Fifty years of NASA artby Jeff Foust

|

| “Different artists have been attracted to the program in different ways,” said Crouch. “All of them give you the artist’s-eye view of what was going on.” |

Nearly half a century ago, NASA established a program that gave artists access to the agency’s facilities and projects, providing a way to reach the public in ways that go beyond photos and press releases. A collection of works created under the NASA Art Program, called “NASA | ART: 50 Years of Exploration”, has been touring the country since late 2008, finally arriving Memorial Day weekend at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington.

The exhibit, located in the same gallery at the museum that hosted a collection of former astronaut Alan Bean’s paintings two years ago (see “When space and art intersect”, The Space Review, September 9, 2009), features a selection of artworks—primarily, but not exclusively, paintings—made by participating artists in the NASA Art Program since the early 1960s. There is a heavy emphasis on human spaceflight, with sections devoted to the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, and Space Shuttle programs, but there are also paintings associated with NASA’s robotic space missions and its underappreciated aeronautics work.

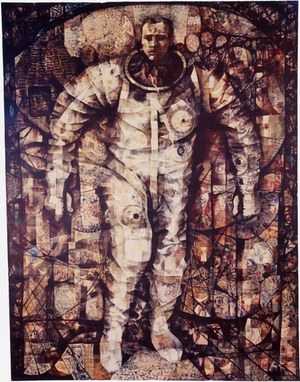

There is a wide variety of artistic styles represented in the exhibit. Some artists opt for realism: one painting showing Endeavour after landing on its maiden flight looks at first glance like a giant photograph. (That painting has an added degree of poignancy as Endeavour prepares to land this week on its final mission.) Others are more abstract, some to the point that, without the accompanying description, it would be all but impossible to link it to NASA and spaceflight.

“Different artists have been attracted to the program in different ways,” said Tom Crouch, the senior curator for art at the museum, during a preview of the exhibit last week. “You’ll see paintings that are symbolic, heavily symbolic, and paintings that are representational. All of them give you the artist’s-eye view of what was going on.”

While many of the artists on display aren’t household names, a few are instantly recognizable. Norman Rockwell painted Gus Grissom and John Young getting suited up for the first Gemini flight in his distinctive style; NASA loaned Rockwell a Gemini spacesuit to help him make the paining as realistic as possible. Realism was less of a concern of Andy Warhol, whose pop art take on the photo of Buzz Aldrin standing on the lunar surface with the American flag is included in the exhibition. (“It’s definitely a different take on the Apollo era,” said Bert Ulrich, the current curator for the NASA art program, who added that this work was not commissioned by the program but instead donated to it. “You have Buzz Aldrin standing there in neon pink.”) And famed portrait photographer Annie Leibovitz has a photo of Eileen Collins, the first woman to command a shuttle mission, in the exhibition.

Barbara Ernst Prey describes the work that goes into her NASA painting, such as one of the X-43 hypersonic aircraft (right) on display in the exhibit. (credit: J. Foust) |

Other artists have been attracted to the program by their fascination with the subject matter and the challenge of depicting something that is often quite literally out of this world. “How do you paint the fastest aircraft in the world?” asked Barbara Ernst Prey, whose depiction of the X-43 experimental hypersonic plane is included in the exhibition. She chose the realistic approach, but one that conveyed “a strip of energy going across the blue sky.”

Prey said she does considerable research for her NASA paintings, which have also included shuttle launches and the International Space Station. For the X-43 painting she was able to get up close to the X-43 an hour before it took off, attached to its B-52 carrier plane, making sketches she later used for her painting. For her later ISS painting she spent six months doing research, seeing elements of the station prior to launch and also building a model. “There’s a lot of time I’ve spent on this work, but it’s been so rewarding. As an artist, you give and it comes back: you learn so much and you bring that back into your work.”

| “At first, the people at places like the Cape really didn’t know what to make of a group of artists showing up,” Dean said. “But when they saw their routine job being turned into art, things changed.” |

Such access to NASA facilities is not unusual for participating artists. Over the years artists have been able to see up close launches and the preparations for them, as well as the astronauts themselves. One artist, Paul Calle, was even present as the crew of Apollo 11 suited up for launch, sketching them. That attracted the attention of Michael Collins, who, curious about Calle’s work, asked to see the sketches just a few hours before blasting off on his historic mission.

But why does NASA even have an art program in the first place? The idea, said James Dean, who led the program in its early years, was the idea of then-administrator James Webb during the Mercury program. Webb was initially interested in a group portrait of the Mercury astronauts, but expanded that to include a broader documentation of NASA’s activities by artists. That Mercury group portrait was never made, but it did result in the formation of the agency’s art program. “We saw it as really reaching an element of the public that perhaps wouldn’t be too interested in science,” Dean said.

There was, of course, plenty of still and motion photography of the space program, but that imagery, Dean said, failed to fully document what NASA was doing. “There was something missing, and we determined that it was the excitement you felt when you actually saw all of this take place,” he said. “Here’s something that artists could really help us with: communicate the excitement of what was going on.”

An initial group of artists went to Cape Canaveral to document the launch of the final Mercury mission by Gordon Cooper in 1963; their works were exhibited at the National Gallery of Art two years later. A second exhibition at the National Gallery took place in late 1969, just a few months after the Apollo 11 mission. That second exhibition, Dean recalled, was planned immediately after the launch, giving artists only a few months to prepare their works.

The idea of artists traipsing around the Cape and other NASA facilities during the frenzied era of the Space Race was met by some at the agency with befuddlement at first, but later acceptance. “At first, the people at places like the Cape really didn’t know what to make of a group of artists showing up,” Dean said. “But when they saw their routine job being turned into art, things changed.”

Nichelle Nichols, who played Uhura on Star Trek, offers her thoughts on a painting in the exhibit showing both the space shuttle and starship Enterprise. (credit: J. Foust) |

One of the pieces of art in the collection—arguably one of the kitschier pieces of pop art—shows two Enterprises: NASA’s space shuttle Enteprise, in orbit, and in the distance, the starship Enterprise from Star Trek fame. As it turned out, one of the special guests at last week’s preview of the exhibit was Nichelle Nichols, best known as Uhura from the original Star Trek series and movies. She commented a bit about that piece, but also about the exhibit in general.

“The whole exhibit is the arrogance of man’s imagination,” she said. By arrogance, she added, she wasn’t implying the negative connotation normally associated with the term, but instead more the force of will required to turn dreams into reality. “This is what all the art is: to imagine what it is that takes us from ground zero to as far as the imagination can take you—and then beyond.”