Mist around the CZ-3B disaster (part 1)by Chen Lan

|

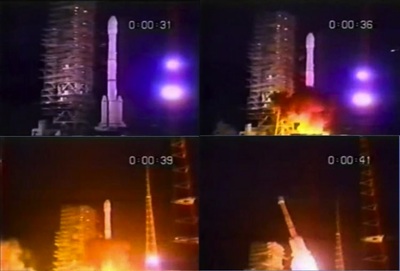

CZ-3B’s final flight and huge explosion. This video was supposed to be taken from the roof of the Mission Command and Control Centre. (credit: CCTV) |

Official accounts

On the same day (February 15), China’s official Xinhua News Agency published a newsflash. Here is the full text:

At 3:01 today, our country’s newly developed Long March 3B carrier rocket failed to launch the Intelsat 708 communication satellite in Xichang Satellite Launch Centre. It was the maiden flight of this launch vehicle. The parties concerned are investigating this accident.

About two weeks later, on March 2, there were more details from another Xinhua report:

According to analysis and interpretation of telemetry data, it is considered that the accident was caused by changes of inertial baseline after lift-off. The particular cause is to be further analyzed and verified… At 3:01 on 15 February, our country’s newly developed Long March 3B carrier rocket lifted off. Anomaly in flight attitude appeared about two seconds later. The rocket pitched down and went right off the flight path. About 22 seconds later, the rocket crashed with nose down and exploded violently. Both the rocket and the satellite were lost. There were no large debris on the site… Up to today, 49 of 57 wounded have been cured and discharged from hospital and 8 are still in hospital. Arrangement has been made for the 6 dead. Checkout and testing shows that launch and testing capability of the Xichang Satellite Launch Centre was not affected… It is able to resume normal operation at beginning of March. More than 80 local houses nearby the launch centre were damaged. The launch centre and the local government provided temporary housing and relief fund to the victims… Except for short time pollution at the explosion site and in air, water source, plant and food were not polluted… China Great Wall has informed all customers and the international insurance industry progress of the investigation. On 28 February, Intelsat was invited to participate in the investigation.

It has to be noted that early reports did not give the location of the impact site. In recent years, many Chinese official news sources have indicated that it was 1,850 meters away from the launch pad. One of the earliest such claims was in the China Aerospace magazine published in April 2000.

| However, for many people in the West, the extent of the accident’s casualties is still the largest unanswered question. |

Though there was no official information about the casualties and damage since then, investigation progress was reported. By the end of February, the fault was localised on the inertial platform. One month later, four possible failure modes were determined. Then, three of the four modes were ruled out, one by one, after careful test and analysis. In mid-May, closed-loop semi-hardware simulation concluded that a circuit fault of the follow-up frame was the most possible cause of the failure. Further analysis and tests, as well as inspection on various components, between June 17 and July 6 led to the final conclusion that the root cause of the launch failure was a poor gold-aluminium bonding point inside the power output module of the follow-up frame’s servo-loop, preventing output of current from the loop and finally causing failure of the inertial platform.

Urged by international insurance companies, China established an independent review committee to assess the results of the failure investigation, as the premise for the former to insure the follow-up Apstar-1A launch. The committee consisted of six experts from the United States, Germany, and Britain. According to Chinese records, it was founded on April 15 and terminated on May13. Only two meetings, one on April 22–23 in the United States and the other on April 30–May 1 in Beijing, took place.

Two years after the accident, the Cox Report was published in the United States, accusing China of acquiring sensitive technologies through the launch failure investigation. It resulted in a more strict space technology export control policy on the US side, and China’s withdrawing from the commercial launch market. The CZ-3B accident changed not only the commercial launch market but also the course of the Chinese space program.

However, for many people in the West, the extent of the accident’s casualties is still the largest unanswered question. Because of the historical lack of transparency of the Chinese space program and lack of information about this accident, they never trust the Chinese official accounts. Someone even described the CZ-3B accident as the worst space disaster in history, overshadowing the Nedelin tragedy in 1960 in the Soviet Union. Seventeen years later, there is still a mist around the accident. In fact, more details have been revealed in recent years. Though not all questions are answered, we are now able to reconstruct the event in most aspects and are able to draw some conclusions. The mist is drifting away slowly.

