The Big Bird and the turkeyby Dwayne A. Day

|

| What is known is that people within the NRO resisted launching its satellites on the shuttle—some Air Force officers derisively referred to it as “the turkey”. |

From a space policy perspective, the shuttle represents the biggest decision of the last four decades. When President Richard Nixon approved the shuttle in 1972, this set in motion a series of policies requiring the transfer of all American spacecraft to the shuttle (also designated the “Space Transportation System,” or STS) and the eventual shutdown of expendable launch vehicle production—i.e. the cancellation of the Atlas, Titan, and Delta launch vehicles that carried American intelligence satellites.

There were a lot of dissenting voices within the military and intelligence communities in the years after this decision. Unfortunately, relatively little is known about this dissent because often it was linked with the highly-classified payloads that the NRO would have to launch on the shuttle. What is known is that people within the NRO resisted—some Air Force officers derisively referred to the shuttle as “the turkey” (see “The spooks and the turkey”, The Space Review, November 20, 2006, and “Big Black and the new bird: the NRO and the early Space Shuttle”, The Space Review, January 11, 2010).

It is not difficult to imagine why they resisted. Setting aside any reservations that they had about the reliability and cost of an unproven vehicle like the shuttle, there would naturally have been substantial costs associated with redesigning spacecraft to fly on a shuttle. Spacecraft are designed for certain vibration, noise, acceleration, and other environmental conditions. Change those conditions and the spacecraft have to be modified. A major issue for adapting payloads for shuttle launch was that the shuttle holds them differently inside its payload bay compared to an expendable rocket. Instead of sitting in a stack, with all the weight resting on the bottom, payloads in the shuttle had to be suspended along their length. Try to imagine redesigning a layer cake so that you do not pick it up from the bottom but hold onto it from the sides and you get a sense of the engineering challenges.

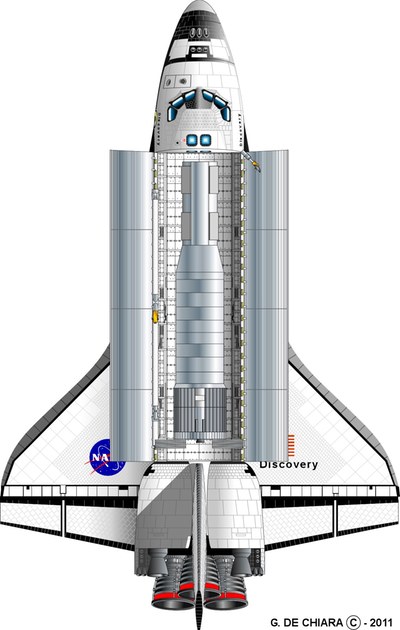

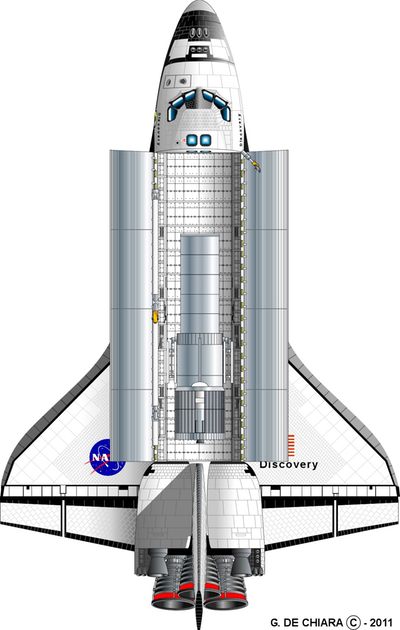

There were a number of NRO spacecraft that were being launched regularly during the 1970s as the shuttle was under development. The massive KH-9 HEXAGON—nicknamed “the big bird”—entered service in 1971 and was being launched a couple of times per year. As demonstrated by Giuseppe De Chiara’s illustration, the KH-9 could have fit within the shuttle’s payload bay with a little room to spare.

An illustration showing how a KH-11 satellite would have fit into the shuttle’s cargo bay. (larger version) (credit: © Giuseppe de Chiara) |

But was the KH-9 ever evaluated for possible shuttle launch? It is likely that the NRO conducted some kind of preliminary review to determine which spacecraft could and should be launched on the shuttle. One possible reason to not convert the HEXAGON for shuttle launch was that it was a legacy system that would eventually be replaced; changing the design when the eventual termination date was in sight may not have been economically sound. But that raises the question of when such an evaluation was made, and when the KH-9’s decommissioning was planned. NASA’s original goal for shuttle was to put it into operation by 1978, but full operational status did not happen until 1982, and the flight rate was much lower than predicted. The HEXAGON’s last flight—which ended in a spectacular launch explosion—took place in April 1986 (see “The flight of the Big Bird (part 4)”, The Space Review, March 28, 2011). We know that the shuttle’s availability slipped, and it is possible that the KH-9’s service was also stretched out by several years.

| One possible reason to not convert the HEXAGON for shuttle launch was that it was a legacy system that would eventually be replaced; changing the design when the eventual termination date was in sight may not have been economically sound. |

Although we do not know if the HEXAGON was considered for shuttle launch, we do know that NRO managers resisted converting spacecraft to the shuttle until forced to do so by NRO Director Hans Mark in the late 1970s. We also know that shuttle offered size advantages over the Titan III. In particular, the shuttle could carry wider payloads. Giuseppe De Chiara has illustrated the KH-11 KENNAN, which entered service in late 1976 and eventually supplanted the KH-9, inside a shuttle payload bay. Unclassified documents indicate that the NRO sought to exploit the shuttle’s wider payload bay by expanding the propulsion module at the rear of the KH-11. The Hubble Space Telescope, which began construction in the 1980s, used a wider diameter equipment ring that was probably developed for this upgraded version of the KH-11, sometimes referred to as the “KH-12” by independent observers. Thus, the follow-on to the initial KH-11 series depicted in this second illustration was probably thicker at the base. However, the Challenger accident led to a cancellation of the policy of moving all national security payloads to the shuttle. If this upgraded KH-11 did eventually enter service, it probably never flew aboard the Space Shuttle, but instead used the Titan IV.