What’s the purpose of a 21st century space agency?by Jeff Foust

|

| What exactly is the role of a space agency like NASA, created during a Cold War competition that ended two decades ago, in today’s society? |

There have been plenty of examples of this process in recent weeks. Early this month the National Research Council (NRC) released a congressionally mandated report assessing NASA’s strategic direction, offering a number of findings and options. There have also been other reports and discussions about what NASA should be doing, from a Congressional committee to an industry organization to a former astronaut. And the advice-giving cycle begins anew later this week with the first meeting of another NRC committee, this one to specifically examine NASA’s human spaceflight program.

This wave of advice comes at an interesting time for NASA. At first glance, the agency’s future appears to be status quo, given the results of the November elections that kept the Obama Administration in office for the next four years while maintaining the balance of power in Congress. At the same time, though, there is the threat of sequestration, with its across-the-board cuts for NASA and other agencies; even if those automatic cuts are avoided in the next two weeks, the space agency’s budgets for at least the near future are likely to be no larger than its most recent one. There’s also, as some recent events illustrate, a lack of enthusiasm about NASA’s goal of mounting a human mission to a near Earth asteroid by 2025. This raises a key question: what exactly is the role of a space agency like NASA, created during a Cold War competition that ended two decades ago, in today’s society?

No strategy, no enthusiasm

On December 5, the NRC released a report titled “NASA’s Strategic Direction and the Need for a National Consensus.” The report, requested by Congress in the fiscal year 2012 appropriations legislation that funded NASA, was designed to evaluate NASA’s current strategy, as outlined in the agency’s strategic plan and related documents, although it was not asked to determine what NASA’s goals should be. The NRC established a committee to carry out the study, which held several public hearings over several months (see “NASA’s past considers its future”, The Space Review, July 9, 2012.)

The committee’s conclusion was blunt. “The 2011 NASA strategic plan and associated documents do not, in our view, constitute a strategy,” said UCLA professor and chancellor emeritus Albert Carnesale, who served as chairman of the study, in a telecon with reporters the day of the report’s release. The documents list NASA’s goals and programs, he said, “but there are no sense of priorities and no guidance for resource allocation, both of which would be essential to anything that would be called a strategy.”

That lack of strategy, the committee noted in the report, is rooted in a lack of agreement about just what NASA should be doing. “There is no national consensus on strategic goals and objectives for NASA,” the report stated. “Absent such a consensus, NASA cannot reasonably be expected to develop enduring strategic priorities for the purpose of resource allocation and planning.”

A major finding of the report is that NASA’s 2025 asteroid mission goal isn’t widely accepted, even within the agency itself, as the committee found only “isolated pockets of support” for the goal announced by President Obama in April 2010. “If you ask people in the bowels of NASA, in the field offices—and we spoke with everybody from the directors of each of the field offices to college interns and everybody in between—this is not generally accepted,” Carnesale said of the asteroid mission goal. “It hasn’t been explained to them why this is the goal.”

| “What has been happening recently is not reaching a consensus on what the focus should be, but rather, a compromise that includes everything, without adding funding,” Carnesale said. “Hence the notion that NASA has far too much program for its budget.” |

Carnesale said this lack of support doesn’t mean that the agency’s rank-and-file reject the notion of a human asteroid mission, but rather that they see little evidence that NASA is seriously pursuing it: no specific funding line for the mission, no identification of the specific asteroid for the mission, as well as skepticism about whether an asteroid mission really is the most logical next step for human mission beyond Earth orbit. “I do not want to imply that there was uniform belief that the asteroid mission was a bad idea,” he said. “Rather, there was not a consensus that that really is the next step on the way to Mars.”

Another, less surprising finding of the committee was a mismatch between what NASA is asked to do and the budget provided to carry out those missions. Carnesale said that was linked to the lack of a clear consensus on what NASA should do. “What has been happening recently is not reaching a consensus on what the focus should be, but rather, a compromise that includes everything, without adding funding,” he said. “Hence the notion that NASA has far too much program for its budget.”

The report recommended that the administration take the lead on forging a new consensus for NASA’s strategic direction, one that “should be ambitious, yet technically rational, and should focus on the long term.” That, the report stated, will require reaching an understanding with Congress, as well as with any potential international partners who may be involved in future missions. “A presidential statement does not a consensus make,” Carnesale said.