Screenshots from the video taken by the alleged Israeli engineer. The top two frames show the small park. We can see a damaged rocket fairing mock-up in the left one, and the monument of the ancient rocket, but only the base, in the right one. The hotel was in the background of the scene in these two frames. The bottom two frames show the Coordination Building and the flattened village houses. |

Western witness

Western suspicions emerged on March 23, 1996, when Israel's Channel Two television broadcast what it said was smuggled video footage from Xichang. The video, said to have been made on the day after the launch, shows flattened houses and apartment buildings without walls and roofs, along the road to the launch center. The video was obviously taken from a moving vehicle. The number of damaged houses and buildings in the video shows how large the scale of the disaster was. Many people then believed that much more than six people were killed in the accident, and the Chinese government was trying to cover up the truth, as they always believe. There were different figures of speculated casualties in the Western media, from a few dozens to 300, and even 500. Chinese official media denied the large casualty figure and involvement of any Israeli citizens in the launch. The name of the Israeli who took the video has never been revealed. Today, the video can be easily found on YouTube. It has to be noted that there are at least two video clips, one of which was obviously broadcast on the Japanese Edition of Discovery Channel. The two clips were taken from vehicles going in opposite directions: one was leaving the centre and the other was entering the centre. Were they taken by one person? Where they originated from is still a mystery.

It was not until the last year that the first detailed witness report from the West appeared in the media. Anatoly Zak published an article about the accident in the February 2013 issue of Air & Space magazine. He interviewed a former safety specialist who worked for the satellite builder Space Systems Loral in Xichang to support the Intelsat 708 launch. Zak also accessed the diary of an unnamed US engineer who participated in the launch.

Screenshots of another video clip taken by the alleged Israeli engineer. It shows interior damage, the Coordination Building and village houses. |

During the launch night, the two American engineers were in the Satellite Processing Building, about 2.5 kilometers away from the launch pad. According to the diary, everything went well during countdown. The Chinese inserted a 9-minute hold at T-2:51 minutes and another 45 seconds at T-1 minute, without a reason stated. When the rocket lifted-off, Bruce Campbell, the American safety engineer, was on the roof of the building watching the launch. While the engineer who wrote the diary ran outdoors just after the lift-off. Both of them witnessed the abrupt veering off and immediately realised something unusual happened. The diary described the explosion 22 seconds later in the following terms: “A tremendous light turned 3 a.m. into noon… I heard the biggest explosion of my life, I turned and started to run… I left the ground, I was on the ground, scrambling, wondering why I was down there… I heard glass breaking and shit was flying everywhere.” Campbell and others on the roof descended and scrambled into the building. When a violent shock wave hit the building, a large glass-enclosed entrance shattered into thousands of fragments. They entered the fuelling facility of the building and shut down all air-cons to prevent any toxic gas influx. They remained, or were stranded there until the following morning.

| It was more than seven years after the accident when the first witness report appeared in the Chinese media. |

In the morning, worried that the Chinese were delaying their departure to clean up the crash site, Campbell and one of his colleagues rushed down by bicycle to their hotel near the impact epicenter. “As they approached their hotel, the scale of devastation became fully apparent. In the nearby residential complex, hardly a single structure had escaped damage. At the impact site, several craters punctured the granite mountainside, and the resulting dirt and rocks had buried the railway line below. Just 200 feet to the east of the epicentre, the American hotel and a larger dormitory for Chinese specialists bore the brunt of the blast, though both buildings still stood. But a barbershop and a small market in front of them were flattened,” Zak described in his article. Inside the hotel, every door, window, and piece of furniture was destroyed. “There were holes in the walls,” Campbell recalled. He also noted that a monument to ancient Chinese rocketry in a little park in front of the hotel, had been blown off its pedestal. The diary-keeping engineer also described the damage of the nearby village. The passengers were horrified by what they saw. “Every house for several hundred meters was levelled,” he wrote.

According to the article, Campbell did not see human casualties but the Americans had suspicions. The night before launch, when he was in a van going from the hotel to the Satellite Processing Building, Campbell saw many dozens, if not hundreds, of people gathering outside the centre’s main gate. After the accident, when he returned to the residential area, just inside the gate, Campbell saw hundreds of Chinese soldiers and military vehicles were flooding into the area. They were suspected of removing bodies. Zak also mentioned in his article that eyewitnesses in Xichang described many flatbed trucks carrying what appeared to be covered human remains to the military base and hospitals in the town, along with dozens of ambulances. However, the eyewitnesses are unnamed and the contents of the trucks are purely speculation.

Shaking the sky

It was more than seven years after the accident when the first witness report appeared in the Chinese media. In July 2003, Dajiang Weekly, a publication in Jiangxi Province, had a report based on an interview with the CCTV journalist Zhang Heng, who was in charge of the live broadcast that night. According to Zhang Heng, he had planned to go to the launch pad, but due to an interview the next morning, he had to go to the Mission Command and Control Centre (MCCC) instead. He arrived there at 2:00 am and started broadcasting at T-5 minutes. However, the countdown was interrupted at T-59 seconds. He was told that there was a problem but he never knew what exactly it was. The liftoff was followed by a burst of applause. But Zhang felt that the rocket seemed drunk as it ascended slowly. The applause stopped as everyone stared at the screen on which the rocket was turning horizontal. They saw it dive to the ground with a bright flash. Seconds later, came a horrid thundering and violent shaking. The control room was suddenly in darkness. A few minutes later, lighting recovered.

