Planetary Resources believes asteroid mining has come of ageby Jeff Foust

|

| “The ability to use space resources to help explore space is a missing piece” for the future of space exploration and commercialization, Anderson said. |

That “new paradigm for resource utilization” means taking a fresh look at what may be the most valuable resources on asteroids. In the past the interest in asteroids has been in precious and other metals they contain: gold, platinum, and related metals. Clearly valuable, these metals had many applications on Earth and in space. However, Planetary Resources is instead initially going after something that is plentiful on Earth but potentially even more valuable than metals in space: volatile compounds, particularly water ice.

The company’s founders see water ice derived from asteroids, rather than hauled up from Earth, as key to lowering the costs and thus enabling more government and commercial space activities. “Over the next five to ten years, considerable capability will be added in terms of launch vehicles and spacecraft,” company co-founder and co-chairman Eric Anderson said in a telephone interview prior to the company’s press conference, referring to the development of new launch vehicles and spacecraft. “The ability to use space resources to help explore space is a missing piece.”

Anderson said that he believes that Planetary Resources can deliver water to propellant depots in Earth orbit or elsewhere in cislunar space, like the various Earth-Moon Lagrange points, for a fraction of the cost of hauling it up from Earth. Launching a kilogram of propellant to a Lagrange point, he said, costs as much as $100,000 per kilogram. “If we were able to provide that propellant for a price of one-tenth of the effective cost of bringing it from the Earth, that would shave off a large portion of the cost of going into deep space,” he said.

The company has a three-step approach to accomplishing this. Initially, Planetary Resources will launch small spacecraft into Earth orbit to observe near Earth asteroids, looking for ones that appear to be the most promising in terms of ice and other resource content. The company will then follow up those observations with prospecting missions to collect more precise data in situ. Finally, the company will send missions to harvest those resources and return them to those propellant depots near the Earth.

At Tuesday’s press conference, Anderson shied away from giving specific schedules for when that third phase—resource extraction and return to Earth—would take place. “We do come from the Burt Rutan school of trying to avoid giving out timelines,” Anderson said. The company’s other co-founder, Peter Diamandis, said that after flying those initial Earth orbit missions within the next two years, it would follow up with the second phase of prospecting missions a few years after that. “Ultimately, our goal is to hopefully identify the first asteroid to prospect within the decade,” Diamandis said.

| “In a lot of ways, what we’re focused on at Planetary Resources is doing the same for robotic exploration” that SpaceShipOne did for human spaceflight, said Lewicki: demonstrate the capabilities that once belonged only to governments are now in the reach of small teams. |

In the earlier phone interview, though, Anderson offered a more specific, and aggressive, timeline. “I think we’ll have propellant depots in operation within the decade, so, before 2020 we will have propellant depots operating using extraterrestrial resources,” he said. He added the company hadn’t decided if it would own and operate its own depots, or instead serve as a supplier for someone else’s depots.

The company is also interested in mining asteroids for platinum-group and other precious metals, but only after it gets experience from accessing asteroids for ice. “I’m certainly not shying away from emphasizing that, but it’s a less urgent example,” Anderson said, arguing that “certainly within 20 years” there will be a strong, positive case for extracting such metals from asteroids. “I think the near-term driver for the space resources market is volatiles from near Earth objects” for refueling spacecraft and supporting robotic and human exploration beyond low Earth orbit, he said.

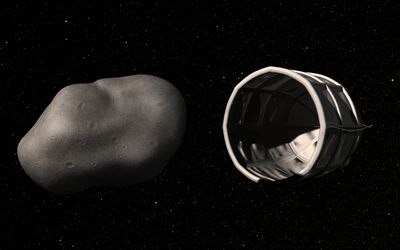

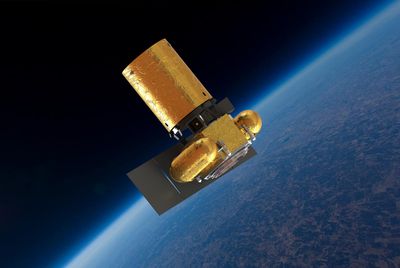

Planetary Resources’ first spacecraft, Arkyd-101, will operate in Earth orbit, surveying near Earth asteroids to identify candidates for later missions. (credit: Planetary Resources) |

An “inflection point” for commercial space

Planetary Resources is not the first company to consider asteroid mining. A decade and a half ago, entrepreneur Jim Benson established SpaceDev with an initial intent of sending a spacecraft to a near Earth asteroid to study what resources could be potentially extracted from it, while also making a private claim on that asteroid. SpaceDev never built the Near Earth Asteroid Prospector, though, and the company’s interest soon turned to other smallsat missions and hybrid rocket motor development.