The report also offered four options for reducing the mismatch between programs and budgets, without declaring a preference for any of them. One option is to carry out “an aggressive restructuring program” to reduce infrastructure and personnel costs. A second calls for more partnerships with other US government agencies, other nations, and the private sector. The third option simply called for increasing NASA’s budget, while the fourth option suggested NASA “reduce considerably the size and scope of elements” in its portfolio of programs.

In that last option, the committee left open the option of eliminating one or more of those major programs. Could that mean human spaceflight itself is in jeopardy? “Our committee did not see advantages to terminating human spaceflight,” Carnesale said. “At the same time, they saw no strategic rationale for why the human spaceflight program should be 51 percent of the NASA budget.” (NASA’s space operations and exploration programs actually constitute 45 percent of the agency’s fiscal year 2012 budget.)

Congressional concerns

A week after the release of the NRC report, the full House Science, Space, and Technology Committee held a hearing on the subject of that report. Many members present at the hearing seemed to accept the report’s conclusion that there was no consensus in NASA’s strategic direction, but there was no sign of consensus among the committee members themselves about what the agency should be doing.

After the Columbia accident nearly a decade ago “we emerged with guiding principles and goals that were overwhelmingly endorsed by both Republicans and Democrats in the House and Senate, resulting in the NASA authorization acts of 2005 and 2008,” said Rep. Ralph Hall (R-TX), the outgoing chairman of the committee, in his opening statement. That consensus was broken by the Obama Administration in 2010, he claimed. “The current agreement, if it can be called that, is not a consensus as much as it is a compromise,” he said of the 2010 NASA authorization act. “It’s been clear over the last few budget cycles that there are fundamental disagreements.”

| “Given the expense of the redundancy necessary in a manned program” and the need to maximize the benefits of the agency’s limited budget, Rep. Harris suggested, “isn’t it time to say that maybe manned programs should be really rare and reserved for rare occasions because they just don’t deliver the bang for the buck?” |

The lack of support for a human mission to an asteroid came up during the hearing. “There are many geopolitical, scientific, exploration, commercial, and educational objectives that could be achieved at the Moon,” said Scott Pace of George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute, one of five witnesses at the hearing. He cited interested in the Moon among a number of nations, from Russia and Europe to several Asian nations. “And in contrast, the case for a human mission to an asteroid is unpersuasive and unsupported by technical or international realities. We should be visionary, but focused on practical actions.”

“The national space policy of 2010, I think, is actually a very good document,” Pace said later in the hearing. “The part that, as a policy professional, sticks out for me is the section on civil space exploration, the asteroid and Mars aspect of it, which, to my mind, really comes a bit out of left field.”

Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX), who will take over the chairmanship of the committee in January, asked about the asteroid goal as well. “Is such a mission absolutely necessary to help us get to Mars, or are there alternatives?” he asked former astronaut Ron Sega, who served on the NRC committee. Sega noted that there are several paths for getting humans to Mars, but that neither he nor the committee identified a preferred one. “There were many questions that concerned us as the path forward,” Sega said of the asteroid mission.

Smith also quizzed Pace on public interest in space exploration and what goals the agency should pursue. “Public opinion has actually been remarkably stable for space activity” over the years, Pace said, never as high as some thought during Apollo but not as low as some have argued since. “The American public have a sense, I think, that we’re an exploring nation, we’re a pioneering nation, and they expect, or assume, that our leadership is, in fact, doing that.”

The committee, though, showed no signs of consensus among its own members about what it means to be exploring or pioneering space. Some expressed regret that the administration cancelled the Constellation program in 2010. Former committee chairman Rep. James Sensenbrenner (R-WI) said it was fortunate that Congress mandated the development of the heavy-lift Space Launch System (SLS) rocket; while he supported commercial cargo and crew efforts, he said, “it’s up to NASA to develop the heavy-lift rocket because the private sector doesn’t have enough funds to do it by itself and that heavy-lift rocket needs enough thrust to overcome the administration’s shortsightedness.”

