Gambling with a Space FenceAn analysis of the decision to shut down the Air Force Space Surveillance Fence<< page 1: budget, authorizations, and appropriations Part 3: The Space Fence of the futureThe August 2013 AFSPC press release announcing the shutdown of the AFSSS contains a quote from Gen. Shelton on the confusion that often happens between the existing AFSSS “space fence” and the new S-Band Space Fence that the US Air Force plans to procure. That confusion is understandable and largely due to the decision made by AFSPC to give virtually the same name to what are in reality two very different systems with very different capabilities. They should be viewed more as an existing system and a completely new one, not an existing system and its upgrade.

At one time, however, there was going to be an upgrade to the AFSSS. Before transferring ownership of the NAVSPASUR to the Air Force, the Navy had already begun plans for a program to upgrade it. In 2002, Raytheon was awarded a contract for the modernization and upgrade of the NAVSPASUR. This contract included replacing the current VHF transmitters at 216.98 MHz with S-Band transmitters at 2.4 GHz. These modifications would dramatically improve the system’s ability and allow it to track objects as small as five centimeters in size, making it the most capable sensor in the SSN for tracking small objects. This upgrade was due to be completed by the end of 2004 for a total cost of less than $400 million in FY03 dollars (equivalent to $520 million in FY13 dollars). However, the transfer of ownership of the NAVSPASUR from the Navy to the Air Force between 2003 and 2004 disrupted these plans and they fell behind schedule. The Air Force rescinded Raytheon’s original contract and significantly reduced the budget allocations for the now renamed AFSSS in 2005, 2006, and 2008. In 2006, it appears that the Air Force had a change of heart and decided to revisit upgrading the AFSSS, but now starting from scratch. In June 2006, the Air Force issued a formal Request for Proposal (RFP) for a Concept Studies Phase for the AFSSS upgrade, including a Risk Reduction contract effort between FY05 to FY07. The RFP outlined a schedule that included system development, production, and fielding phases beginning in FY08, and award of the development contract award early that year. The RFP stated that delivery of the Initial Operational Capability (IOC) of the upgraded Space Fence was expected in the FY13–14 time frame. Raytheon completed the Risk Reduction phase in September 2006, but the program ran into more schedule slips. The initial contract award for the concept development phase was not awarded until July 2009. Contracts in the amount of $30 million each were given to three companies—Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman—for system design review, plans trades analysis and data, systems engineering planning, architecture planning, and prototyping. The three companies would then compete in the second phase to develop preliminary designs. Only two companies would win these contracts, expected to be awarded in April 2011. The final procurement contract to build the actual system was expected to be awarded to the winning company in 2012. By this time, the Air Force’s plan for the new S-Band Space Fence was radically different than the original Navy plan. Instead of upgrading existing AFSSS sites located in the United States, the Air Force plan called for the construction of three new “geographically separated” radar installations. Locations under consideration included Australia and the Pacific. Instead of multiple receiver and transmitters strung out in a long line across a continent, the new design called for a single receiver and transmitter located at each site. Rumors also circulated that the new design would also include pulsed radars at each site to actively track individual objects as well as maintain a massive detection fence.

