. The Titan’s core rocket stage continued firing, and soon the payload fairing that protected the big satellite cleaved off and fell away, exposing the HEXAGON to the coldness of the extreme upper atmosphere. The Titan’s first stage fell away and the second stage fired. Not much later, the satellite separated from the second stage.

The HEXAGON was equipped with its own propellant and a small rocket engine. This engine fired to make final corrections to the orbit, placing the big heavy satellite at the right altitude. At the rear of the spacecraft two poles rotated outward and then long thin solar panels began to spread out, like an accordion. As soon as they were exposed to the sun the panels began producing electricity that flowed into the satellite’s batteries.

This first HEXAGON mission was designated mission 1201. Although not much is known about it, the flight apparently did have some hiccups. According to a recently declassified document, the spacecraft was placed in a “higher than optimum altitude,” although it is unclear why that happened. The orbit did not have an overly adverse effect upon the mission, however.

Soon the satellite’s command system turned on the camera system, and film began running at high speed through its camera, filling up the first of its reentry vehicles. When it was full, a guillotine sliced the film, a small door snapped shut sealing the exposed film inside the vehicle, and it detached from the bus-sized spacecraft. The reentry vehicle started spinning for stabilization and then a small rocket fired just enough to kill some of its orbital momentum. It started to fall toward the Earth, encountered the edges of the atmosphere, and began glowing. The vehicle was covered with a material that heated up, charred, and flaked away, carrying heat with it and protecting the vital film inside.

This first spacecraft had four reentry vehicles. Of those four, three were successfully recovered by the 6594 Test Group’s C-130s. The third one to come down ended up in the ocean. (See “Deep ops”, The Space Review, November 1, 2010)

Despite this hitch, the KH-9 was instantly successful and a worthy replacement for the CORONA search satellite. On June 28, not even two weeks after the launch, acting Director of Central Intelligence Robert Cushman briefed President Richard Nixon on developments in Soviet strategic weapons relevant to the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty that Nixon’s administration was currently negotiating with the Soviet Union. After discussing Soviet anti-ballistic missile systems and new ICBM silo construction, Cushman finished by telling Nixon about the HEXAGON, which Cushman said “will substantially improve our intelligence collection capabilities.”

According to Cushman, by June 28 they had already received two capsules of film. He then showed Nixon photographs of the Severodvinsk shipyard, which produced the Yankee class ballistic missile submarines that were roughly equivalent to the U.S. Navy’s Polaris missile subs. He compared the photos to those produced with the earlier CORONA satellite. Cushman finished by saying that by the time SALT talks began in Helsinki on July 8 there was a good chance that the United States “will have a more definitive count of the new ICBM silos under construction.”

| Within just a few short weeks a single HEXAGON spacecraft could photograph nearly the entire Soviet Union taking pictures so good that analysts working in darkened rooms back in Washington’s Navy Yard could make a precise count of every single Soviet ICBM silo in operation or under construction, and identify the type. |

As numerous American intelligence officials have stated over the years, satellite reconnaissance revolutionized intelligence collection. Albert “Bud” Wheelon, who headed the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology from 1962 to 1964 and initiated development of HEXAGON, wrote that “it was as if an enormous floodlight had been turned on in a darkened warehouse.” Unlike spies, satellites didn’t lie, they didn’t turn traitor, they didn’t forget or invent data, or get captured and imprisoned. But far more importantly, they produced massive volumes of data. HEXAGON may seem anachronistic today: thousands of people were involved in designing it and building it, and it was launched into orbit atop a large rocket, and a dozen planes and helicopters trekked out into the Pacific Ocean to bring back a tiny little capsule filled with tightly-wound film. But that film contained so much information that it was staggering.

Each sweep of one of HEXAGON’s cameras encompassed thousands of square miles of territory in the Soviet Union at a resolution that was better than three feet (one meter) on the ground. This made it particularly valuable for the arms control negotiations that the United States was then entering into, because within just a few short weeks a single HEXAGON spacecraft could photograph nearly the entire Soviet Union taking pictures so good that analysts working in darkened rooms back in Washington’s Navy Yard could make a precise count of every single Soviet ICBM silo in operation or under construction, and identify the type. They could count nearly every bomber sitting on an airfield and every submarine moored alongside a pier. The only impediment was weather—i.e. clouds. But if the skies were clear, HEXAGON was on the hunt and there was nowhere to hide.

Going operational

Mission 1201 was followed in January 1972 by Mission 1202, Mission 1203 in July, and Mission 1204 in October, all roaring aloft from Vandenberg’s Space Launch Complex 4 East. Whereas the CORONA spacecraft launched at approximately one-month intervals, the initial pace for the HEXAGON was much slower, although it carried twice as many reentry vehicles.

