Higher Look: A top secret reconnaissance mission in 1982by Dwayne Day

|

| The NRO explored the possibility of modifying the GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite to operate at a much higher operational altitude, thereby increasing its ability to see more territory. This new capability was referred to either as “Highboy” or “Higherboy.” |

But the United States intelligence community was also facing a dilemma: a gap had opened in its intelligence collection capabilities. The United States deployed three kinds of photo-reconnaissance satellites. Two had high-resolution capabilities and the third was able to image broad areas of territory in a single pass over the Soviet Union, enabling photo-interpreters to count the number of strategic bombers deployed at most Soviet airfields and to spot mobile ballistic missiles in the field. But intelligence officials realized that they would have no broad-area coverage for nearly a year, and they sought a stopgap measure to close that gap. The solution was to launch a specially modified version of the GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite.

The GAMBIT was the most powerful reconnaissance satellite ever produced by the National Reconnaissance Office. Although later satellites had larger image-resolving mirrors, they flew in higher orbits and so their resolution of objects on the ground was not as good. GAMBIT’s large mirror, high-resolution film, and its ability to fly as low as 72 nautical miles (133 kilometers) above the ground, allowed it to take very high resolution photos. The United States launched 92 GAMBIT high-resolution reconnaissance missions between 1963 and 1984. The GAMBIT-1 series entered service in 1963 and was retired by 1967, superseded in 1966 by the GAMBIT-3 series with a more powerful camera. The last of 54 GAMBIT-3 missions was launched in April 1984.

Over its 21 years of operational service, GAMBIT-3 underwent numerous upgrades, gaining additional capabilities and ever-higher resolution. The upgrades included:

1967: Ultra thin base film

1968: Use of SO-121 color film

1969: Dual Satellite Recovery Vehicles (SRVs), 14-day orbital life

1970: Use of 1414 High definition black and white film

1970: Low coefficient optical materials

1970: Factory to pad operations

1971: 20-day orbital life

1971: Lens formula change R-5

1972: 30-day orbital life

1972: Exposure slit change

1973: Increased film capacity (10,800 feet)

1973: Improved optical quality

1973: Satellite-to-satellite (SSquared) imaging capability

1973: Use of SO-124 high-definition black and white film

1973: Use of SO-131 false color IR film

1974: 45-day orbital life

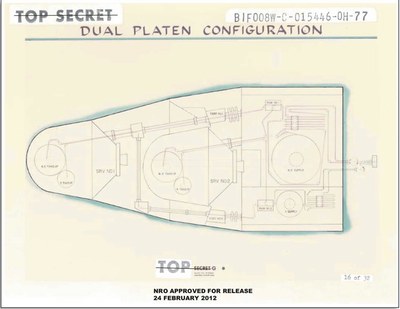

1977: 9x5-inch dual platen camera

1977: 75-day orbital life

1982: Dual mode capability demonstrated

The last significant development in the GAMBIT program came as the program was nearly over, but it was not a new development.

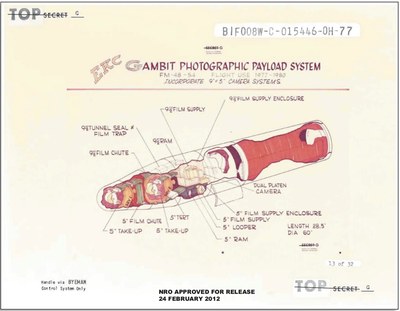

The photographic system for the dual mode GAMBIT. |

In the early 1970s, as the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) planned to retire the CORONA search satellite and replace it with the HEXAGON, NRO officials became concerned that HEXAGON schedule slips would leave the United States without broad area search coverage for a substantial period of time. So they explored the possibility of modifying the GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite to operate at a much higher operational altitude, thereby increasing its ability to see more territory. This new capability was referred to either as “Highboy” or “Higherboy.” These were nicknames, not formal codewords, and had the disadvantage of providing a clue about the satellite operating mode. Eventually, those involved in the program settled on the ambiguous designation “dual mode.”