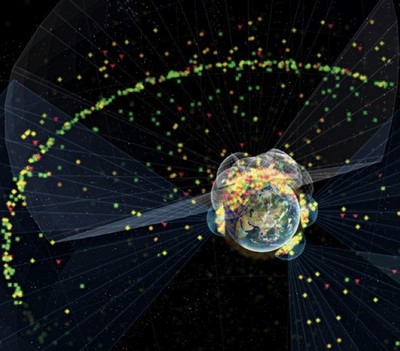

This new plan would significantly upgrade the usefulness of the new S-Band Space Fence. Not only would it be able to track an estimated 100,000 small space objects that are not tracked by any of the current radars, but the new locations being considered would vastly improve the geographic coverage of the SSN. With the exception of the radar on Ascension Island, all of the sensors in the SSN are currently located in the Northern Hemisphere. The vast majority of the radars in the SSN are concentrated near the North Pole and the outer perimeter of the United States as a result of their missile warning heritage. This overabundance of tracking coverage in the Northern Hemisphere results in more errors estimating the portion of objects’ orbits over the Southern Hemisphere, long gaps in tracking for objects in certain orbits (including some types of launches from China), and significant difficulty in tracking objects in certain rapidly decaying orbits. However, this new plan also came with a significant increase in cost, from the Navy’s original estimate of $400 million in FY03 dollars to an estimated $1 billion in FY09 dollars ($508 million and $1.1 billion in FY13 dollars, respectively). Of this $1 billion, $350 million would be spent on concept development using RDT&E funds to figure out how to make the system work. As the concept development phase progressed, costs continued to increase and the IOC continued to slip. In 2010, an Air Force press release stated that the total program would now cost an estimated $3.5 billion, while bragging that this was a “savings” of $3–4 billion in total lifecycle costs. This massive increase in costs was largely due to the technology not quite being ready for what the Air Force wanted to do. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report issued in 2011 stated that the initial site for the S-Band Space Fence had five critical technologies that were immature, each with a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of 4 or 5. The same GAO report estimates that the total life cycle of the program cost could be as much as $6 billion in FY11 dollars. By 2013, a new GAO report on the S-Band Fence program showed some signs of improvement. Total program costs had been reduced to a little more than $2 billion in FY13 dollars, including $1.2 billion in RDT&E costs and $832 million in actual procurement. These costs are double the estimate of overall program cost in 2009 and nearly triple the estimated cost for concept development, but significantly lower than just a couple years earlier. However, the 2013 GAO report also notes that these cost savings were realized in large part by procuring two, not three, geographically distributed S-Band radars. The first site is planned for installation on Kwajalein Atoll in the South Pacific, likely due to its geographic location, existing communications infrastructure, and heritage of radar development and operations. Tentative plans exist for a second site to be placed in Western Australia, but it remains to be seen if additional cost growth will further reduce the number of sites to just one. As it currently stands, there is uncertainty in when exactly the S-Band Space Fence program will finally deliver operational capability. Under the current FY14 budget scenario, it appears that the funding for the S-Band Space Fence will go through Congress mostly intact. Both the House and Senate markup of the FY14 NDAA contain the full amount of $400 million the US Air Force is requesting for Space Situational Awareness Systems, which includes the FY14 funding for the procurement of the S-Band Fence. The Senate FY14 Defense Appropriations Bill also includes the full amount. However, the House FY14 Defense Appropriations bill contains a $50 million reduction to the request, with the justification given as “a one year schedule delay”. Remarks made by General Shelton suggest that this delay was the result of funding decisions made by the Pentagon, not Congress.

The decision has resulted in the delay of yet another year of the award of the final procurement contract. As it now stands, the contract will be awarded in March 2014 and IOC of the first S-Band Fence on Kwajalein is slated for 2018. However, what capability those funds will buy is still in question. Rumors are that the S-Band Space Fence is facing another requirements modification that could mean the loss of the ability to do uncued detection of objects in MEO, leaving it only capable of doing uncued detection of objects in LEO. If this happens, it would mean a significant step backwards in broad area surveillance capabilities from the current AFSSS. Part 4: Sacrifices at the altar of Pentagon budget politicsThus far, this article has looked at the technical capability of the existing AFSSS and what impact its shutdown would have on space surveillance, the current budget situation for continued AFSSS operations, and the