Big science in an era of tight budgetsby Jeff Foust

|

| “Whatever else it is, a large scientific lab is a public works project,” Weinberg explained. “It, therefore, will always get enthusiastic support from local politicians… and hostility, or at best apathy, from other legislators from other parts of the country.” |

One of the more pessimistic points of view about the future of big science came from someone outside of astronomy. Speaking at a special public session on the evening of January 9, Nobel laureate physicist Steven Weinberg of the University of Texas argued that it would be increasingly difficult for governments to support the next generation of major projects, be they observatories or particle accelerators.

In particle physics, Europe’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has achieved some major successes, including tantalizing hints of the existence of the Higgs boson. However, Weinberg said it was only a matter of time before the science the LHC could perform would be exhausted and physicists sought an even more powerful accelerator. When that time comes, though, he said he was skeptical even a coalition of governments would be willing to pay for it. “It’s going to be a very hard sell, and it may be impossible to get the next accelerator built,” he said.

His own pessimism is rooted in his experience two decades ago with the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC), a large particle accelerator that was under construction outside Dallas when Congress killed the project in 1993. The project was ostensibly canceled because of its growing cost, but Weinberg argued the SSC had an “undeserved reputation” for cost overruns. “Most of the cost increase of the Super Collider was caused by the fact that Congress never funded the project according to the original profile,” he said. “As you stretch out a project, it gets more expensive.”

The SSC, he said, had a limited constituency in Congress, which made it difficult to win funding. “Whatever else it is, a large scientific lab is a public works project,” Weinberg explained. “It, therefore, will always get enthusiastic support from local politicians, as it [the SSC] did in Texas, and hostility, or at best apathy, from other legislators from other parts of the country.” He recalled being courted by one unnamed member of Congress from upstate New York, hoping that the project would select a site in the Adirondacks; when the SSC instead decided on Texas, that member became a vociferous opponent of the project.

Weinberg also blamed human spaceflight, in particular the International Space Station (ISS), for the SSC’s ultimate downfall. Both programs were threatened with cancellation in 1993, but the Clinton Administration chose to actively support only the ISS, leaving the SSC to fend for itself, which he saw as a setback for science in general. “All of the great discoveries that have made such great progress in cosmology in particular have been from unmanned observatories,” he said. “The International Space Station was sold as a scientific laboratory, but nothing interesting has come from it.”

The SSC made its own errors that contributed to its cancellation, though, he admitted. It originally relied too much on a single political patron, then-Speaker of the House Jim Wright of Texas, who was forced to resign from Congress in 1989 after an ethics scandal. Weinberg added that the project didn’t do enough political outreach, focusing its efforts on the Senate rather than the House; it was the House that led the effort to eventually kill the program.

Those issues, along with competition for funding elsewhere in science (another issue that hurt the SSC), remain today. “All of these problems are going to come up again when we go to our governments for the next big accelerator,” he said.

| “We may see in the next decade or so an end to the search for the laws of nature which will not be resumed again in our own lifetimes,” Weinberg warned. |

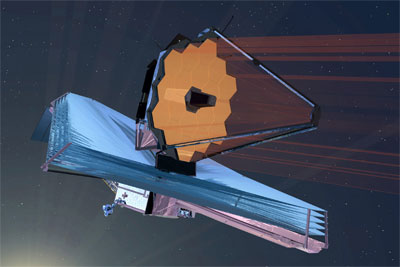

Weinberg said he sees parallels between the SSC 20 years ago and JWST today. “Its history is somewhat reminiscent of the SSC,” he said. “It’s facing accusations of overspending, but the problem again is that at the funding levels being requested, it’s being stretched out to the point where it’s getting more and more expensive.” He cautioned that the JWST, like the SSC, may also be relying too much a single, if powerful, supporter in Congress, namely Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-MD).

The current support for JWST comes at a price, Weinberg argued. “The rest of astrophysics at NASA, including cosmology, is being starved,” he said. That situation will only get worse with the threat of so-called “sequestration”, the across-the-board budget cuts looming for federal programs in the wake of last fall’s failure by a joint Congressional committee to come up with a long-term deficit reduction plan. “It’s going to be very hard for any kind of science, let alone big science,” in that kind of environment, he said.

That means the progress being made in particle physics and astronomy alike could be coming to at least a temporary end soon as governments become unable or unwilling to fund the next generation of accelerators and telescopes. “We may see in the next decade or so an end to the search for the laws of nature which will not be resumed again in our own lifetimes,” he warned.

JWST supporters look ahead

While Weinberg was pessimistic about the future of big science and concerned about the fate of the JWST in particular, NASA officials and others involved with the space telescope expressed renewed optimism about the project after surviving the events of the last year.

“About a year ago, I didn’t know we would be having this town hall this year,” Eric Smith, deputy program director for JWST, said January 9 at a town hall meeting devoted to JWST at the AAS conference. That was because of the uncertainty about the telescope’s future at that time. “We are here this year, so I’m very optimistic” about the program’s future.

His optimism, he said, is based on the funding the program received for the current fiscal year—$530 million—as well as the technical progress it has made, meeting all its milestones planned for the last year. With the “replan” of the JWST completed, Smith said it was up to the program team to implement that new plan. “The main challenge for the program this year is to more or less ‘walk the walk,’” he said. “We have to perform to keep things on schedule.”

At a more general NASA town hall meeting two days later at the AAS conference, space agency officials made similar points. “The James Webb Space Telescope is one of the primary goals of NASA, and one of its highest priorities,” alongside utilization of the ISS and development of the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket and Multi Purpose Crew Vehicle, said new NASA associate administrator for science John Grunsfeld. “That means astrophysics is very important to NASA, and we should all be happy about that.”

