Of ships and spaceby Stewart Money

|

| Whether by design or circumstance, certain ships sometimes assume a much greater role in human affairs than could ever be expected when their keels were first laid down. |

Britain was shocked. Although the ship’s vulnerabilities were well known to the British Admiralty, to the general public it was something else entirely: “The Mighty Hood,” a proud symbol of the vaunted British navy, and of England itself. In fact, the ship was committed to action against the superior Bismarck precisely because that ship was held in similar esteem by the German people, who, throttled by the British seapower in the first World War, were intent on establishing a surface naval threat of their own. The opportunity to thwart Germany’s naval ambitions by sinking their flagship was judged worth the risk. Humiliated at the loss of a national symbol; the Admiralty responded with one of the more famous commands in military history “Sink the Bismarck!”

This occasion early in the Second World War, though imbued with the extraordinary life or death drama that necessarily accompanies military conflict, highlights a particular aspect of human history and nature. Whether by design or circumstance, certain ships sometimes assume a much greater role in human affairs than could ever be expected when their keels were first laid down. We were reminded of this once again, as the United States witnessed the end of the Space Shuttle program. Of all the constructs built of human hands, perhaps nothing holds such a mystique as that of the ship. Whether they sail the ocean or space, ships can evoke a powerful response in the people and nations they serve.

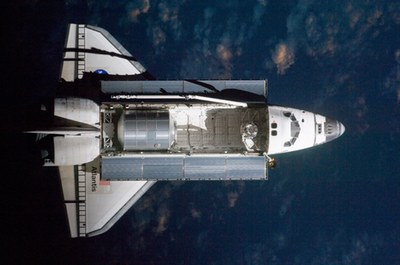

We know their names: Mayflower, Victory, Constitution, Titanic, Yorktown. The current year has seen the list grow appreciably. Reflecting upon the particular appeal evoked by Atlantis, sitting on the pad, in the rainy evening, prior to its final flight, it may be worth considering that pull exerted is simply a modern chapter in an age-old love affair. The shuttle was from an emotive standpoint at least, more than a spacecraft; it was our first, and so far only, true spaceship. Its absence may have more bearing on how the public considers spaceflight than one might expect.

Though neither the United States nor Great Britain are significant commercial shipbuilders any longer, our culture, at least part of it, still reflects much of its maritime heritage. From the masthead at the top of a magazine or paper, to reporting on which presidential candidate is best suited to be in the wheelhouse, to the son of a gun who was three sheets to the wind and let the cat out of the bag, because no one had showed him the ropes, ours is a language which derives much from our nautical history. And there is hardly a richer source of expressions to capture the range of fates that may befall us than that which derives from ships and the lore of the sea. More than a matter of quaint colloquialisms, whether the expression is drowning in debt, running into stiff headwinds, fighting a rising tide, having the wind at our back or waiting for our ship to come in, we often as not resort to the terminology of ships and the sea to express how we view the conditions of our lives, our institutions, and the nations in which we live.

| In comparison with what came before it, and apparently what is to come after—capsules both—one could look at a shuttle and see it exudes those elements of “shipness” which are instantly apparent. |

The one truth of any ship and its crew is that it lives in an element that cannot be controlled, but at best only managed. In addition to all else that it is and represents, as an instrument of policy; or vessel on a mission of exploration, mercy, commerce, peace, research or war; the ship that is resting at harbor, docked to a station, or waiting on the pad, eventually will be taken out into an environment of potentially uncontrollable fury that tests the cleverness of its designers, the strength of its sinews, and the will of its crew. This fact inextricably entwines the fate of ship and crew, and it is perhaps this fact that makes it so readily possible to revert to the ship as metaphor for our lives, and gives the concept of the ship a unique place in our culture.

As self-contained representations of national power and policy, a ship’s fate is frequently linked not only with that of her crew, but also with the nation under whose flag she sails. The US entered the Spanish American War on the battlecry “Remember the Maine,” entered the First World War partially in delayed response to the sinking of the Lusitania, and the Second World War with the loss of the Arizona and others in the attack on Pearl Harbor, and it was by no accident that the final act of the most terrible conflict in human history was performed on the deck of the most visible symbol of the United States, the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

It was perhaps then only natural that an American president, who had fought in that same war aboard the smallest of vessels on the largest of oceans, and who was never far from the sea and a sailboat, would seek to explain to the nation the challenge and opportunities of spaceflight in nautical terms. In his two signature speeches regarding the space program; the address before a joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961, in which he committed America to the Moon, and then at Rice University on September 12, 1962, President Kennedy referred to space as “this new ocean,” upon which the US “must sail.” And sail it did.

When the Apollo program gained its crowning national achievement on July 20, 1969, the indelible image presented was not of a ship, but of a man, Neil Armstrong, taking a simple, single, human action, “one small step.” In the wake of Apollo, however, as the US commissioned the Space Shuttle program and its fleet of orbiters to initiate the next era of space exploration, NASA in some ways transformed the Apollo achievement into physical objects that fit smoothly with a concept we were predisposed to associate with national pride in the first place: the ship. In this case, a spaceship. As the shuttle took its place as an iconic American symbol, the limitless challenges of space offered a new alternative for the sea as venue and a metaphor for our challenges and boldest ambitions. The oceans, while always demanding respect, seemed increasingly manageable in an age of supertankers and nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. Soon, images of the shuttle lifting off became as commonplace as those from the Apollo era as representations of American achievement.