Another former committee chairman appearing as a witness had different feelings about Constellation. “Financially, the Constellation program was in an unsustainable cost profile and it was about to eat alive the science programs and a number of other things inside of NASA,” said Robert Walker. He expressed support for the option in the NRC report calling for more partnerships, in particular with the private sector. That included selling sponsorships and naming rights for NASA missions, which he believed could bring in hundreds of millions of dollars above and beyond standard appropriations. “When the GoDaddy Rover is traversing Martian terrain, we will be more solidly on our way to fulfilling our destiny in the stars,” Walker said.

Rep. Dana Rohrabacher (R-CA) had a very different vision of what NASA should be doing. Given the growing national debt, he warned, “I don’t believe the American people are going to put NASA on the top of their priority list, which means that we have to be even more creative” in coming up with goals and missions for NASA. He suggested the agency should take on bigger roles in space debris cleanup and planetary defense. “I believe that NASA should be the one who is actually pushing the envelope on what space-based assets will benefit humankind in the future.”

Rep. Andy Harris (R-MD) raised the question of whether NASA should have a major human spaceflight program at all. “Given the expense of the redundancy necessary in a manned program” and the need to maximize the benefits of the agency’s limited budget, he suggested, “isn’t it time to say that maybe manned programs should be really rare and reserved for rare occasions because they just don’t deliver the bang for the buck?” That was opposed by some of the witnesses, including Pace, who noted that NASA is more than just a science agency. “Human spaceflight is probably the most interdisciplinary scientific and technical activity that this country can engage in,” he said. “That’s where the benefit is, from pushing into the unknown.”

A pioneering alternative

If NASA’s overall strategy is wrong, or even missing, what should the space agency be doing instead? In a report issued the day before the NRC’s study came out, the Space Foundation proposed a fundamental redirection of NASA, one that would reshape the purpose of the space agency.

“The Space Foundation believes the problems currently facing NASA exist primarily because the United States has never taken the time to figure out, at an existential level, what a space program does, why it does it, what it should do, and how to proceed,” argued the organization in its report, “Pioneering: Sustaining U.S. Leadership in Space.” In short, NASA has no clear, defining purpose.

| “A pioneering paradigm for a space program leads to the idea that the purpose of the space program is to incorporate the rest of the Solar System into the human sphere of influence,” the report states. |

The Space Foundation makes the case in the report for a new fundamental purpose for NASA, which it summarizes in that key word in the report’s title: “pioneering.” The report describes pioneering as being the first to enter a region and developing infrastructure to open it up for others, and divides it into four phases: access, the logistics of getting someplace new; exploration, finding out what is there; utilization, making use of what is there for other purposes; and transition, handing over those activities to others and starting the process over again.

“A pioneering paradigm for a space program leads to the idea that the purpose of the space program is to incorporate the rest of the Solar System into the human sphere of influence,” the report states. “Pioneering is fundamentally an enabling and capacity-building activity.”

The report includes a number of strategic recommendations that flow from adopting that pioneering model for NASA. At the strategic level, the Space Foundation called for revising the Space Act, making pioneering the agency’s primary purpose and eliminating many of the other purposes for NASA in the bill that are no longer relevant. A second recommendation is to streamline NASA, divesting it of roles no longer relevant to pioneering and, in some cases, the personnel and infrastructure associated with those roles. The report also proposed what it considers a more stable leadership structure, with the NASA administrator appointed to a five-year, renewable term, and the creation of a commission that would oversee and approve a long-term (up to 30 years) plan for the agency. A final strategic recommendation offered several options for more stable funding for NASA, including multi-year appropriations and a “revolving fund” to optimize funding profiles for major programs.

The report also included a number of more tactical recommendations to carry out this pioneering approach, from creating specific goals to gauge the success of the International Space Station (ISS) to a “zero-baseline review” of existing NASA regulations to determine which ones are relevant today. Included in that list is perhaps a more strategic one: realigning space within the executive branch, so that there would be one person—not, mot likely, the NASA administrator—responsible for issues like overseeing the space industrial base and coordinating policy among agencies.

“We think there needs to be a chief executive for space within the government,” said Space Foundation CEO Elliot Pulham at a Capitol Hill event on December 4 to roll out the report. “We have not called this a ‘space czar’ or a ‘Secretary of Space’ or any other label, although one I like is ‘Secretary of the Exterior,’” he quipped.

