Redirecting an asteroid missionby Jeff Foust

|

| “This is truly a science that is in its renaissance,” Garver said of efforts to discover and study asteroids. |

That proposed mission—called at the time the Asteroid Retrieval Mission, or ARM—raised more than a few eyebrows when NASA announced it in April. Some questioned the technical feasibility of the concept (which is based on a 2012 study by the Keck Institute for Space Studies at Caltech) while others wondered how useful it would be for science or human exploration. Now, with some members of Congress making moves to block the effort, NASA is showing signs of subtly shifting the focus of the proposed mission, and the overall initiative, more towards the less controversial role planetary defense.

An asteroid Grand Challenge

On June 18, NASA held a half-day “industry and partner day” about its asteroid initiative, with an audience of industry officials and other interested people filling the auditorium at NASA Headquarters in Washington. The expectation from the meeting was that NASA would provide more information about its plans for the initiative, particularly the ARM, and the role the private sector and others could play in supporting it.

However, NASA offered a somewhat different emphasis at the meeting. NASA used the event to unveil a “Grand Challenge” related to near Earth asteroids and planetary defense. The language of the challenge, at least, is simple enough: “Find all asteroid threats to human populations and know what to do about them.”

The Grand Challenge is linked to a White House initiative of the same name, which the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) defines as “ambitious goals on a national or global scale that capture the imagination and demand advances in innovation and breakthroughs in science and technology.” Other such challenges announced by various agencies include one to make solar power cost-competitive with coal power, and one to increase access to health care for pregnant women and newborns by 50 percent.

“If you look at new knowledge and scientific discovery, asteroids are one of those unique, really current activities” enabled by technological advances, NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver said at the forum. “This is truly a science that is in its renaissance.”

“This effort is also important because it demonstrates a willingness to tackle a problem that is long term in nature,” said Tom Kalil, deputy director for technology and innovation at OSTP. (Officials emphasized this new challenge was not driven by any particular threat posed by a near Earth object, or NEO.) “In a society that is often dominated by the 24-hour news cycle or the quarterly earnings report or getting ready for the next election or responding the next tweet, it’s very important that we have an increased capacity to work on long-term problems.”

What exactly will be involved in this new Grand Challenge wasn’t immediately clear from the forum, other than a willingness by NASA to consider new and non-traditional partnerships to support the search for and analysis of NEOs. Jason Kessler, program executive for the Grand Challenge in NASA’s Office of the Chief Technologist, suggested roles for new partners in the analysis of lightcurves (the changes in brightness of asteroids as a function of time as they rotate), development of shape models of asteroids from such observations, and even development of new space-based observational capabilities.

“Are there ways that we can creatively bring people in to help with this problem?” Kessler asked, citing examples of “citizen science” in other fields, like GalaxyZoo, where people help catalog galaxies, as ways to get more people involved in the analysis of NEO data. His charts showed an interest in involving a wide range of audiences, from the conventional scientific community to amateur astronomers, entrepreneurs, and technological hobbyists known as “makers,” in this effort.

| “Are there ways that we can creatively bring people in to help with this problem?” Kessler asked of the issue of analyzing observations of NEOs. |

To that end, NASA announced at the forum that it was releasing a request for information (RFI) to solicit ideas for the Grand Challenge and the broader asteroid initiative. The RFI, whose deadline is July 18, is open to just about anyone, with topics ranging from asteroid searches to technologies needed for future missions. “We expect to hopefully get some good ideas and guidance back on effective ways to move forward,” Kessler said, adding that NASA was also planning to hold “digital brainstorming” sessions later this summer and a workshop in the fall to help develop an implementation plan.

The RFI also solicits ideas for carrying out the asteroid mission itself, including technologies needed to capture and move an asteroid as well as for a human mission to it. NASA officials at the forum didn’t offer many new details about the mission concept in these early phases. NASA associate administrator Robert Lightfoot said an internal mission formulation review is planned for the end of July, followed by a more detailed mission concept review around the first of the year.

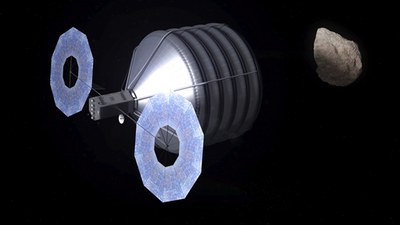

There were signs last week, though, of a shift of the asteroid mission concept more towards planetary defense. NASA has subtly changed the acronym ARM from the Asteroid Retrieval Mission to the Asteroid Redirect Mission. NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations Bill Gerstenmaier said the use of “redirect” in the mission concept is deliberate, since they’re interested in objects that already would pass close to the Earth. “We take advantage of the fact that it’s already coming back so we don’t have to change the velocity in that direction,” he said. “All we need to do is essentially redirect it” into a lunar orbit, taking advantage of the Moon’s gravity. Left unstated was that redirection would also be useful if an object is passing too close to the Earth.

Gerstenmaier also revealed that NASA was looking at alternatives to the initial concept of retrieving (or redirecting, if you prefer) a NEO 7–10 meters across. In one alternative, he said, the robotic spacecraft would go to a larger asteroid, 100 meters across or larger, and “push” on it to change its velocity by millimeters per second. “That small velocity, applied early enough, could be the velocity that deflects this object away from the Earth,” he said, demonstrating this concept for planetary defense. The spacecraft could then capture a small boulder, 1 to 10 meters across, off the surface of the asteroid and move it back to cislunar space.

