High expectations: Utopianism and cornucopianism in the early modern era and the Space Ageby John Hickman

|

| Uncharted continents populated by noble savages were taken as license to imagine or attempt to establish societies liberated from contemporary political, economic, and social constraints or to imagine wealth so immense that it banished economic scarcity. |

The word “utopia” is itself a product of the period. Sir Thomas More coined it to name the fictional country in his 1516 novel. The same longing for life in a county happier because it was better governed can also be read in both versions of Denis Veiras’s 1675–1679 utopian novel The History of the Sevarambians. Writing socially instructive fiction was not enough for many intellectuals. The New World presented opportunities to attempt the sort of radical social engineering that would never be tolerated by the conservative monarchical regimes ruling the Old World. The two most successful of these experiments were those of the English Puritans, who established a decidedly dour Calvinist theocracy in Massachusetts from 1630 to 1684, and the Jesuits, who organized the Guarani into Christian communes called the Paraguayan Reductions between 1610 and 1767. A less successful and less well known Jesuit project was undertaken by a Saxon Jesuit known to history variously as Priber, Pryber, or Preber, who ended his days in an English jail in South Carolina in the 1740s after attempting to establish a similar Christian commune among the Cherokee and Chickasaw. Ultimately and unsurprisingly the European monarchies reasserted control over their colonies in Massachusetts and Paraguay.

Even those transfixed by the possibility of material rather than spiritual gain could be carried away by the seeming limitlessness of the New World. The promise of El Dorado lured waves of adventurers, and even when they couldn’t find riches they could promise to find riches. Walter Raleigh’s 1596 The Discoverie of the Large, Rich and Beautiful Empire of Guiana described a country with stupendous gold mining potential. Gold was eventually found but in no way near the promised quantities. Today Guiana is a minor gold producer, as are a majority of countries on Earth.

What does all this pre-industrial wishful thinking about the Americas have to do with Space Age thinking about outer space? The most obvious parallel is that utopian and cornucopian expectation suffuses Golden Age science fiction. Consider, for example, how wise extraterrestrials bring peace rather than war in the 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still and Arthur C. Clarke’s 1957 novel Childhood’s End. Clarke’s extraterrestrials also put an end to racial discrimination, illiteracy, and poverty. What’s more, they do so non-violently with demonstrations of technological superiority and the issuance of clear instructions.

The less obvious parallel is to the utopian and cornucopian thinking that shaped the expectations of decision-makers responsible for the making international space law. Once again the encounter with an uncharted realm with immense potential inspired attempts to achieve what was understood to be impossible here on Earth. Invoking the spirit of internationalism, diplomatic representatives of the non-spacefaring states, and in particular those from Third World countries with scant hope of becoming spacefaring states, called upon the two spacefaring superpowers to cooperate in space and share without compensation the fruits of their celestial labors. Stationing nuclear weapons would be forbidden in orbit though not in divided Germany. National territorial sovereignty on celestial bodies would be forsworn by countries unwilling to resolve even minor terrestrial territorial disputes with their neighbors. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the core document of the international legal regime for space, is a monument to the internationalist utopian and cornucopian expectations of the 1950s and 1960s.

| Attempting to solve problems experienced here by attempting to realize the impossible over there or up there is a mistake. Geographic location, no matter how exotic, does not alter human nature. |

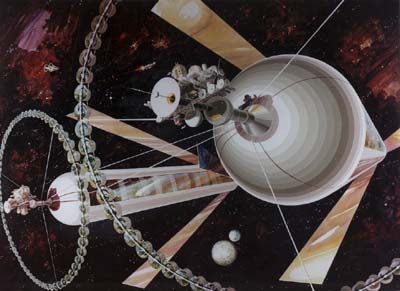

Utopianism and cornucopianism also characterized the expectations about outer space of those of a rather different ideological bent. Since the 1970s libertarians have conceived it as a realm where private firms might generate immense wealth if only it could be liberated from government. Unlike every other geographic frontier in modern history, outer space would be opened to development and settlement without the state. Gerard K. O’Neill’s massive orbital space colonies promised universal prosperity and the chance to build communities for every minority. Promises made in the 1980s were rather more restrained but even they failed to materialize. For example, McDonnell Douglas and Ortho Pharmaceuticals never produced billions of dollars worth of medicine in orbit.1 Orbital hotels have yet to materialize, unless one wants to count the government-built International Space Station.

What lesson should be drawn this comparison of the Early Modern Age and Space Age? Attempting to solve problems experienced here by attempting to realize the impossible over there or up there is a mistake. Geographic location, no matter how exotic, does not alter human nature. Successful institutions are likely to be replicated in new realms rather than transcended. Contrary to expectation, the more distant and more extreme the environment, the more we must rely upon already proven solutions to social, economic, and political problems.

1 Richard W. Stevenson. “Private Space Projects Lagging.” The New York Times. June 1, 1989.