Shortly afterwards, CCTV 4 cameraman Lu Xiaobing came in, with his face blanched. Lu was shooting the launch on the roof. He was flipped into the air by the violent shock wave, but he never stopped the filming. His video showed a giant mushroom cloud rising from the hill. Later, the vice-commander of the launch base came and said the crash site was at a hillside to the right of the main gate. He also said that some local houses were damaged and seven people were killed. Zhang was not allowed to leave the hall until 6:00. When he was back to his dormitory, he found the glass in some windows broken. At noon, he was notified that he could take the plane back to Beijing at 15:00.

Wang Yimu, author of the above report, republished the article on his blog on August 11, 2009, with a few more details. However, what the vice-commander said became “several people were killed”.

Chinese witnesses talking in the TV documentary Shaking the Sky. Top from the left: Wang Zhiren, He Zhuming. Bottom from the left: Yu Menglun, Cheng Jiapei. (credit: CCTV) |

In October 2003, days before the historic Shenzhou 5 mission, CCTV started to broadcast a 10-episode documentary series, “Shaking the Sky”, about the Chinese space programme. Its sixth episode, “Space is Not Dreaming”, is mostly about the CZ-3B accident in 1996. It was so far the most detailed record about the disaster. Many who were involved in the launch were interviewed and talked about their unforgettable experiences:

Wang Zhiren (Cryogenic Engine Expert of CALT): I looked up. But nothing went up. Suddenly, it came almost horizontally. What a trajectory!… Something must be wrong, we have to stay down. Luckily there was a drainage ditch under foot, about one Chi wide and one Chi in depth (Chi: Chinese traditional length unit, roughly equivalent to feet). We lay in it. Immediately it exploded. Then came the shock wave, like a strong wind. I remember my hair was caught and everything else like dirt, grass, leaves, blew over my head. Then the second bang… Back to our dormitory, looking around the building, doors, windows, all was gone. Glass fragments were everywhere. Later we were told to take the suitcase and leave as soon as possible.

| “In my department, a classmate of mine died. Two were seriously injured and nearly died.” |

He Zhuming (Deputy Chief Designer of CZ-3B, CALT): We knew there were some special issues in the (inertial) platform. But finally it was replaced and passed testing. Testing at the launch site was also quite smooth. We didn’t feel anything wrong and all were confident… That bang was very loud. We felt the shaking even in the bunker… Half of the hill was blown up. The Coordination Building (a building used as office and dormitory by the launch crew) where we lived was in ruins. People sat on the ground like refugees… At about 5 or 6 o’clock, it was heard that someone was killed… The shock wave broke the windows. The glass fragments hit the head of the victim who then bled to death. Two in the launch crew died. I heard that two or three villagers were also killed.

Yu Menglun (Trajectory Expert of CALT): All of us there didn’t know what to do… (narrator: unfortunately, a Senior Engineer who designs trajectory for the rocket became a victim) He lived at the ground floor. Because the launch time was at midnight after two o’clock, we discussed after dinner where we go to watch the launch. The proposal was the roof of the hostel where it has better views. Sun Shijie and the other three left their rooms together and went upstairs. He (the dead) was at the first. At mid of the stairs, the rocket exploded. The shock wave blew him off the staircase, threw him from the window, and dropped him on the ground… We both worked in the field of trajectory and have rare opportunity to watch launch. Normally we are in the control room. But during that launch, there seemed no much work for us. I discussed with him to watch launch outside and to find a place for it. We made a deal. But later I got a call from the launch pad. They had something to process and needed me to come there. I went before launch. As a result, I avoided the disaster. If I were with him, today I would…

Chen Zhenguan (CALT researcher on rocket mechanical environment): I was with Academician Yu (Menglun)… This is the hill. There is the launch pad. And this is the road. It came horizontally along the road. It looked really horrified… There are many hills… If it had avoided this hill and continued to fly along the road, it would be much dreadful. That’s the Mission Control Centre where there were many visitors. You often see it on TV. There were many people, many experts. If the explosion were there, that would be very terrible.

Cheng Jiapei (CALT designer on control system): In my department, a classmate of mine died. Two were seriously injured and nearly died. There were 3 or 4 cuts on his face. His neck artery was broken. The solider pressed on the cut all the way to Xichang City where it was finally stitched… It’s the first time our own people from the First Department (of CALT) died at the launch site.