Congressional opposition to the asteroid initiative

The NASA briefing took place a day before the space subcommittee of the House Science Committee held a hearing on a “discussion draft” of a proposed NASA authorization bill yet to be formally introduced. That draft, though, indicated that at least some in Congress remain unconvinced of the initiative’s merit.

“Consistent with the policy stated in section 201(b), the Administrator shall not fund the development of an asteroid retrieval mission to send a robotic spacecraft to a near-Earth asteroid for rendezvous, retrieval, and redirection of that asteroid to lunar orbit for exploration by astronauts,” a provision of the draft bill states. The section cited in that excerpt states that “the development of capabilities and technologies necessary for human missions to lunar orbit, the surface of the Moon, the surface of Mars, and beyond shall be the goals of the Administration’s human space flight program.”

“While the committee support the administration’s efforts to study near Earth objects, this proposal lacks in details, a justification, or support from NASA’s own advisory bodies,” Rep. Steven Palazzo (R-MS), chairman of the space subcommittee, in his statement opening the hearing. “Because the mission appears to be a costly and complex distraction, this bill prohibits NASA from doing any work on the project, and we will work with appropriators to ensure the agency complies with the directive.”

The hearing’s two witnesses also showed little support for the mission. “I have a great worry about what I believe to be a declining trajectory for NASA and the civil space program,” said former Lockheed Martin executive Tom Young, blaming it on “diffuse” leadership that lacks technical expertise. “As an example of what results from diffuse leadership, with too much authority in the wrong places, is the proposed asteroid retrieval mission. This is a mission that is not worthy of a world-class space program.”

“Personally, I agree with the draft authorization act’s position on the asteroid retrieval mission and I disagree with its position on a sustained lunar presence,” said Cornell University planetary scientist Steve Squyres, who is also chairman of the NASA Advisory Council, referring to another provision in the bill that mandates a program for “a sustained human presence on the Moon and the surface of Mars.” He disagreed, though, with the bill’s approach. “I believe that it would be unwise for Congress to either prescribe or proscribe any key milestones in NASA’s Mars exploration roadmap at this time,” he argued, suggesting that NASA, with oversight from Congress and advisory bodies, is better suited to determine what those milestones should be.

| “This is a mission that is not worthy of a world-class space program,” said Young. |

“I personally don’t see a strong connection between the proposed asteroid retrieval mission and sending humans to Mars,” Squyres said later in the hearing, when asked by a subcommittee member to explain his skepticism about the mission. “But, I believe that NASA should at least be given the opportunity to try and make that case. I haven’t heard it yet.”

The language in the draft bill may not be relevant for a couple of reasons, though. First, strictly speaking, there is no asteroid retrieval mission in the proposed 2014 budget. Rather than a single line item, the $105 million for the asteroid initiative is spread out across three mission directorates within NASA, focused on specific programs and technologies—increased funding for NEO searches and development of solar electric propulsion technology, for example—that can apply to an asteroid mission but also other science and exploration applications.

Second, Wednesday’s hearing made clear there was opposition to the draft NASA authorization bill for reasons beyond the asteroid mission language. At the hearing, key Democratic members spoke out against the bill’s overall authorized spending level for NASA—$16.865 billion for 2014 and the same for 2015—as well as proposed steep cuts in Earth sciences programs.

“This is not a bill ready for markup. This is a flawed draft, starting from its funding assumptions, and I cannot support it in its present form,” said Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX), ranking member of the full House Science Committee. “I also predict that, if passed by the committee, this bill would be DOA in the Senate.”

Even one Republican subcommittee member, Rep. Mo Brooks of Alabama, spoke out at the hearing about language that he felt underfunded the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket, authorizing $1.45 billion for the program when he felt it needed at least $1.8 billion. “Unless I receive differing expertise that satisfies me that our words in support of human spaceflight match our actions and deeds,” he said, “I will have no choice but to vote against and otherwise oppose this authorization act.”

As Johnson predicted, a key senator also expressed concerns about the proposed House bill. “I’m not going to approve of keeping it at 16.8 [billion dollars], because it would run the space program and NASA into a ditch,” said Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL), chairman of the space subcommittee of the Senate Commerce Committee, at a Space Transportation Association luncheon Wednesday, referring to the overall authorized funding for NASA in the House bill.

| Garver admitted there was “a lack of the recognition yet of the importance and value of this mission” among members of Congress. |

Nelson said the Senate would come up with its own draft of an authorization bill no later than mid July, one that would support what he called a “balanced program” of government and commercial human spaceflight as well as science. He did not speak out specifically about the asteroid initiative, but has previously expressed support for the program, making it unlikely language blocking it would make it into the Senate version.

NASA deputy administrator Garver, at Tuesday’s forum, stated several times that the concept had “bipartisan support,” but acknowledged that the agency had work to do to sell it to skeptical members of Congress. Asked about the language in the draft bill, she said there was “a lack of the recognition yet of the importance and value of this mission” among members. “We obviously have not completed our work” in defining the mission and aligning it to key goals, like planetary defense, she said. “I think we really truly are going to be able to show the value of the mission.”

The $105-million question, though, is, as NASA’s thinking about the asteroid initiative evolves, and ideas requested by its RFI pour in, exactly what value does the overall program, and the proposed redirection mission, offer to NASA and the nation in terms of science, technology development, and human exploration?