VASIMR and a new war of the currentsby Chuck Black

|

| According to Zubrin, the current focus on new technologies (especially VASIMR) is postponing, not facilitating space exploration and “only useful as a smokescreen for those who wish to avoid embracing” real initiatives which could begin now. |

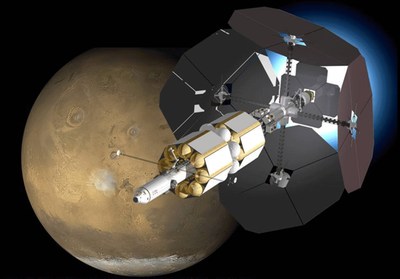

Zubrin, the author of The Case for Mars: The Plan to Settle the Red Planet and Why We Must (see “Reviews: Revisiting the Moon and Mars”, The Space Review, July 5, 2011) has singled out the Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket (VASIMR) electromagnetic propulsion system for spacecraft; the Ad Astra Rocket Company, which is presently involved in researching and commercializing VASIMR; plus former astronaut and current Ad Astra president and CEO Franklin Chang-Diaz, who is credited with being the inventor of the technology (see “VASIMR: hope or hype for Mars exploration?”, The Space Review, September 7, 2010). So what’s the problem?

Well, according to a commentary written by Zubrin for Space News last month titled “The VASIMR Hoax”, the current focus on new technologies (especially VASIMR) is postponing, not facilitating space exploration and “only useful as a smokescreen for those who wish to avoid embracing” real initiatives which could begin now, using existing technology as outlined by Zubrin in his recent Wall Street Journal essay “How We Can Fly to Mars in This Decade—And on the Cheap” (see also “A transorbital railroad to Mars”, The Space Review, May 23, 2011).

And this latest editorial doesn’t just have a title packed with hyperbole. Zubrin also explicitly calls VASIMR a “total falsehood” which “must be exposed.” Best of all, the only way for the truth to prevail is for the people to attend a panel discussion titled: “VASIMR: Silver Bullet or Hoax” at the next Mars Society international convention in Dallas later this week.

Of course, the real story is far more complex. First of all, electric space propulsion systems (of which VASIMR is just one of many and perhaps not even the best) need lots and lots of electricity. Zubrin is indeed correct in the article when he states that:

To achieve his much-repeated claim that VASIMR could enable a 39-day one-way transit to Mars, Chang-Diaz posits a nuclear reactor system with a power of 200,000 kilowatts and a power-to-mass ratio of 1,000 watts per kilogram. In fact, the largest space nuclear reactor ever built, the Soviet (era) Topaz, had a power of 10 kilowatts and a power-to-mass ratio of 10 watts per kilogram.

But while Zubrin is also correct in his assessment that the current administration is “not making an effort to develop a space nuclear reactor of any kind” he omits to mention past and current efforts by the US and others, some of which are outlined in a November 2009 Wired.com article titled, “Russia Leads Nuclear Space Race After U.S. Drops Out.”

Of course, we can’t forget that there are also substantial difficulties testing and assessing electrical propulsion systems. For example, the theories covering the behavior of the magnetic nozzles used by the systems are a complex mash-up of theory and guesswork, which often provides unreliable predictions at variance from any measured, real world performance.

| In essence, both Zubrin and Chang-Diaz are exaggerating their present case. Why would they be doing this? |

The testing mechanism requirements are also quite complex. For instance, testing the magnetic nozzle requires a test volume that’s large enough for the plasma to fully separate from the magnetic field so as to insure that the outer fringes of the field aren’t dragging on the plasma and killing most of the thrust that the inner parts of the field are producing. This means you need a huge vacuum chamber to perform any sort of accurate test of an electrical propulsion engine and the chamber needs to be capable of a very high vacuum during the test since even small amounts of residual gas can mess up electric-thruster measurements.

