R is for Rocket, S is for Spaceby Andre Bormanis

|

| Bradbury was often dismissed, if not outright ridiculed, by mainstream writers, but quickly learned to ignore his critics. If they didn’t think rockets and dinosaurs were suitable subjects for literature, to hell with them. |

He graduated from high school near the height of the Great Depression. His father had trouble finding steady work, and couldn’t afford to send his precocious son to college. So Ray spent three days a week in the Los Angeles public library, making it his personal university. In retrospect, he was grateful that his imagination had never been shackled by the chains of conventional thinking that “institutes of higher learning” often forge. He was fond of quoting Mark Twain: Never let college get in the way of a good education.

When Ray started out, the field of science fiction lacked respectability, to say the least. It was the province of the pulps: magazines printed on cheap paper, with lurid covers designed to catch the attention of immature boys. He was often dismissed, if not outright ridiculed, by mainstream writers, but quickly learned to ignore his critics. If they didn’t think rockets and dinosaurs were suitable subjects for literature, to hell with them. Ray loved that stuff, along with Martians and witches and things that go bump in the night, so that’s what he wrote about. His unique imagination was harnessed within vivid, lyrical prose, and after the publication of The Martian Chronicles in 1950, the literary elite were forced to acknowledge a striking new talent.

As Ray’s stories became more widely published and read, they fueled the imaginations of millions of young people over several generations, many of whom went on to cite his influence as a major reason they became scientists and engineers. His stories practically shouted that it wasn’t just okay to dream of rockets and space travel, it was wonderful, mythic, imperative—the highest accomplishment the human race could aspire to.

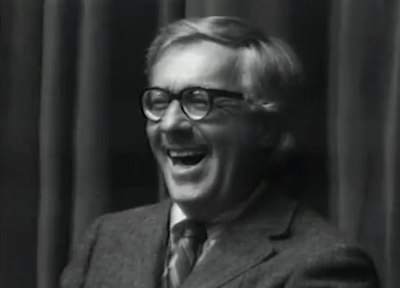

Like many people enthralled by astronomy and space travel, I grew up reading Ray’s stories. I had the great good fortune to spend time with him on a number of occasions over the years, beginning in 1979 when Ray spoke at my undergrad alma mater, the University of Arizona. By some strange miracle I was elected to take Ray and his wife to dinner and introduce him for his talk. Minutes after I picked him up at his hotel, in true fan-boy fashion, I gushed on and on about how much I loved The Martian Chronicles. He was warm and gracious, and one of the few people at the time who encouraged me in my own writing. In later years, I had the privilege of helping him organize fundraisers for The Planetary Society, and attended many of the plays he produced here in Los Angeles. These were often low-budget affairs in theaters smaller than the walk-in closets of some Hollywood stars, but to Ray that never mattered. Everything he did he did for the sheer love of doing it.

| He shared with the best scientists a childlike sense of wonder, a belief in infinite possibilities, a joy in discovery undiluted by the jaded, mature sensibilities that constrain most so-called grown-ups. |

In recent years he lamented that the Apollo program was looking more and more like the end of mankind’s ventures into deep space, not the beginning. His poem “Abandon in Place” is an elegy for a decommissioned launch pad at Cape Canaveral, a metaphor for what he perceived as part of a more troubling, pervasive decay in the American spirit. How could this exceptional nation, a country that dreamed such big dreams and made them come true, turn away from the greatest adventure in the history of mankind?

And yet Ray was an irrepressible optimist. In his story The Toynbee Convector, a man fools the world into thinking he’s traveled a hundred years into the future, returning with “proof” that the world of tomorrow will be glorious. It was a hoax, but it inspired people to build the future he claimed to have seen. Believe in something strongly and deeply and passionately enough, and it shall come to pass.

Ray professed almost complete ignorance about science, and barring his seminal novel Fahrenheit 451, considered the majority of his work to be fantasy, not science fiction. And yet he shared with the best scientists a childlike sense of wonder, a belief in infinite possibilities, a joy in discovery undiluted by the jaded, mature sensibilities that constrain most so-called grown-ups.

This same sprit is evident in many of the NewSpace entrepreneurs who have been making headlines recently, most notably Elon Musk of SpaceX. Musk was inspired by science fiction at a tender age, and after co-founding PayPal, found himself with enough money to take a shot at making his space travel dreams a reality. Although he has a degree in physics, Musk is largely self-taught in astronautics. He didn’t know what he didn’t know, but he didn’t let what he didn’t know get in his way. Like Ray, he sought his own path. Most of the leaders of the aerospace establishment expected him to fail. But, like Ray, Musk didn’t listen to the people who told him he was crazy, wasting his time and money. And just a couple of weeks ago, as we all know, SpaceX made history.

One of Ray’s strongest influences, Jules Verne, said that what one man can imagine, another can create. Ray stoked countless imaginations, and it will be exciting to watch, in the coming years, what those minds create. I’m sad that Ray didn’t live to see humans walk on Mars, but he believed, with unshakeable conviction, that we will. And there can be no doubt that the men and women who someday explore the dusty hills and valleys of that lonely red planet will know the name Ray Bradbury.