On March 9, 1973, the fifth KH-9 was launched into orbit. This one carried something new, a mapping camera and its own reentry vehicle—HEXAGON’s fifth—both mounted at the front of the large spacecraft. The inclusion of this mapping camera was somewhat controversial within the intelligence community, and the CIA had at one time opposed it. The camera was most likely developed by Itek, the same company that had built the CORONA reconnaissance camera—and also had a major rift with the CIA in 1965 over the development of the FULCRUM camera system that had eventually led to Perkin-Elmer building the HEXAGON. Perhaps the CIA’s opposition to the mapping camera simply had to do with issues of mass and volume. Or perhaps the lingering bad feelings toward Itek over the FULCRUM incident had contributed to this.

Although the NRO has not declassified Itek’s involvement with the mapping camera, there are a number of clues about its manufacturer and pedigree. In 2002 the US government declassified most of the mapping imagery taken by the twelve HEXAGON missions that carried a mapping camera. This consisted of approximately 29,000 images, each covering nearly 1,300 square miles (3,400 square kilometers). At the time the government released almost no other information about the cameras that actually took the images. Each mapping mission took approximately 2,400 frames. The images had 1,058 little crosses on the images known as reseau marks and enabling mapmakers to take precise measurements. These details help to connect the KH-9 mapping camera’s unknown manufacturer to its origins and its descendent.

In 1966, Itek produced a feasibility study for a Geodetic Orbital Photographic Satellite System, or GOPSS. GOPSS was a proposal for a mapping spacecraft similar to CORONA and using essentially the same rocket and spacecraft. The Itek mapping camera would have had a 9.05 x 18.1 inch (23 x 46 centimeter) frame format and a 12-inch (30.5-centimeter) focal length. GOPSS was never built, but the focal length and frame format are the same as the mapping camera carried aboard the KH-9 missions.

| The decision to include a mapping camera on HEXAGON may have been made easier by several other bureaucratic and programmatic developments. |

In the early 1980s NASA announced that an upcoming space shuttle mission would carry a Large Format Camera developed by Itek. The LFC was intended for topographic mapping. It only had 45 reseau marks compared to the 1,058 for the KH-9 camera. At the time, NASA apparently had plans to regularly carry the LFC aboard shuttle missions. Five flights would have been required to cover all of the terrain below shuttles launched from Florida. Presumably shuttles flying to polar orbit would have also carried the LFC as well, covering northern latitudes. Although there is no information to support it, it seems reasonable to conclude that the LFC was going to replace the KH-9 mapping camera. But the LFC flew on only a single mission, STS-41G with space shuttle Challenger in October 1984. When the Air Force canceled shuttle missions flying to polar orbit after the January 1986 Challenger accident, large parts of the Earth’s surface could no longer be mapped that way. The intelligence community must have developed an alternative using the KH-11.

According to a declassified schematic of the basic KH-9 layout, the mapping camera was mounted at the front of the spacecraft, stretching it out to 53 feet (16 meters) in length. When the mapping camera imagery was declassified in 2002 the missions included the suffix “5” indicating that the film had been returned in a fifth reentry vehicle. Because the film was approximately nine inches in width, it could easily fit in the kind of reentry vehicle originally manufactured by General Electric for the CORONA and later adapted for the GAMBIT and designated as the Mk V. A history of the 6594th Recovery Group indicates that they regularly recovered Mk VIII reentry vehicles—the big ones developed for the KH-9—and Mk V reentry vehicles like those used by the KH-8. The fact that the history does not mention a third type of recovery vehicle indicates that the mapping imagery was returned either in a Mk VIII or a Mk V, and the Mk VIII was probably larger than required.

The decision to include a mapping camera on HEXAGON may have been made easier by several other bureaucratic and programmatic developments. In the summer of 1971, just as HEXAGON was taking flight, the CIA had pitched another large reconnaissance satellite to President Nixon. This one was even more revolutionary than the HEXAGON. It was a “near-real-time” system that did not even use film but took images electronically and beamed them to the ground. On September 23, 1971, Nixon approved a plan to develop the KH-11 KENNAN. Because HEXAGON was already developed and the CIA would have its hands full with the KENNAN, the agency agreed to transfer responsibility for the HEXAGON’s camera from the CIA’s Sensor Subsystem Program Office to the National Reconnaissance Office’s Program A, the West Coast Directorate of Special Projects. The CIA agreed to provide full engineering support to Program A during the transition. Perhaps the transfer made it easier for the NRO to include the mapping camera on the HEXAGON because the CIA was no longer involved. This also might have become even easier when the last KH-4B CORONA satellite flew in May 1972 and there was no other source of mapping imagery.