status of the new, planned S-Band Space Fence. None of this has revealed a precise answer as to why AFSPC has announced the shutdown. While closing down the AFSSS would not have a significant impact on the ability of the US military to accurately track medium to large-sized space objects, it would degrade the uncued tracking capability and overall situational awareness of the SSN. Moreover, the cost savings of $14 million are miniscule compared to the cost of operating other sensors in the SSN, plus the Air Force FY14 budget as it current stands in Congress includes funds to keep the AFSSS operational. All indications are that those funds will be approved by Congress. The only remaining possibility is that there are plans in motion behind the scenes that undercut the FY14 budget scenario. While it is true that none of the current budget planning includes sequestration, the Budget Control Act of 2011 remains the law of the land and there appears to be no progress on a political deal between the White House and Congress to undo it. Thus, despite the great efforts the Pentagon, Congress, and the White House are taking to pretend that sequestration doesn’t exist, the Pentagon is also quietly making plans for what happens when it does get enforced. The final contract award for procurement of the S-Band Space Fence on Kwajalein was put on hold earlier this year pending the completion of the Strategic Choices and Management Review (SCMR) by the Pentagon. The SCMR examined how budget cuts of various levels will impact the Department of Defense and its mission and, in particular, what impact sequestration will have to major procurement programs. The SCMR looked at three levels of cuts: the existing $100 billion in voluntary cuts over 10 years, a middle-road scenario where a deal between the White House and Congress to end sequestration results in cuts of $300 billion over ten years, and a “worst case” scenario where there is no deal and the Pentagon is required to undertake the entire $500 billion in cuts over ten years imposed by sequestration. Although the SCMR did not make any specific decisions, it did frame the choices DoD must make depending on the level of funding Congress appropriates. Moreover, this level of appropriation may change drastically depending on the negotiations between the White House and Congress over sequestration this fall. Thus, it is possible that AFSPC is canceling the AFSSS in anticipation of budget cuts yet to come as a result of the sequestration negotiations and the choices they will force the Pentagon to make. Aside from the paltry direct cost savings, eliminating the AFSSS allows AFPSC to make two arguments in support of the S-Band Space Fence as one of the procurement programs that should remain funded despite those cuts. One, that it is wholly committed to the S-Band Space Fence as the cornerstone of improving space surveillance and SSA. Two, that the existing AFSSS is too old and outdated to be useful, making the new S-Band Space Fence is even more critically important to protecting the hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of US space assets that are a vital component of US national security. If that is the case, then it’s likely that the target AFPSC is trying to influence is the Pentagon and not Congress. The new S-Band Space Fence is not a high-profile enough program to attract significant Congressional attention. While large in size for a space surveillance program, it is tiny compared to other major defense procurement programs. Space surveillance and SSA are also not issues that attract a lot of special interest groups. Absent the money or special interests, it is highly unlikely that Congress will not have the political motivation one way or the other to affect the S-Band Space Fence. That means the decision over whether or not to keep the S-Band Space Fence alive will be made in the Pentagon and the task of AFSPC is to ensure that it has a strong enough case to keep it above the redline. From the perspective of space surveillance and SSA, it is easy to see why AFSPC wants the S-Band Space Fence so badly. The current SSN does a good job of tracking the 23,000 or so objects larger than 10 centimeters, which allows the US military to predict potential collisions between active satellites and those larger debris objects and warn satellite operators. But they are effectively blind to the estimated 480,000 smaller objects between 1 and 10 centimeters (0.4 and 4 inches) orbiting the Earth. Those objects are too small for enough of the current SSN sensors to track reliably, and represent a significant collision risk to active satellites that currently cannot be protected against. A new S-Band Space Fence that can detect some portion of those objects smaller than 10 centimeters would go a long ways to improving the ability to protect satellites from collision that could damage or destroy them, as well as deliver a number of national security benefits.