| By 1981 the NRO was facing a dilemma. The next HEXAGON spacecraft would not be ready to launch until spring 1982, creating a gap of over a year. This made imagery intelligence analysts worried. |

The technical modifications for dual mode operations included modifications to the camera system to adjust it for the higher orbit. For example, at higher altitude, the image of the Earth below would move through the camera more slowly. The camera had to account for this moving image in order to prevent image smear on the film, and therefore dual mode modifications included tweaking the camera to provide the slower image motion compensation required. Another modification probably involved one of the GAMBIT’s two Satellite Recovery Vehicles to enable it to descend from a higher altitude than normal. Originally, dual mode operations involved 80 days operation at 500 nautical miles (926 kilometers) altitude and 40 days at 75 nautical miles (139 kilometers).

In 1971 the NRO ordered three Higherboy modification kits for delivery by 1972. HEXAGON eventually launched in June 1971, and the dual mode GAMBIT-3 was unnecessary. The dual mode equipment was then placed in storage, but reconnaissance officials were aware of its availability.

By 1981 the NRO was facing a dilemma. HEXAGON Mission 1216 was launched on June 18, 1980, returning its fourth and last film return vehicle to Earth in March 1981. But for reasons that remain unclear, the next HEXAGON spacecraft would not be ready to launch until spring 1982, creating a gap of over a year. This made imagery intelligence analysts worried. The Committee on Imagery Requirements and Exploitation, known by its acronym COMIREX, was responsible for selecting targets for intelligence satellites. COMIREX officials were concerned that there would be no broad area search imagery for twelve to fifteen months at a time when the new president’s defense policies depended upon a good accounting of Soviet strategic actions.

During this time the NRO had other assets in orbit, the third and soon fourth KH-11 KENNEN electro-optical imagery satellites. The KENNEN, unlike GAMBIT and HEXAGON, beamed its images to Earth via a relay satellite. But KENNEN’s images were not as high-resolution as GAMBIT, and did not cover as much area as HEXAGON.

The members of COMIREX determined that it was important to gain broad area coverage of various spots, including the Soviet Union, and in October 1981 COMIREX, following a presentation from the NRO about the dual mode mission, recommended that such a mission be flown to close the gap. The decision was not unanimous, however, and the Navy representative to COMIREX objected, advocating a standard high-resolution GAMBIT-3 mission. His specific reasons are not known, but the Soviet Union was expanding its navy and had a number of large surface combatants and nuclear powered missile submarines under construction, and high-resolution imagery was valuable in determining their construction and capabilities.

The photographic system for the dual mode GAMBIT. |

In addition to the GAMBIT-3’s standard camera with its nine-inch wide film, the camera incorporated a device that allowed the image to be redirected onto a second platen holding five-inch film. This enabled the GAMBIT-3 to perform its standard mission with the main camera, and to carry special film, such as infrared or experimental film, in the second camera. Both rolls of film then went to the two Satellite Recovery Vehicles at the front of the spacecraft.

| On March 20, 1982, the first SRV was ordered to disconnect from the spacecraft and reenter. But an “electro-explosive device” on an in-flight disconnect unit did not operate. |

GAMBIT Mission 4352 was launched on January 21, 1982, aboard a Titan IIIB Agena at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. The goal was a 120-day reconnaissance mission to capture both search and high-resolution photography. The plan was to fly the first 90 days of the mission at 300–350 nautical miles (556–648 kilometers)—significantly below the original 500-nautical-mile design altitude—and the last 30 days at 78 nautical miles (144 kilometers). But because the weather was excellent over several targets over China, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, parts of Africa, and one other still-classified area, the high-mode was extended to 97 days and the low-mode was shortened to 23 days. Film from the first 500 revolutions was stored in the first SRV, and film from the last 625 revolutions was stored in the second SRV. The second SRV had imagery from 125 high-altitude revolutions and 248 low-altitude revolutions.

But something went wrong.