Of course, you could test the engine in space, which is big and has vacuum pretty much everywhere. But the only place presently available for this sort of testing is aboard the International Space Station (ISS), which has been considered and hinted at by the US and NASA, but is not yet formally scheduled for the VASIMR.

However, we do know that electrical propulsion systems in general work. The ion thruster developed for the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) “Hayabusa” mission, which is a small scale, low powered electrical propulsion engine similar to VASIMR has demonstrated its feasibility during interplanetary flight under real world conditions for over a thousand hours of continuous use during its seven year mission to retrieve a sample from the small near-Earth asteroid 25143 Itokawa.

And Hayabusa isn’t unique. The NASA launched Dawn spacecraft which has just entered orbit around the asteroid Vesta, uses xenon ion thrusters pioneered during the Deep Space 1 probes, a part of the NASA New Millennium Program focused on testing high risk technologies. There are others as well, which means that VASIMR is certainly not a hoax, but it also suggests that perhaps Chang-Diaz is a bit more optimistic in his claims for this specific propulsion system than the existing evidence warrants.

In essence, both Zubrin and Chang-Diaz are exaggerating their present case. Why would they be doing this? That’s easy. Both realize that science and engineering are starting to take a backseat in space exploration to public relations and entertainment.

But this is nothing new. We’ve been here before with new technology and scientific advancement, most memorably during the great “war of the currents” beginning in the 1880s between American entrepreneurs George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison, who became adversaries because of Edison’s promotion of direct current (DC) for electric power distribution over the alternating current (AC) advocated by Westinghouse and the eccentric but gifted inventor Nikola Tesla.

In this battle, Edison was the incumbent with an existing infrastructure of DC power generators and transmission facilities providing power to major US cities like New York and Philadelphia. But Westinghouse and Telsa had the newer, safer, and less costly AC technology with its ability to travel longer distances from the source generator and suitability for a wider range of uses once matched with the appropriate transformer.

Of course, the advantages of AC current didn’t concern Edison, who had business concerns at risk. He described DC as “a river flowing peacefully to the sea, while alternating current was like a torrent rushing violently over a precipice,” according to biographers.

With the secret help of Harold P. Brown (the inventor of the electric chair) and ruthlessness comparable to any current aerospace lobbyist, Edison went about happily spreading rumors, buttonholing state legislators, and encouraging the public electrocution of dogs, horses, and eventually even a circus elephant, in order to demonstrate the “dangers” of the AC competition.

| Are we entering a new era where showmanship, entertainment, political glad-handling, pork-barreling and hyperbole will each be necessary in order to suitably move forward new technologies? |

The climax of the war came during the run-up to the Chicago Worlds Fair of 1893 with both Edison and Westinghouse competing for the electrical contract. Westinghouse eventually won (primarily due to his lower cost bid) and three years later, electrical power was being transmitted to industries in Buffalo from Niagara Falls using generators built by Westinghouse Electric Corporation using Tesla’s AC system patent. The war of the currents was over, although pockets of DC electricity remained in cities well into the 20th century.

It’s interesting to note that The Music Man by Meredith Willson, based on a story by Willson and Franklin Lacey, is set squarely in the American progressive era from 1890 to 1920, which was in many ways a reaction to the excesses of the preceding gilded age era of rapid economic and population growth in the United States from 1865 to 1890, when the great war of the currents occurred. This is reflected in the play by the ambiguity of the main character, the so called “professor” Harold Hill, who begins as a shiftless con artist but eventually follows through with his original promises, wins the girl and ends up the hero.

Are we entering a new era where showmanship, entertainment, political glad-handling, pork-barreling and hyperbole will each be necessary in order to suitably move forward new technologies? Only time will tell. But the idea of Bob Zubrin calling out Franklin Chang-Diaz for the modern day equivalent of a public gunfight at high noon for perpetrating a “hoax” doesn’t seem to strike anyone as being silly. So maybe the next “gilded age” has already arrived.