This time, Anderson said, the space industry had matured to the point where asteroid mining was more feasible. “We’re at an inflection point for commercial space,” he said, citing the developments by companies ranging from SpaceX to Bigelow Aerospace. These companies, along with government exploration plans, like NASA’s goal of mounting a human expedition to a near Earth asteroid by 2025, create demand for space resources that help support Planetary Resources’ business case.

At the press conference, Diamandis said there are five “critical elements” that made today the right time to begin work on asteroid mining. The first, he said, was the development of “exponentially growing technologies” that enable small teams to do what previously required major government programs. One example they cited was SpaceShipOne, which Scaled Composites developed in the early 2000s for less than $30 million for suborbital human spaceflight, something that four decades earlier required the resources—and budget—of NASA.

“In a lot of ways, what we’re focused on at Planetary Resources is doing the same for robotic exploration,” said Chris Lewicki, president of Planetary Resources, in an interview before the press conference. “We’re putting forth missions like the Mariners and Rangers and Surveyors of the ’60s.” Now, though, he added, the technologies make such missions possible for a commercial company.

That philosophy is evident in the company’s initial spacecraft, called the Arkyd-101. (Prior to Tuesday’s announcement, Planetary Resources worked in stealth mode as Arkyd Astronautics; the name is reportedly derived from Arakyd Industries, a company from the Star Wars universe.) Weighing only 20 kilograms and fitting into a box 40 centimeters on a side, Arkyd-101 is a spacecraft fitted around a telescope that will be used for observing asteroids.

That telescope can also be used as part of an optical, or laser, communications system that the company says will enable high-bandwidth communications at low power levels. Under the Arkyd Astronautics name, the company received a $125,000 Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) award from NASA in 2011 for work on “Multi-functional Optical Subsystem Enabling Laser Communication on Small Satellites”.

| “We’re seeing a new generation of centamillionaires and billionaires who are now investing in space,” Diamandis said. “This is smart money investing in one of the largest commercial opportunities ever: going to space to gain resources for the benefit of humanity.” |

The second key factor enabling Planetary Resources, said Diamandis, is the availability of commercial space launch. That initial mission, planned for launch within 24 months, would fly as a secondary payload on another, as yet unidentified vehicle. That approach, which lowers launch costs over buying a dedicated launch, may also be used for the second phase of missions, when Planetary Resources will send swarms of Arkyd 200-series spacecraft to asteroids, networked together to provide additional capabilities and redundancy.

The third factor, Diamandis said, is what he called “a new generation of risk-tolerant investors” willing to put their money on space projects despite their long timelines for financial return and the high risks of failure. “We’re seeing a new generation of centamillionaires and billionaires who are now investing in space,” he said. “This is smart money investing in one of the largest commercial opportunities ever: going to space to gain resources for the benefit of humanity.”

Planetary Resources has lined up an all-star list of investors, including Larry Page and Eric Schmidt, the CEO and executive chairman, respectively, of Google; Ross Perot Jr., chairman of the Perot Group; and Charles Simonyi, the former Microsoft executive who flew to space twice as a customer of Space Adventures, another company established by Anderson and Diamandis. Company officials declined to say how much those and other investors have put into the company so far.

“I really believe in the team,” Perot said, patched in by phone to the press conference. “I’m a big believe in the privatization of space, commercial space. It really is the next great industry in our nation.”

“It does remind me of the early days of the personal computer world,” Simonyi said of Planetary Resources’ plans. “Being able to bring a billion tons of water at once and making it accessible, that would completely change the situation.”

The final two reasons for Planetary Resources, Diamandis said, was the “resource pinch” society was facing and being aligned with NASA’s exploration plans and its increased emphasis on relying on commercial providers. On the former point, Diamandis mentioned his recent book Abundance, which describes how technology can help make scarce resources abundant. (The book, though, doesn’t specifically mention asteroid mining at all, and only makes tangential references to space in the text.)

Another reason not specifically enumerated by Diamandis but brought up by company officials is the emphasis on small, highly-motivated teams of employees to work on projects, and by extension keep labor costs down. Planetary Resources has about two dozen engineers on staff, Anderson said, and its workforce would be unlikely to grow into the hundreds. The company is hiring for some technical positions now; the company posted a job application form on its web site that attracted nearly 1,000 applications in less than 48 hours.

The company already has on board a number of experienced people from JPL to help develop its spacecraft. Lewicki himself worked on the Mars Exploration Rovers and the Phoenix Mars Lander. “We have many people on my team that I brought from JPL who were as excited about the opportunity as I was that they jumped ship from Mars Science Laboratory and other exciting projects to really redefine the way robotic space exploration can be done,” he said.