It was not long, however, before space, like the sea, reminded us that lack of respect demands a very high price. The loss of Challenger in January 1986 shook the United States as few events could, and indeed it would not be until 9/11 that the deliberate destruction of an entirely different American symbol struck the nation with similar intensity. Human nature and experience remind us that it is often through loss that we fully understand and appreciate what we have, and it is this, too, which gives the concept of the ship its place. It is precisely because ships are sometimes lost that we find them to be a reflection of our own circumstances. In addition to the mundane political and practical reasons for the shuttle’s long career, it seems possible that because the orbiters tapped deep into the cultural phenomenon that is the enduring appeal of the ship, we persevered even as ships were lost.

It was not until the Space Shuttle era, however, that the craft we built even began to approach the popular image of what a spaceship should look like. In comparison with what came before it, and apparently what is to come after—capsules both—one could look at a shuttle and see it exudes those elements of “shipness” which are instantly apparent. As one-use items, even when that use was carrying astronauts to the Moon, very little of the Apollo configuration matched the expression. In fact, to the casual observer, it was difficult to tell where the launch vehicle ended and the spacecraft began. As for a mission’s end—capsules parachuting into the ocean—it appeared as glorified ejection seats, the minimal remains of what was once something much greater that has now disintegrated.

| Just because space allows for an ugly design does not mean that it should be so indulged. Creating a craft one can love may go a long way to creating spaceships that the public indeed does love, as much, perhaps, as they loved the Space Shuttle. |

By contrast, the configuration of the Space Shuttle system served to emphasize its very different nature. The winged craft perched as it was on the back of external tank, almost ethereal and quite distinct from that of the rest of the stack. Once free of Earth, whether docked to the International Space station or photographed floating against the backdrop of a planet 70 percent water, the shuttle presented itself in a manner which clearly belonged to the future but also echoed the past. Even upon landing, as it assumed the obvious image of an aircraft, the shuttle still appeared to be what it was: a spaceship. Ultimately, if the ship as metaphor has any applicability to the Space Shuttle, then one cannot avoid considering the fact that as a vessel to give passage to our boldest ambitions, ongoing exploration, and an expanding human presence in space, it may have fallen short, but it looked damn good doing it.

In looking to the future, it may be relevant to consider the question of why, despite its well-documented flaws and exorbitant costs, the shuttle held such a strong appeal for so many years in the light of what it means be a ship, and why that is still important to Americans. Perhaps it may also explain the reluctant acceptance of capsules as immediate successors, and why some have come to regard the mothballing of the shuttle fleet with no clear successor as definitive evidence of an America in decline.

For the moment at least, the future is the past, as three capsules and one space plane compete to take over one of the shuttle’s primary jobs, ferrying astronauts to ISS. As for deeper space, NASA’s awkwardly named Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV) lacks, among other things, a launch vehicle and a compelling destination. Assuming, however, the darkest predictions of an American retreat from space exploration are overblown, and a definitive program eventually emerges based on the current configuration, it may prove difficult to garner the support enjoyed by the shuttle, in part because it does not appear to advance the state of the art beyond the level of the shuttle as successor spaceship.

To some extent, this may be unfair. Craft built for space are naturally very different in design from those that ply the boundary between Earth and space. Absent the requirement of an aerodynamic shape, designers are free to suit whatever their particular needs may be; there is no greater example than the ungainly, buglike, Apollo lunar lander. However, just because space allows for an ugly design does not mean that it should be so indulged. Creating a craft one can love may go a long way to creating spaceships that the public indeed does love, as much, perhaps, as they loved the Space Shuttle.

| It is by no accident that Virgin Galactic’s initial tourist craft, VSS Enterprise, while strictly suborbital, bears the name more people have come to associate with spaceships than any other. I suspect it will not be the last. |

Aesthetics cannot trump economics, and to be sure, a lack of “shipness” has not prevented the Soyuz from a long and distinguished history. After all, a ship assumes its status not because of how it looks but because of what it does. One suspects that if a truly ambitious concept such as appears the Nautilus-X were to suddenly appear in orbit, we would quickly find a way to love it. For the moment, however, it seems that beyond low Earth orbit, the foreseeable future will only offer competing variations of capsules, like Dragon versus Orion. In that case, it may come down to subtle differences such as naming the individual craft, highlighting their flexibility for different missions, and emphasizing the all-important aspect of at least partial reusability to persuade an otherwise disaffected public that its spacecraft are indeed worthy of the moniker “ship”. National economics indicate that developing and maintaining support for a new program of meaningful space exploration will be hard—perhaps much harder than we think—and in the long run the vessels we build to traverse it may require the kind of emotional investment that goes beyond rational decision cost-benefit analysis, the kind that we sometimes attach to ships and the other things we love. Not logical, perhaps, but given what passes for space policy these days, what really is?

Whether or not the shuttle was a good ship, or was even a true spaceship, is not as relevant as the fact that it represented something that people intuitively understood. They were the first. And if mankind finally leaves the environs of our solar system and spreads out into the stars, the ships that carry us into the depths of space will trace their lineage back to this first fleet, and inevitably our descendants will look back in envy that we had the good fortune to have been there at the beginning: Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, Endeavour, and one more, Enterprise, which never made it to space, but whose namesake continues to dominate our perception of what a spaceship should look like. It is by no accident that Virgin Galactic’s initial tourist craft, VSS Enterprise, while strictly suborbital, bears the name more people have come to associate with spaceships than any other. I suspect it will not be the last.