Review: The Visioneersby Jeff Foust

|

| O’Neill was a “visioneer” of the first order: he envisioned a future where thousands, even millions, of people lived and worked in space, and took strides to both develop its technological foundations and to promote it to broader audiences. |

Many of those lured by the high-wattage stars to see Elysium may have gotten their first exposure to the concept of space colonies, which had remained largely out public view since their heyday in the 1970s. On one hand, they were treated to stunning visuals that looked, in may respects, like updated versions of the original 70s-era illustrations of what life would be like in space colonies (see “Futures imperfect”, The Space Review, May 20, 2013). On the other, though, the idea of a space colony as a place only for the wealthy—and as a refuge from a polluted Earth—seemed at odds with the more utopian visions of space colonies from that earlier era.

That clash of visions of the future prompted the National Space Society (NSS) to issue a press release late last month regarding space colonies. “NSS is happy that space settlements are beginning to appear in popular culture such as the recent motion picture Elysium,” it stated, then added that “we would like movie viewers to keep in mind that the tyrannical government depicted in the movie does not represent the path of humans in space envisioned by the NSS and its thousands of members.”

While it seems unlikely that anyone thought the NSS endorsed tyranny, even on a space colony, it’s easy to understand why the organization would be particularly protective of the vision of space colonies. The NSS emerged over a quarter-century ago from the merger of two very different space organizations: the more establishment National Space Institute and the L5 Society, a grassroots organization founded by those who had become attracted to the concepts of a Princeton University professor named Gerard K. O’Neill to establish giant habitats in space to make use of the boundless material and energy resources there.

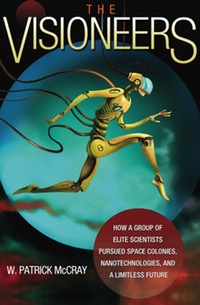

O’Neill is a central figure in the book The Visioneers by Patrick McCray, a historian at the University of California Santa Barbara. McCray defines “visioneering” as “developing a broad and comprehensive vision for how the future might be radically changed by technology, doing research and engineering to advance this vision, and promoting one’s ideas to the public and policy makers in the hopes of generating attention and perhaps even realization.” O’Neill, using that definition, was a visioneer of the first order: he envisioned a future where thousands, even millions, of people lived and worked in space, and took strides to both develop its technological foundations and to promote it to broader audiences.

| O’Neill was convinced that an ambitious program for humans in space would counter the pessimism, irrationality, and cultural stagnation he feared would continue to grow with society’s rejection of science and technology,” McCray writes. |

Much of the first part of the book traces the development and rise of O’Neill’s space colony vision from a classroom exercise at Princeton (“Is the surface of a planet the right place for an expanding technological civilization?” he famously asked his students) that was fleshed out over the next several years to designs for cylinders and toruses built using lunar resources at the Earth-Moon L5 Lagrange point. While working on the designs of space colonies and enabling technologies like mass drivers, he was also working to promote the concept, including a seminal 1974 article in Physics Today that helped trigger broader interest in the concept.

That space colony visioneering was driven by the pessimism of the era. “O’Neill was convinced that an ambitious program for humans in space would counter the pessimism, irrationality, and cultural stagnation he feared would continue to grow with society’s rejection of science and technology,” McCray writes. This pessimism was embodied by The Limits to Growth, a 1972 book that warned of societal collapse as civilization exhausted the Earth’s resources. That book, McCray states, was particularly compelling to O’Neill and other space colony advocates, even after the book was roundly criticized for an oversimplified, overly pessimistic forecast for humanity’s future.

The space colony concept reached its “apogee,” McCray argues, in 1977, with the publication of O’Neill’s book The High Frontier that generated more publicity, as well as a segment about space colonization on 60 Minutes. The L5 Society was growing as well, promoting the vision of humans living in space (although, McCray notes, O’Neill had a complex relationship with the organization, not to mention another famous promoter of space colonies, counterculture guru Timothy O’Leary.) O’Neill created the Space Studies Institute to further his work on technologies like mass drivers, including a small amount of funding from NASA.

So what happened to that vision of space colonies that, in the late ’70s, appeared to be on the upswing—“L5 by ’95” was a clarion call of the L5 Society at the time? McCray doesn’t devote as much attention to this as he does the rise of the concept. Proponents like the L5 Society shifted their attention to space commercialization and militarization in the early 1980s, the latter in particular with the introduction of the Strategic Defense Initiative by the Reagan Administration; a “gradual drift away from a counterculture-flavored enthusiasm for celestial communes where one could pursue alternative lifestyle choices,” McCray writes. O’Neill himself focused his energies on a commercial space venture, Geostar, before passing away in 1992. And, certainly, technology and economics played a role: those early space colony concepts were predicated on plans for frequent, low-cost space access the Space Shuttle was expected at the time to provide, but failed to achieve. Even the pessimism of the 1970s faded away by the ’80s and its “Morning in America.”

| While the idea of space colonies faded, O’Neill’s influence on space in general remains, McCray argues, seeing his influence on contemporary NewSpace commercial space ventures. |

The Visioneers is not a book solely about O’Neill and space colonies: the second half of the book looks at another “visioneer” in another field, K. Eric Drexler and nanotechnology. However, the two are closely linked. Drexler was something of a protégé of O’Neill, studying space colony concepts while a student at MIT in the ’70s, only later deciding to pursue “molecular engineering,” which later became known as nanotechnology. Drexler also found an audience of people receptive to nanotechnology and its benefits in the same community of space activists who had advocated for space colonies. However, Drexler’s vision of nanotechnology—self-replicating machines that could manipulate individual atoms—is a far cry from what is generally considered nanotech today, and a vision that remains unrealized.

While the idea of space colonies faded, O’Neill’s influence on space in general remains, McCray argues, seeing his influence on contemporary NewSpace commercial space ventures. “Here, we find O’Neill’s influence, given his belief that space should not be a government-run program but a place,” he writes. “This shift in perspective, so essential to O’Neill’s plan for the humanization of space, contributed to the NewSpace movement’s foundation.” (Not mentioned in the book, but supporting his thesis, is the fact that one of those NewSpace entrepreneurs, Jeff Bezos, spoke in support of space colonies in his 1982 high school valedictory speech.) To this day, some space activists who align themselves with NewSpace refer to themselves and others inspired by O’Neill as “Gerry’s Kids.”

As Elysium has demonstrated, the idea of the space colony has not completely faded into history. In fact, the cover story of the latest issue of Ad Astra, the NSS’s quarterly magazine, features a new space colony design called Kalpana One (named after STS-107 astronaut Kalpana Chawla.) “Kalpana One is as small as we dared make it,” Al Globus writes in the article, but it’s still huge: a cylinder 500 meters in diameter and 325 meters long, big enough on the inside to support 3,000 people with room for a soccer field, baseball diamond, and even a golf course. There’s virtually no discussion in the article, though, about how to build it, including how long it would take and how much it would cost. Even the boldest of NewSpace entrepreneurs, Elon Musk, has set a long-term goal not of an L5 space colony, but instead a Martian settlement. The vision of space colonies remains, four decades after its development by O’Neill, but it seems likely to remain just that—a vision, not a reality—for the indefinite future.