Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251 three years later: where are we now?by Michael Listner

|

| Even though the incident could not be resolved under the Liability Convention and international law in general, there were still positive outcomes. |

After the initial shock of the collision subsided, the finger-pointing between the operators of the satellites in the United States and Russia began. Russia was quick to point out that Cosmos 2251 was a derelict satellite incapable of maneuvering, and it placed fault for the incident on Iridium LLC’s failure to maneuver their spacecraft so as to avoid the collision. Russia also correctly asserted that it did not have an obligation under international law to dispose of Cosmos 2251 after it became derelict. For its part, Iridium LLC contended that it did not have an obligation to avoid the collision even if was aware that such a collision would occur.

The collision opened the possibility that second scenario of the Liability Convention would be invoked for the first time to recover compensation for the loss of either satellites. Under the second scenario of the Liability Convention, a fault liability standard applies whereby a state will be considered liable only if it can be shown that the damage caused was due to the fault of the state or states responsible for the launch of the space object, as the case may be.1 This theory of liability is similar to the maritime law standard of comparative fault, whereby the percentage of fault and thus liability will be apportioned according to the negligence of each party involved to the aggregate liability. Once the percentage of fault for each party is determined, the total amount of damages for the incident will be determined, and from that total each party will be apportioned its damages based on its percentage of fault. However, the conflicting information leading up to the crash, coupled with the lack of tracking data for that region of Earth orbit, gave neither party sufficient evidence to meet the fault standard set by the second scenario.

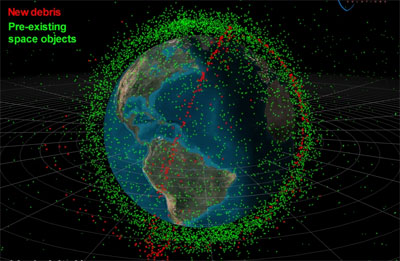

Even though the incident could not be resolved under the Liability Convention and international law in general, there were still positive outcomes. First, the collision brought the topic of orbital space debris and space situational awareness to the forefront and made the general public aware of the issue. While awareness in of itself is not curative, it did give the issue much needed attention and was helpful to motivate actors who were otherwise complacent about orbital space debris and space situational awareness in general to reconsider the issue and take steps to address it.

| If we remember anything on this anniversary of the collision between Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251, it should be that the problem cannot be wished away and ignoring it will ensure that another, perhaps more serious, incident will occur in the future. |

The incident also provided incentive for more cooperation between spacefaring nations to address the issue. After the collision, the United States and Russia opened a dialogue to discuss the incident and take measures to prevent similar incidents in the future. The most notable example of this cooperation is an agreement between Russia and the United States via US STRATCOM’s Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC). Under this agreement, JSpOC shares orbital element data it obtains with Russia as well as other governmental and nongovernmental organizations. This relationship was exemplified when the JSpOC provided Roscosmos with orbital element and predictive data on its marooned probe Phobos-Grunt.2 It is noteworthy that the arrangement JSpOC currently has with Russia and other countries was in the works prior to the Iridium/Cosmos collision; however, the collision epitomized the need for this cooperation and certainly influenced its offering.

In spite of these beneficial outcomes, more still needs to be accomplished. The issue of space situational awareness needs to move forward so operators can better understand what is occurring in the space environment. Space debris requires attention as well: while many of the spacefaring nations have implemented guidelines to mitigate accumulation of additional space debris, a clear and present issue remains with the debris already present from decades of space activities. Regrettably, national security concerns, politics, legalities, and economics make both issues difficult to address. However, if we remember anything on this anniversary of the collision between Iridium 33 and Cosmos 2251, it should be that the problem cannot be wished away and ignoring it will ensure that another, perhaps more serious, incident will occur in the future.

Endnotes

1 The first scenario applies a strict liability standard whereby a State is considered strictly liable for any damage caused by a space object launched even in the face of circumstances that are outside a its control. Under this standard, if more than one State is responsible for the launch of the space object in question then that State will be held joint and severally liable for any damage caused. The first scenario of the Liability Convention was invoked by Canada through diplomatic channels after the reentry and subsequent crash of the RORSAT Cosmos 954 on January 24, 1978 in the northwest territory of Canada and led to a settlement for the costs of the cleanup and damages.

2Michael Listner, Phobos-Grunt Highlights Cooperation in Space Situational Awareness, Space Safety Magazine, December 20, 2011.