Of all those recommendations, arguably the most controversial one is the suggestion to shed non-essential missions from NASA’s mandate, along with accompanying personnel and facilities. Such a proposal isn’t new: in the past some have made proposals to, for example, transfer NASA’s earth sciences work to NOAA, or its aeronautics activities to FAA, regardless of whether those organizations were interested in or capable of taking over those functions. Moreover, any discussion of closing NASA facilities has traditionally been civil space policy’s third rail, given the strong opposition any move would generate from members of Congress representing the affected centers.

The Space Foundation report was careful not to identify what parts of NASA should be divested to other agencies or the private sector. “We tried to avoid commenting on specific existing programs or specific destinations,” Pulham said when asked about that. “We think that once you’re focused on pioneering, it will become evident” what programs to focus on, and what should be transferred.

Make money and save the planet

Another perspective on what NASA should be doing comes from former astronaut Tom Jones, a planetary scientist who flew on four Space Shuttle missions from 1994 through 2001. He sees a NASA proceeding too slowly towards its current goals, and an agency that should be redirected to roles that could help generate wealth to support more ambitious space exploration plans.

In a presentation last week at the Space Policy and History Forum at the National Air and Space Museum, he offered his assessment of the direction of NASA’s space exploration efforts, including his own concerns about the 2025 goal for a human asteroid mission. “I’m excited about that because I’m a planetary scientist who loves asteroids,” he said, but saw little movement towards that goal. “The Space Launch System and Orion are not maturing rapidly enough to start missions to asteroids in 2025. So, maybe, five years after that we’ll do the first one.”

| Jones offered a one-sentence explanation of his concept: “Make money in space and protect the planet at the same time.” |

Jones is also skeptical that NASA’s long-term human spaceflight goal—missions to Mars—will be carried out in the next three decades. “My own personal view is that, aside from robotic scientific exploration, there is very little to convince me that we’re going to get any greater access to Mars in the decades ahead,” he said. Of human missions there, he argued, “I don’t think it’s affordable, I don’t think anybody in the government is willing to take the risk of sending people out on such a dangerous three-year expedition.”

He proposed a different direction for NASA, one that would reorient the agency to accessing and utilizing, in cooperation with the private sector, resources on the Moon and on near Earth asteroids (NEAs). “I think what we ought to do is to take these next ten years and reorient NASA to early access to space resources, with NASA as the instrument that then demonstrates commercial potential via lunar robotic and near Earth asteroid sampling,” he said.

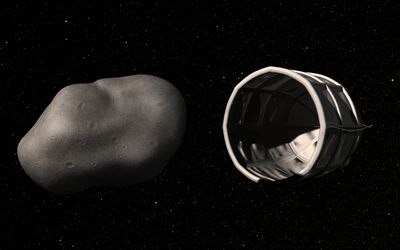

One of the biggest differences between his approach and NASA’s current plans is that, instead of sending humans out to an asteroid, NASA would use robotic spacecraft to send a small NEA back to the vicinity of the Earth. He cited a study by the Keck Institute of Space Studies on the feasibility of an “asteroid retrieval” mission that showed how a robotic mission could capture a 500-ton asteroid (about seven meters in diameter) and move it into high lunar orbit. Once in lunar orbit, astronauts could then easily visit it to both study it and perhaps even work to extract resources, notably water ice and other volatiles, which would have value for other space activities.

“Why would we want to bring a rock back towards our planet?” he asked. “It’s a great destination for humans to use their talents and skills.” Such a mission would have a variety of roles, from offering a stepping-stone for later human exploration missions to testing techniques for planetary defense. “It’s the only way humans are going to get to an asteroid by the mid-2020s.”

That mission would be part of a broader architecture that includes demonstrations of deep space exploration systems and material processing technologies on the ISS, robotic landers and rovers on the Moon (including commercial efforts being developed as part of the Google Lunar X PRIZE competition), and possibly lunar sample return missions, where robotic landers place samples in orbit for return to Earth on crewed Orion missions.

A key element of this approach, he said, would be the commercial exploitation of lunar and asteroid resources. A typical 500-ton asteroid, he noted, would have about 200 tons of water ice and other volatiles. “NASA guarantees that they’ll purchase tons of propellant from a provider from this object or others that are recovered,” he said. “You get commercial delivery of that water to lower the cost of deep space operations for people and robots.” That would eventually lead, he said, “to an economic expansion into cislunar space, where raw materials and solar energy are available, people are involved, commercial companies are involved, getting their own material by duplicating that initial demo that NASA did.”

