When will our Martian future get here?by Andre Bormanis

|

| For those of us who dreamed of trips to Mars, the trouble with our times, as Paul Valery once said, is that the future is not what it used to be. |

For those of us who grew up in the Space Age, the 21st century was supposed to look a whole lot different. I remember seeing a beautiful model of the “city of the future” on a visit to Disneyland in 1970. It depicted what urban life might be like in 1988, a year that had a very far-future vibe at the time. Elegant monorails connected towering skyscrapers and geodesic domes in a lush setting of green parks and pristine waterways. The Concorde SST began service a few years later, and was widely assumed to be the prototype for a new era of supersonic travel. By the time the even more science fictional 21st century rolled around, certainly NASA would have a fleet of nuclear rockets routinely ferrying astronauts to and from Mars. What a beautiful world it would be. And at the time, it was a fairly credible vision of the future.

Of course there have been significant improvements in trains, planes, and automobiles over the past fifty years, and extraordinary advances in many fields, particularly consumer electronics, the Internet, and biotechnology. These changes have had a profound impact on the way we live, but in terms of the physical dimensions that define our day-to-day world, they occupy the nooks and crannies of modern life. At larger scales—the buildings and transportation systems that dominate the infrastructure of civilization—the world still looks pretty much as it did ten, twenty, even fifty years ago. For those of us who dreamed of trips to Mars, the trouble with our times, as Paul Valery once said, is that the future is not what it used to be.

But is the future we find ourselves in really such a bad place? Different than we hoped for, certainly. But in some ways, perhaps, even better than we imagined. The Internet, for example, has opened space exploration to everyone. Amateur space enthusiasts routinely process images taken by robotic spacecraft and telescopes that professional scientists don’t have time to study in detail, sometimes leading to important discoveries. Recently, a ten-year-old girl in Canada found a supernova by poring over images of distant galaxies taken by an observatory on New Year’s Eve and downloaded to her desktop computer.

As bandwidth increases, virtual exploration will become ever more compelling, richer in detail, and deeper in content. A new paradigm is emerging: interplanetary exploration from the comfort of your own home. Call it “virtual exploration.” But is this mode of exploration a legitimate substitute for living, breathing astronauts?

Steve Squires, Principal Investigator for the Mars Exploration Rover Program, has said that a human geologist, in a single day, could accomplish as much as his rovers achieve in three months’ time. Assuming this is true today, it begs the question of whether it will be true tomorrow. It seems unlikely that NASA, or any other space agency, will undertake a human mission to Mars before the late 2030s. Given the rate at which robotic technology is advancing, one can safely posit that robots will be exponentially more capable thirty years from now than they are today. A computer has just beaten a pair of Jeopardy! champions at a game that requires a particularly human form of cleverness. How long will it be before they can outdo an experienced rock hound?

It seems likely that autonomous robot geologists will soon come close to being able to do anything that their human counterparts can do, without the need for life support systems, medical care, intensive psychological preparation, or a way home. In addition to order of magnitude cost savings, there would be much less concern over contaminating the currently pristine Martian environment.

| Future generations may view our current plans for sending astronauts to Mars as we view an earlier generation’s dreams of personal jet packs and flying cars: technically achievable, but utterly impractical for economic and political reasons. |

Another commonly cited reason for establishing a human presence on Mars is to provide an “insurance policy” for our species. If disaster were to befall the home planet—a large asteroid strike, super-volcano eruption, or some other civilization-wrecking catastrophe—a small, off-world colony of humans would guarantee the survival of the species. Well, maybe. At least hundreds of people would need to populate such a colony to enable a genetically viable breeding population. A Mars colony on that scale is hard to conceive of anytime soon. And certainly it would be far easier to create such a sinecure here on Earth—underground, or in some other sealed, protected environment—than it would be on another world.

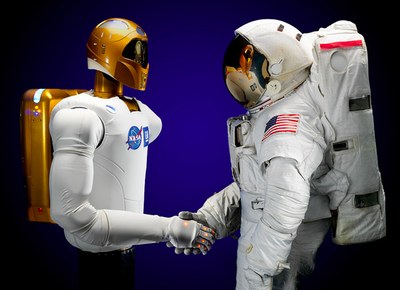

In the coming decades, armies of robots could be scouring the Red Planet for past or present signs of life. Designed specifically for that purpose, they could conduct that search far more cheaply and efficiently than us fragile humans could ever hope to. These robots may even be humanoid in appearance and function, like the “Robonaut 2” model Discovery is currently delivering to ISS. While not as sophisticated as Star Trek’s Commander Data, the sixth or seventh generation model may prove to be a very capable geologist and chemist. The popularity of fictional robots in film, and the emotional attachment many people have developed to the Opportunity and Spirit rovers, attests to the intense public interest (and concomitant federal funding) that silicon explorers can inspire.

The robots of tomorrow may take a form we can’t imagine, but through their cameras and sensors, we’ll explore along with them. Building data sets with sufficient detail to image large swaths of Martian terrain at centimeter scales is already happening. One can easily imagine a home entertainment system that incorporates both a 3-D, immersive visor and an omni-directional treadmill. Inside this primitive Holodeck, scientists and interested laypeople could wander the Martian landscape at their leisure, seeing what lies over the next hill or in a nearby canyon, without ever leaving the comfort and safety of Earth.

| Clearly, virtual exploration can whet the appetite for the real thing. |

It’s possible that some unforeseeable breakthrough in astronautics will make human spaceflight beyond LEO much easier and less expensive, perhaps within reach of a private consortium of wealthy individuals and corporations. But it seems more likely that in the current century, robots will be the pioneers of the Martian frontier, not humans. Future generations may view our current plans for sending astronauts to Mars as we view an earlier generation’s dreams of personal jet packs and flying cars: technically achievable, but utterly impractical for economic and political reasons.

On the other hand, an emphasis on virtual exploration could be an unexpected gift to advocates of the human variety. Google has recently launched a virtual art museum project. Through the Internet, users can tour seventeen major museums in the US and Europe, examining their collections at leisure, zooming into a particular piece of art to explore it in greater detail than in-situ patrons are ever allowed to do. Contrary to expectations, the availability of virtual tours has increased attendance at these museums. Clearly, virtual exploration can whet the appetite for the real thing.

I suppose it would be ironic if a greater focus on the virtual exploration of Mars in the near-term precipitates increased public support for human exploration in the long-term. But life is full of ironies, and in this case, a little irony would be welcome.