On March 20, 1982, the first SRV was ordered to disconnect from the spacecraft and reenter. But an “electro-explosive device” on an in-flight disconnect unit did not operate. The device that malfunctioned was new and had not been flown before, and had not been ground tested under conditions simulating the high-altitude dual mode mission. The SRV did not cleanly separate from the spacecraft. Backups to ensure destruction of the reentry vehicle and its payload did not operate correctly because of the original failure.

Fortunately, the internal “bucket” that contained the film was separated from the heat shield and the thrust cone that deorbited the vehicle. Designers had developed this technique in event an SRV was stranded in orbit, figuring that the film would slowly degrade in space, and when it eventually fell to Earth the bucket and its film payload, lacking a protective heat shield, would burn up.

On the ground, controllers quickly determined that the SRV could not be successfully recovered. So they decided to focus instead on the rest of the mission, collecting remaining area search imagery and the low-altitude mode imagery, and recovering the second SRV.

Ground controllers determined that the first SRV could spend up to 30 years in orbit before falling back to Earth. But they were concerned that the fate that befell the first SRV could also happen to the second one. So they devised a procedure to prevent that from happening. They commanded the entire vehicle to de-orbit boost and then separated the second SRV. This proved fortunate, because the second SRV’s in-flight disconnect also malfunctioned. However, the SRV still separated due to the new procedure and it was successfully air recovered on May 23, 1982.

Unfortunately, the film on the second SRV was degraded. Despite months of investigation by many different experts inside and outside the program, nobody could determine the source of the degradation.

HEXAGON Mission 1217 was launched on May 11, 1982, and restored broad area imagery coverage. The GAMBIT program was nearing its end. GAMBIT-3 Mission 4353 launched on April 15, 1983, and operated successfully for 129 days, making it the longest GAMBIT mission ever flown. GAMBIT-3 Mission 4354 launched on April 17, 1984, ending the highly successful GAMBIT program.

| On September 28, 2002, the bucket came down, landing in deep ocean waters and presumably sinking immediately. No recovery operation was conducted. The last Higherboy mission, conceived in the early 1970s, was finally over. |

Mission 4352’s unusual orbit did not go unnoticed by satellite spotters. Anthony Kenden, who regularly wrote about American military space efforts and monitored the orbits of American satellites by obtaining two-line element data directly from NORAD—before the United States government stopped releasing such data—noticed that the satellite was unlike previous Titan IIIB Agena’s launched from Vandenberg. He speculated that it was a radar satellite. Later, famed reporter Bob Woodward wrote that the United States had launched a radar satellite in 1982 designated INDIGO. However, Woodward may have been referring to an ongoing radar satellite program with that designation, and simply confused it with a specific launch.

In the summer of 2002 the NRO Flight Safety Working Group learned that the mission 4352 bucket, containing more than 6,800 feet (2,070 meters) of photoreconnaissance film, was soon going to reenter the Earth’s atmosphere. By this time, the film was undoubtedly substantially degraded, and reentry would damage it further or even destroy it. But it was possible that something from this still-classified mission could fall to the ground in unfriendly territory.

The NRO requested that Air Force Space Command concentrate its sensors on the several pieces of debris from the mission that were still in orbit, determining which one was the wayward bucket. Space Command used radar and other sensors to track the bucket and determined that it would reenter the atmosphere in four to five weeks.

The National Reconnaissance Operations Center started monitoring the payload closely. They could not determine a reentry point until only approximately four hours before reentry. As reentry grew near, they determined that it would come down in the South Atlantic near Antarctica. Radars tracked the bucket and the Aerospace Fusion Center used data from Defense Support Program (DSP) satellites that detected the heat of the bucket’s fiery reentry. On September 28, 2002, at 0218 UTC (10:18 pm on the 27th at NRO Headquarters outside Washington, DC), the bucket came down, landing in deep ocean waters and presumably sinking immediately. No recovery operation was conducted. The last Higherboy mission, conceived in the early 1970s, was finally over.