Asked to summarize his concept in an elevator pitch, Jones offered a one-sentence explanation: “Make money in space and protect the planet at the same time.”

Would such an approach, though, put NASA in competition with private ventures like Planetary Resources, which seek to also access NEA resources but without the support of the space agency? Jones, who also serves on Planetary Resources’ board of advisors, suggested that the stakes were higher for NASA than for any private venture. “I applaud that kind of innovation and spirit,” Jones said of private efforts. “The danger to them is that they lose their shirts” if they fail. “NASA risks becoming irrelevant if they don’t get into this realm.”

What next?

All of these reports, presentations, and hearings point to one thing: a general sense of unease about NASA’s current direction, including a lack of enthusiasm about the goal of sending humans to an asteroid by the middle of the next decade. At the same time, though, there is no fundamental agreement on what NASA should be doing instead, just lots of ideas for missions architectures, policies, and general philosophies for running NASA.

To some, that might suggest a “rudderless” NASA, but the reality may be just the opposite: too many people trying to win support for their particular programs, fighting over budgets that will remain flat, at best, for the near future. “I don’t it’s rudderless,” the Space Foundation’s Pulham said of NASA. “I think the problem is that we’ve got 18 or 20 rudders, and they’re all trying to steer the ship in a different direction.”

| “I don’t it’s rudderless,” Pulham said of NASA. “I think the problem is that we’ve got 18 or 20 rudders, and they’re all trying to steer the ship in a different direction.” |

NASA has had a sharp, well-defined focus in the past, most notably early in its history, when President Kennedy, with the support of Congress, charged the agency to send humans to the Moon by the end of the 1960s. “Unfortunately, basing that purpose on a concrete destination meant that NASA’s focus lasted only until the destination was reached,” the Space Foundation noted in its “Pioneering” report. “The challenge today is properly articulating the purpose of NASA in such a way that progress can be sustained in the long term rather than disappearing the way it did at the end of the Apollo program.”

That aligns with the recommendation of the NRC report, which said the administration “should take the lead in forging a new consensus on NASA’s future that is stated in terms of a set of clearly defined strategic goals and objectives.” The report didn’t attempt to articulate what those goals and objectives should be, only underlining their importance in developing a strategy that would allow NASA to make better informed decisions about programs and budgets.

The question, though, is whether there is any appetite to tackle such a fundamental examination of NASA’s purpose. Space typically has a low priority in the larger national policy scene, and the administration would likely argue that it’s done its part to reorient NASA with its 2010 national space policy and related directives. Barring a calamity of some kind, there may be little incentive by the administration to revisit those policies in its remaining four years in office.

That would also impair any effort to try and reorganize NASA and improve its efficiency. Carnesale, chairman of the NRC committee, said there’s a widespread belief that NASA has too much infrastructure in the form of its ten field centers, but any major changes, such as closing one or more centers, would be politically difficult. The committee asked former NASA administrators if the current center structure made sense, and most, he said, “decided relatively early in their tenure that it would take all of the political capital they had, and then some, to deal with that question, so they decided it was better to spend their time on something else.”

In that sense, then, the threat of the “fiscal cliff” and sharp spending cuts may be a perverse blessing for NASA. A significant budget cut, either of the automatic variety triggered by sequestration, or a more tailored one developed as a solution to avoid those automatic cuts, would provide NASA and policymakers on both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue with a renewed incentive to examine how to most effectively make use of those reduced dollars. On the other hand, it could also just lead to more squabbling and compromise decisions to stretch out programs, which do little to address the more fundamental questions, or even save money over the long term, for that matter.

In the meantime, the advisory process continues, with the first meeting this week of the NRC’s human spaceflight panel, as commissioned by Congress in the 2010 NASA authorization bill. It will, among other things, provide “findings, rationale, prioritized recommendations, and decision rules that could enable and guide future planning for U.S. human space exploration.” However, the committee’s final report isn’t scheduled for release until May 2014, likely too late to stimulate much change from the current administration. In that case, it will be in good company, alongside the many other reports published over the years that offered proposals for changing NASA but failed to substantially change the nation’s civil space program.