Obstacles and risks

Despite all those attributes, the idea that a company can profitably mount missions to prospect and mine asteroids has raised more than a few skeptical eyebrows in the space community. They’re skeptical about a variety of issues, from the business model to the technology to the legal questions surrounding use of extraterrestrial resources.

“There are so many huge hurdles they have to overcome,” sand Henry Hertzfeld, a professor at George Washington University who has studied space markets and economics. “Technically, could they do it? I have no doubt. But once you start factoring in the risks, the markets, and the legal hurdles, you can easily build a contrasting case where it makes no sense at all.”

Hertzfeld notes that there’s been a long history of new markets promised for spaceflight, from the “smokestacks in the sky” vision of space manufacturing in the 1960s and 1970s to more recent plans for low Earth orbit communications satellite networks and space tourism. These efforts either failed or have been significantly delayed. All required large numbers of launches to be successful, a challenge given the current state of space transportation and a potential concern for asteroid mining as well.

| “When failure is not an option, success gets really expensive,” Lewicki said. “We will live with, and learn from, our failures.” |

Exactly how many launches will be required for asteroid mining and fuel depots is unclear, and Planetary Resources has also been vague about the technologies it will use for those later resource extraction missions, saying it’s focusing for now on the earlier stages of Earth orbiting and prospecting missions. A study performed last year by Caltech’s Keck Institute for Space Studies analyzed the issue of asteroid retrieval and found it would be possible to capture a very small (approximately 500-ton) near Earth asteroid and bring it to Earth orbit for about $2.6 billion. The study’s participants included Lewicki as well as Tom Jones, a former astronaut and advocate of near Earth asteroid exploration who is an advisor to Planetary Resources.

Utilizing asteroid resources poses legal challenges as well. The ability of a private company to acquire and sell ices, metals, or other resources obtained from asteroids falls into a legal gray area. Countries cannot claim asteroids or other celestial bodies under the widely-accepted Outer Space Treaty of 1967, but is silent on private property rights. The Moon Treaty prevents any public or private claims, but has been ratified by only a handful of countries, leading to a new push for a private property rights regime (see “Staking a claim on the Moon”, The Space Review, April 9, 2012).

In this case, said Franz von der Dunk, a professor of space law at the University of Nebraska, it’s unclear how both public and private interests can be protected. “Consequently, there is no legal certainty that those activities would not become seriously challenged,” he said in a university release. Those concerns include both the protection of the company from intrusion by others, as well as who would be liable for any damages caused by mining activities.

There’s also the question of whether the company can be financially viable, particularly since it will take until at least 2020 for it to start selling ice or other resources from or to propellant depots. Planetary Resources officials shied away from giving any specific financial details. “The company is cash-flow positive at this point,” said Diamandis. “We have a number of contracts with various companies and with some government organizations that are aligned with our technology roadmap,” Anderson added. That includes the STTR the company has from NASA to develop optical communications technology.

Long before it extracts its first gram of ice from an asteroid, though, the company sees additional sources of revenue from selling spacecraft to other customers for earth observation or other applications. “We, Planetary Resources, will use this capability to look out to the asteroids,” Lewicki said. “But it will also be used to look back to ourselves, here on Earth.”

Both the company and its investors were cognizant of both the technical and business risks involved in the company. Lewicki noted that one reason to go with the “swarm” approach of sending multiple spacecraft to a single asteroid is to provide risk tolerance should one spacecraft fail. “We know this is hard. We know we’re not always going to succeed,” he said. That willingness to accept failure can keep costs down. “When failure is not an option, success gets really expensive,” he said. “We will live with, and learn from, our failures.”

Simonyi said he knew this was a risky investment, and not for everyone. “If I knew my friend and neighbor was mortgaging his home to invest in the company, I would have advised against that,” he said. (One of the hurdles SpaceDev ran into with its asteroid prospecting plans was the Securities and Exchange Commission, who in 1998 alleged that the company was making false and misleading statements about its plans and projected revenues to potential purchasers of its stock.)

Anderson said that the other investors were also approaching this with their eyes wide open the risks and timelines the company faces. “We know there’s a significant probability that we may fail,” he said. “Of course we’re interested in making money. If we’re successful we hope to make a lot of money. But we understand that’s not going to happen overnight.”

“For me, it’s just really exciting,” Lewicki said. “It’s just the promise and the hope that we’re actually gotten to a time and place where private resources and technology, and the foundation that NASA has laid,” can enable such an effort. “We are taking what is that first, necessary step.”