Forever Marsby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Von Braun knew then that there were a number of important aspects of such a mission that he had left out of his book, including astronavigation (i.e. how to navigate to Mars) and the effects of spaceflight on the human body. |

Von Braun wrote that in the April 30, 1954, issue of Colliers magazine. His article was part of a classic series on spaceflight, well-regarded both for the articles themselves and the artwork that accompanied them. By his prediction, it would be 2054 or later before humans would be “ready” to undertake a mission to Mars.

By the time he wrote that, von Braun had put a lot of thought into the subject. In 1953 he published The Mars Project, a book he had originally written in German that discussed the technical requirements for a human mission to Mars. But he knew then that there were a number of important aspects of such a mission that he had left out of his book, including astronavigation (i.e. how to navigate to Mars) and the effects of spaceflight on the human body.

Eight years after his Colliers article, in the introduction to the reprinted edition of The Mars Project, von Braun was more optimistic than he had been in 1954:

“The logistic requirements for a large elaborate expedition to Mars,” I said in the introduction to the first edition, “are no greater than those for a minor military operation extending over a limited theater of war.” I am now ready to retract from this statement by saying that on the basis of technological advancements available or in sight in the year 1962, a large expedition to Mars will be possible in fifteen or twenty years at a cost which will be only a minute fraction of our yearly defense budget.”

| Many years later, David joked that the title did not say nineteen eighty-eight, so it could still come to pass. |

Von Braun then listed the technological advancements that had taken place in less than a decade. Although no robotic mission had been successfully launched to Mars by the time he wrote that, it was clear that the planetary navigation challenge was about to be solved. Still, to go from an estimate of 2054 to perhaps 1982 was quite a leap.

|

Other authors—or their editors—have gone farther and included the date of a Mars mission in the actual title of their book or article. In November 1979, esteemed space reporter Leonard David wrote an article for Future Life magazine titled “Mars in ’88”. It was the first article to mention the “Mars Underground” movement then emerging in Boulder, Colorado. The Mars Underground was a group of scientists, grad students, and enthusiasts frustrated that NASA seemed to be ignoring Mars after the Viking missions, and certainly was not discussing human missions to the red planet. They wanted to put that subject back on the agenda, and one way to do so was to talk about human missions to Mars as near-term possibilities, which they did at a series of conferences known as “The Case for Mars”.

Many years later, David joked that the title did not say nineteen eighty-eight, so it could still come to pass. The gist of his article was that a human mission to Mars might be possible in the same timetable as the Apollo program, assuming that the United States started soon. We didn’t.

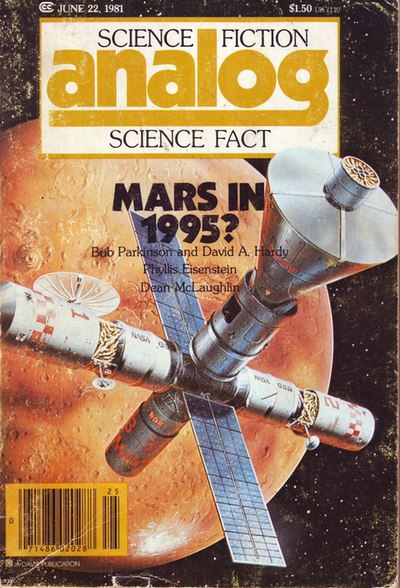

The June 22, 1981, issue of Analog magazine ran a cover story about a human Mars mission by Bob Parkinson. Notably, while the cover asked “Mars in 1995?”, the article was more adamant: “Mars in 1995!” Parkinson’s article was ably illustrated by David A. Hardy. It detailed an international Mars mission using hardware that was then already under construction for the Space Shuttle program, particularly ESA’s Spacelab module. With some of the hardware already becoming available, the Mars goal seemed to be more within reach than it had only a few years earlier.