Grunsfeld was upbeat about the JWST replan. “We’ve got a really good plan going forward,” he said. “I really do feel that we have a good handle on the programmatics and the science system engineering.”

He acknowledged, though, that the program went through a tough experience last year with the replan and the threatened defunding by Congress. “It was real drama,” he said of the effort to win funding for the telescope, thanking AAS members for their Congressional lobbying efforts, which he called “a loud and clear voice about basic science research.”

| Grunsfeld warned the scientific community not to engage in internecine battles among one another as budgets tighten. “We are only as strong as our whole, and if we pit community against community, everybody loses.” |

Grunsfeld, on the job less than a week at the time of the town hall meeting, said his new job would not be an easy one. “One could say accepting the role of associate administrator at NASA is slightly crazy, and I certainly think it’s higher risk than anything I’ve ever done before,” said the former astronaut who flew on five shuttle missions, including three to service the Hubble Space Telescope. He told the astronomers who packed the ballroom for the hour-long session that “I do feel the full weight and responsibility of carrying an enormous science program to help enable all of you to be great scientists. My job is to help all of you to change the world.”

Those challenges come in part from the “constrained” budgets NASA’s science programs face. Grunsfeld said he planned to work with his counterpart at NASA’s human spaceflight directorate, Bill Gerstenmaier, to “see what synergies we have,” including the potential use of the SLS to launch flagship-class science missions in the future. Other efforts at NASA outside the science directorate could also benefit its programs, including the development of lower-cost launch vehicles like the Falcon 9 as well as the use of the ISS as a platform for demonstrating technologies that could then be used on science missions.

He warned the scientific community not to engage in internecine battles among one another as budgets tighten. “We are only as strong as our whole, and if we pit community against community, everybody loses,” he said. Similarly, he said that squabbles between the science and human spaceflight communities were also ill-advised. “One of the reasons I’m in this job now is that administrator Charlie Bolden believed that teaming with human spaceflight on those things that make sense… makes the whole program stronger.”

Some of the fiscal details of the JWST replan, including what science programs at NASA will lose money to help cover the increased cost of the space telescope, have yet to be announced, and will probably wait until the release of the fiscal year 2013 budget proposal in February. NASA officials previously said, and confirmed at the AAS meeting, that half of the additional costs would come from the agency’s astrophysics, heliophysics, and planetary sciences programs, with NASA’s Cross-Agency Support account paying for the other half.

The JWST did get an endorsement at the meeting from one member of Congress. “Contrary to what might have been written at the time, Congress supports the James Webb Space Telescope,” said Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX), in a brief, unannounced speech at the AAS conference on January 12. Smith was referring to the decision by House appropriators not to fund the JWST last summer. Smith explained that was an effort by Rep. Frank Wolf (R-VA), the chairman of the appropriations subcommittee with oversight of NASA, to gain the White House’s attention to the telescope’s problems.

Smith, who serves on the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee, said the criticism by the committee’s leadership of the administration’s human spaceflight plans should not be taken to mean that Congress is broadly opposed to NASA or other agencies’ scientific efforts. “I hope that the broad science community does not translate such criticism of NASA’s programs into a perception that arguments between Congress and the administration mean that somehow Congress is anti-science,” he said.

Winning public support for big science

But can that professed support for science and NASA be translated into something more concrete—dollars—when it’s time for Congress to make the hard decisions about budget priorities later this year and beyond? It may require the scientific community, and its advocates, to redouble their outreach efforts to politicians and the general public alike.

“We learned the lessons of the Superconducting Super Collider that, if we’re going to be relevant, that if we’re going to have our projects succeed at any scale, we have to tell the story of why our science is important,” Grunsfeld said. He recalled that, at an AAS meeting two years ago in Washington, NASA administrator Bolden told astronomers to go speak to their communities about astronomy, a charge Grunsfeld reiterated. “We’re on the front lines. We’re the ones doing the really exciting stuff.”

| “The tactic of leading with a great picture is a good one, but I think if we were to stop at that point, over time people would get habituated to it,” Leshner said. |

The need for broader public outreach is not limited to astronomy alone. “There has been, particularly over the last few decades, substantial tension between science and the rest of society,” said Alan Leshner, CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), in a plenary talk at the AAS meeting January 12. “I have never, in my adult scientific lifetime, experienced a level of tension that we’ve experienced over the last couple of decades.”

Much of that tension stems from research outside of astronomy, from biomedical work to climate change. Leshner, a neuroscientist, said he was a bit envious of the attention that astronomy gets. “I am really jealous about how much people love astronomy,” he said. “People like brains, but somehow they seem to love the planets and the stars and the skies.”

Leshner warned, though, that the public’s love of astronomy, in particular the stunning imagery that telescopes and spacecraft provide, is insufficient. “The tactic of leading with a great picture is a good one, but I think if we were to stop at that point, over time people would get habituated to it,” he said. “I really do think that the people who fund astronomy know it’s more than just cool,” citing spinoffs that have been “tremendously useful” to society both economically and culturally.

That’s the challenge facing astronomy and other space sciences today. JWST and other large-scale projects to study the solar system and the universe have clear and important scientific rationales and even philosophical justifications, helping answer questions as basic as “where did we come from?” and “are we alone?” But, in an era where budgets are tightening, those questions run the risk of seeming like luxuries compared to other scientific endeavors that offer more near-term, practical benefits, such as medicine and biotechnology.

“I think the more enlightened policymakers understand that you won’t see the benefits immediately, but you’ll see it in the longer term,” Leshner said of astronomy research. In the current political environment, though, particularly one exacerbated by the hyperpartisan politics of an election year, enlightened policymakers can seem to be few and far between. The continued progress of astronomy, dependent as it is on a number of large ground- and space-based observatories, is far from guaranteed.