Other video screenshots captured from “Shaking the Sky”. Top from the left: Intelsat 708 contract signing ceremony, Intelsat 708 transported to the launch pad. Bottom from the left: People in the control room in shock (on the left is Hu Shixiang, Director of the launch site by that time), last moment in the control room before the rocket’s explosion (credit: CCTV) |

More Chinese witnesses

Since 2003, there have been a few more witness reports in the Chinese media, providing additional details about the accident.

Shi Wei, the former Beijing Youth Daily journalist, now the Deputy Editor in Chief of the Daily, posted detailed reminiscences on his Sina blog on February 14, 2006, on the eve of the 10th anniversary of the tragedy.

Shi’s account started from the last afternoon before launch. At 15:00, or T-12 hours, the two-kilometer-long main road from the residential area to the launch pad had already been closely guarded. Two documents, the Pre-launch Evacuation Plan and the Mission Rescue Plan, were distributed to all teams. He remembered that the veterans comforted him as saying all these are just routine. Shi arrived at the frontier Launch Command Centre (LCC) near the launch pad at 23:00. At 2:00, a siren warning filled the air. A bus took the people to be evacuated to a safe place down in the valley. At 2:30 and 2:45, more were evacuated. He saw the lift-off and the rocket’s weird turning on the big screen. Almost at the same time when he heard a big bang like a dull thunder from far away, he felt the ground shake. The big screen flickered and all lights, except for the emergency lamps, went out. Long Lehao, Chief Designer of the CZ-3B launcher, stood up slowly. His face was unable to be seen clearly in the dim light. When the shock wave came, Shi Wei felt pressure in his ears. He was given a wet towel that was prepared as an emergency measure before launch. Covered with a wet towel on his face, Shi Wei went outdoors. This was 3:20. He saw the empty launch pad under starlight. Soon after, someone came from the impact site. When asked about the situation, the guy bit his lips and said, “Too bad,” with tears in his eyes. Shi Wei also recorded a detail in his article that when reporting to Beijing, the officer at the launch pad mentioned the location of the rocket falling down: on the side of the Coordination Building.

| “I would like to take this opportunity to lament Comrade Qian Zhiying and Yang Linzhen who died in the line of duty on 15 February 1996,” Liang said in a 2012 speech. This was the first time names of the dead were disclosed. |

At 4:50, two buses came to take the people away from the launch pad. Shi Wei noticed that all windows of the buses were gone and glass fragments were scattered everywhere inside the buses. At 6:30, most people, roughly a few hundred, were back to the residential area at the main gate and gathered near the Coordination Building. They were ordered to rescue as many documents and important materials from the building as possible. The building still stood there in morning sunshine. But all its windows, doors, and balconies were torn off. The saved material was packed in a number of green wooden boxes. Around noon, military trucks came and transferred these boxes to another location. At 14:00, the stranded people were moved to Xichang City in three groups. Long Lehao was in the last group. Later the same day, three China United Airlines planes carried all the people back to Beijing.

In March 2008, the Chinese version of National Geographic magazine published an article on the history of China’s launch sites. The author is Liang Dongyuan, a writer and also an insider of the Chinese space program who has published a series of articles and books. What he described about the CZ-3B accident in this article, which mostly happened in the MCCC, is quite similar to the story told by the CCTV journalist in 2003. For example, the T-59 second hold during final countdown and the casualties message from the vice-commander. But in Liang’s article, there was no exact casualty number. What the vice-commander said was that a quick check immediately after the accident concluded that several people, including a space technician who refused to be evacuated, were killed.

Geng Kun, the China Great Wall spokeswoman since 1997, provided more detail in an article published in July 2010. In the aftermath of the accident, China Great Wall was responsible for customer communication and arrangements for the on-site investigation by the insurance companies. Geng described what she saw at the main gate shortly after the accident. She was touched by a young guard who saluted to her and helped her vehicle pass through the gate. He looked obviously injured as there was blood on his face. Fortunately, the name of the guard can be identified in a story about his heroic deeds on the official China Military web site (Chinamil.com.cn). Ren Jianjun, the guard, was at his post just about 30 meters away from where the rocket exploded. He was thrown into a ditch of water by the shock wave and injured. But he persisted in his duty helping people and vehicles going through the gate. Four and half hours later at 7:30, he was sent to hospital. Today, he still works in XSLC.

The most recent information about the accident was revealed in a CCTV programme on April 23, 2012. The TV documentary was about 50 launches of the CZ-3A series (it includes CZ-3A, 3B, and 3C). It recorded the commemorative meeting held on the same day of the 50th launch, the ApStar 7 launch, on March 31, 2012. Liang Xiaohong, the Party Head of CALT, made an address. “I would like to take this opportunity to lament Comrade Qian Zhiying and Yang Linzhen who died in the line of duty on 15 February 1996,” Liang said. This was the first time names of the dead were disclosed.