|

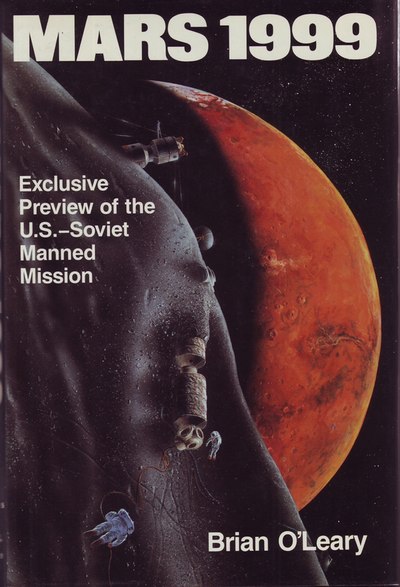

In 1987, Brian O’Leary published Mars 1999, from Stackpole Books, which purported to provide an “Exclusive preview of the U.S.-Soviet Manned Mission.” You can see a big problem in his subheading: the Soviet Union ceased to exist only a few years after the book was published. O’Leary was a noted astronaut dropout from the Apollo program who wrote some interesting articles as well as several books, but later developed a reputation for being somewhat weird. Mars 1999 proposed a mission to one or more of the Martian moons, an idea that has been around for a number of decades—and has some merit. The primary benefit is that the mission does not require development of a lander craft. It would be an interim step to an eventual landing, sort of how the Apollo 8 and 10 missions demonstrated the hardware prior to the first landing attempt.

O’Leary’s book really stems from a different origin than the earlier articles. It was obviously inspired by Carl Sagan’s advocacy of a joint US-Soviet Mars mission. And it was almost certainly influenced by the 1985 publication of The Mars One Crew Manual, a book that purported to be exactly what its name implied: a manual for crewmembers of the first human mission to Mars. (As a sidenote: The Mars One Crew Manual was a follow-on to The Space Shuttle Operator’s Manual, which had clearly been inspired by the bestselling Star Fleet Technical Manual of the mid-1970s—yet another example of Star Trek’s once substantial influence on Americans’ enthusiasm for spaceflight.)

Although there were a number of notable Mars novels published during the 1990s such as Kim Stanley Robinson’s trilogy that started with Red Mars, and Robert Zubrin published his nonfiction book The Case For Mars in 1996, there do not appear to have been any books or articles that included an actual date in the title. But in 2011, Dave Ketchledge published 2033 The Nuclear Mission to Mars. Although I do not have a copy, the book is apparently about using nuclear thermal propulsion for a Mars mission a couple of decades from now. At over 600 pages it is not exactly light reading.

|

Putting a date in the title of a book or magazine article is not really a prediction, so it’s not fair to poke fun at authors because we did not send humans to Mars in 1988, 1995, or 1999 (although we still do have a shot at 2033). These dates are better understood as marketing rather than prognostication. They’re intended to be provocative, to change the discussion of a future Mars mission from the realm of science fiction to something that can be achieved within an amount of time that can be grasped by just about anyone.

The Mars works cited above, however, were speculative, but based heavily upon existing technology. Writing about near-term space goals and including a date when they can be achieved is predicated upon the hope that maybe, just maybe, that will help make it come to pass.

| But here’s one of the ironies: the more we study something, the more the earliest possible date for a Mars mission might actually recede. |

So when can humans reach Mars? Of all the writers discussed above, von Braun is probably the one who put the most educated (i.e. technically trained) thought into it, and when he wrote he was not advocating, he was speculating. But he was also speculating based upon much less data than the later writers. Von Braun’s first prediction of the middle of the 21st century still seems reasonable today. We could possibly try it earlier, but anybody who has looked into the subject realizes that there is substantial risk due to a great many unknowns. Buying down that risk may require another four decades of research, especially if we have no active plans to extensively research many of the key issues of human physiology necessary for such a mission, and no active plans to develop the technologies required.

It would be comforting to think that with all our experience with spaceflight—such as ten years of continuous operations of a space station and all that accumulated knowledge of how often things break down in space and how the human body responds in space—we have a better handle on this question today than we did two, three, certainly five decades ago.

But here’s one of the ironies: the more we study something, the more the earliest possible date for a Mars mission might actually recede. We can make overly optimistic predictions based upon ignorance, but the accumulation of data might result in us realizing just how tough the problems are, and how much longer it might take to solve them. A good example is the issue of papilledema in astronauts. Papilledema is a swelling in the optical disk that results in blurred vision, sometimes permanently. This phenomenon was essentially unrecognized in human spaceflight until the past decade, and in recent years it has become a major issue for long-duration astronaut missions. It is possible that after a lengthy journey to Mars, at least some of the crew (so far the effect is most notable in males) could arrive at the Red Planet with severely degraded eyesight. It could be that this medical condition may require an effective solution before any human Mars mission can take place. There are no ophthalmologists on Mars. It is yet another example of learning something that could be a showstopper for the mission to Mars.

However, there’s another, much bigger problem: even if we could work out a reasonable timeline based upon these technical and physiological questions, the fundamental fact remains that such a mission is a political act, and nobody is good at predicting political outcomes even months from now, let alone decades (witness the Republican primaries). Thus, “when could we do it?” might be equally as useless a question as “when will we do it?”

Unfortunately, for far too long we’ve had to wait, and it looks like von Braun’s first prediction may still be the most accurate one.