Visiting the shuttlesby Jeff Foust

|

The space shuttle Discovery at the Udvar-Hazy Center outside Washington, DC. (credit: J. Foust) |

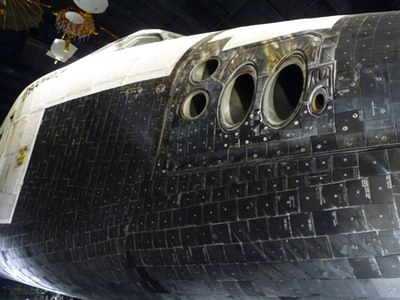

A closer inspection, though, reveals a key difference. Enterprise, which never flew in space, had the pristine appearance of a showroom model. Discovery, which spent a year in space over its 39 missions, has the weathered look of the real thing. The black tiles on the nose and underside are scuffed and streaked from dozens of reentries, while the white thermal blankets are discolored in many locations.

The shuttle is clearly the centerpiece of the hangar, and those in the hangar during a recent visit clearly had their attention focused on it, versus the other artifacts along the sides. Beyond that, though, Discovery doesn’t get much more special attention in the museum; after all, it’s just one of a number of historic vehicles there, just around the corner from a Concorde, Boeing’s Dash 80 jetliner prototype, and the Enola Gay.

A closeup of Discovery reveals the wear and tear from over three dozen missions. (credit: J. Foust) |

Across the country, the California Science Center, located in Exposition Park south of downtown LA, opened its Samuel Oschin Space Shuttle Endeavour Display Pavilion at the end of October, a couple of weeks after the orbiter completed a weekend-long journey through city streets from Los Angeles International Airport to the museum. This simple hangar will be the shuttle’s home for at least the next few years until the museum builds a permanent facility.

Like the Udvar-Hazy Center, admission to the California Science Center is free, although both charge for parking ($10 at the California Science Center and $15 at the Udvar-Hazy Center, although the latter waives parking fees if you arrive after 4 pm.) However, tickets are required to see Endeavour, presumably to limit crowding. The museum recommends getting these timed-entry tickets in advance through its website; the tickets are free save for a $2 service charge. Checking the night before a weekday visit last week, there were no tickets available for entry after 12:45 pm although, when visiting the museum itself, there were no signs of crowds or long lines to see the shuttle.

To see Endeavour itself, you go through a special exhibit about the shuttle, with a hodgepodge of artifacts: tires from Endeavour’s final mission, STS-134; a shuttle toilet; and consoles and displays from a control room Rocketdyne operated in nearby Canoga Park, California, to monitor the performance of the shuttle’s main engines during launch. The exhibit also features a short film showing, in time lapse, the transport of the shuttle from LAX to the museum.

Endeavour is mounted a few meters above the ground, high enough for people to be able to walk underneath it. (credit: J. Foust) |

Then it’s on to the shuttle itself. Endeavour’s display in the museum is, at first glance, similar to Discovery’s at the Udvar-Hazy Center. One difference is that, while Discovery is resting on its landing gear, Endeavour is instead attached to columns that hoist the orbiter a few meters above the floor, high enough to allow people to walk underneath it, something not possible with Discovery. The columns also serve as seismic isolators to protect the shuttle in the event of an earthquake.

Endeavour’s hangar is smaller than the one housing Discovery, but it’s also less cluttered: there are only a few other artifacts sharing space with Endeavour, including a SPACEHAB module and a Space Shuttle Main Engine. Placards listing all 135 shuttle missions line the walls (with Endeavour’s 25 missions highlighted), and in front of Endeavor’s nose there’s a small gift shop.

Endeavour’s current home is not intended to be its final home: the museum is raising funds to build a permanent facility, called the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center, that will display the orbiter in a very different way. The shuttle will be erected vertically as if on the launch pad, with a series of viewing platforms where the gantry would be. This will be a unique way to display the orbiter, but perhaps less intimate: you won’t be able to get as close to it as you can now when you can around and underneath it, its weathered surfaces just beyond reach.

Above: a view of the crew cabin of Endeavour from March 1990, when the orbit was still being assembled. Below: a view of the forward section of Endeavour as it appears today. (credit: J. Foust) |

This preference for the Endeavour’s current configuration might be a unique personal one, though. Seeing Endeavour in this current configuration brought back for me memories of seeing Endeavour for the very first time, when, as a college student in 1990, I toured the Rockwell plant where Endeavour was assembled in Palmdale, California. Walking around and underneath Endeavour at the museum brought back memories of doing the same in Palmdale, more than two years before its maiden flight. For me, it closed a circle, seeing the same spacecraft before its first mission and after its last.

By this summer the other two shuttle orbiters will be back on display. Enterprise was on display for a few months last year on the deck of the Intrepid in New York City, but Hurricane Sandy wrecked that temporary home in late October. Last week the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum said it had started work on a new display pavilion for the orbiter that would open in the spring. The Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex is constructing a building for Atlantis that will open in July, displaying the orbiter at an angle, as if it was flying through space. Until then, the California Science Center and the Udvar-Hazy Center offer fine opportunities to see these historic retired spacecraft up close.