It may be that this gamble will pay off and the end result will be an S-Band Space Fence that significantly enhances the space surveillance and SSA capability of the US military in the near future. But it is a gamble, and one where AFSPC has clearly made a specific choice to pursue a shiny new toy with lots of promise and excluded other options. These excluded options include upgrading the existing AFSSS, which would not only extend its life, but also increase its accuracy and sensitivity to small objects. Estimates from the AFSSS Program Office are that these can be done for around $300–400 million dollars and at little technical risk, although they will not deliver the same performance as what the new S-Band Space Fence promises or the additional geographic coverage. Other excluded options include working with other countries or the commercial sector to find other ways of augmenting the SSN’s capabilities with outside tracking data, an option that many in the US military actively shun. A significant factor in the decision to pursue the S-Band Space Fence option is the culture of AFSPC itself. For decades, its mission has been on space surveillance and the primary metric by which it measures mission performance has been accuracy of tracking data and element sets. This includes having complete control over the sensor that collects the data so that it can be fully understood and properly calibrated. Data from sensors outside the control of AFSPC are generally shunned, as they could have errors or deficiencies that degrade the entire data set. Although there are techniques that have been developed in other fields for handling this problem, they are not generally recognized or practiced by the space surveillance community at AFSPC. As is always the case, the metrics that are used to measure performance shape the decisions that are made based on those metrics. The emphasis on accuracy may come at the expense of wide-area surveillance or situational awareness, which is a different metric by which one could measure space surveillance capability. It may also be a metric that other users of SSA data outside of AFSPC value highly. Another important cultural factor playing into the decision to shut down the AFSSS is the “not bought here” factor. The existing AFSSS is an old, legacy system and it was one designed and developed by the Navy. It works under a completely different operating concept from all the other radars in the SSN. The existing software and processing algorithms at the JSpOC have significant difficulties with angles-only observations and are optimized for radar observations that have range information. The alternate control center at Dahlgren does have the software and processing algorithms to handle mass amounts of angle-only obs, but it too is largely shunned by AFPSC because it is also an old, legacy system that was “not bought here.” There is one very important element of risk in the gamble by AFSPC to bet the future on the S-Band Space Fence that needs to be kept in mind: JMS. Also a very troubled acquisition program, JMS is slated to replace the main computing and IT systems at the JSpOC. Without it, the S-Band Space Fence is useless, as the existing computing systems cannot handle the volume of observations or increased number of catalog objects that S-Band Space Fence will deliver. The probability that JMS will be in place in time is low. The Air Force has undertaken multiple programs over the last twelve years in an attempt to replace the current computing systems, all of which failed. AFSPC announced in 2011 that it was reassessing its strategy for JMS yet again, calling into question whether or not it can finally be the program that succeeds. Looking back at the entire situation reveals a saga that could be fit for Hollywood. The Navy’s original modest plan for an S-Band upgrade was thrown asunder by a transfer to the Air Force, which from the beginning is skeptical of the Navy’s plan and the worth of its adopted child. This led to years of turmoil and a budgetary see-saw, ultimately peaking with a grand vision to wipe the slate clean and replace the old, decrepit system with three new cutting-edge pieces of technology. And then, of course, is the fall from grace, with AFSPC’s struggle to salvage what it can of that grand vision in the face of harsh budget reality. As we reach the climax of the story, foreboding drums sound in the distance to announce the arrival of yet another threat… One wonders what the situation would be like now if the Navy had retained control and finished the original S-Band upgrade in 2005. It would not have been as capable as what the Air Force envisions for the entirely new S-Band Space Fence nor added to the geographic coverage of the SSN, but it would have been something that would have contributed to the mission by improving the ability to track smaller objects. As it stands, the Air Force has already spent $250 million and nearly ten years trying to get something better, perhaps at the expense of good enough. Only time will tell whether or not this gamble pays off and AFSPC’s dogged pursuit of the new S-Band Space Fence instead of other options was the correct decision. In the meantime, it should be noted that the result will have a much bigger impact than just on the ability of the US military to perform the space surveillance mission. As it stands, the entire world is highly dependent on the US military for SSA and in particular the information necessary to avoid collisions in space. The United States has quietly taken steps to reinforce this reliance because it allows the US government to control the flow of information and thus help protect some of its own activities in space. However, should the Air Force’s optimism with the S-Band Space Fence and JMS prove unfounded, it could have widespread and long-lasting consequences for both faith in the US military’s SSA capabilities and the long-term sustainability of the space environment itself. Home |

|