Inspiration Mars: from nonprofit venture to space policy adventureby Jeff Foust

|

| “It’s a good thing the SLS is being developed,” MacCallum said. “I didn’t frankly start off as an SLS supporter in this, and I came around to being one.” |

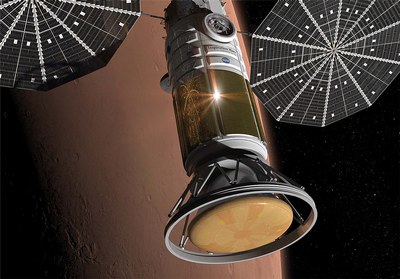

The concept Inspiration Mars published in the summary of a 60-day architecture study released on Wednesday, November 20, offered a very different approach to what they proposed in their earlier IEEE paper. (The full 580-page report can’t be released because of export control restrictions, Tito told reporters.) Their current baseline makes use of two separate launches. First, a Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket, presumably on its inaugural flight, places into orbit the “Vehicle Stack” for the mission, consisting of a modified Cygnus spacecraft that serves as the crew habitat, a service module, and an Orion spacecraft with an enhanced heat shield that the crew would use to return to Earth at the end of the mission. The stack would be launched into orbit attached to a new upper stage, the Dual Use Upper Stage (DUUS).

A second launch, using one of the commercial crew systems currently under development, would carry the two Inspiration Mars crewmembers. The commercial crew vehicle would dock with the vehicle stack and transfer the crewmembers over, then undock and return to Earth. The DUUS would fire its engines to place the spacecraft on its Mars flyby trajectory. At the end of its mission, 501 days later, the crew would board the Orion to return to Earth; it’s unclear from the summary if the rest of the spacecraft would burn up in the atmosphere or remain in its orbit around the Sun.

All of this would have to come together relatively quickly. According to the report, the launch window to enable this mission opens on Christmas Eve of 2017 and closes on January 4, 2018, less than two weeks later. “The short time period between today and the launch window is both an opportunity to show the world what America can do as well as a challenging constraint that touches every aspect of the mission,” the report states.

Taber MacCallum, program manager for the Inspiration Mars study, told reporters last week that the shift in architecture was driven by two factors. One was that the commercial systems they studied to do the mission “really didn’t come in with the kind of margins that gave us a good feeling about the risk associated with that,” he said, without going into greater detail. The other was their growing confidence that the SLS could do the job. “It’s a good thing the SLS is being developed,” he said. “We really came around to independently validating the need for SLS. I didn’t frankly start off as an SLS supporter in this, and I came around to being one.”

Although it’s not mentioned in the report summary, Tito and MacCallum said they are looking at a backup option if that end-of-2017 mission isn’t feasible. That backup option would use those launches to send a Mars flyby mission in late 2021 on a roundtrip 88 days longer than the 2018 mission, but would also feature a close flyby of Venus as well. That mission would have additional logistical challenges, as well as a greater radiation exposure to the crew for the longer mission, Tito noted.

Seeking a space policy shift

Bigger than the shift in launch vehicles and spacecraft, though, is the shift in the Inspiration Mars business model. When Tito and colleagues unveiled their plans in February, they billed this as a private mission that would be funded philanthropically, with perhaps the sale of media rights or other sponsorships. Government funding was not a major part of their approach. “There’s no expectation of any funding from NASA, other than purchasing data or performing experiments for NASA,” Tito said at a February 27 press conference announcing Inspiration Mars. “We have to raise the money from individuals.”

| “This has to be, first and foremost, a NASA mission,” MacCallum said. |

However, in his testimony before a hearing of the space subcommittee of the House Science Committee Wednesday morning, Tito said that he was asking for several hundred million dollars in additional funding for NASA to develop the capabilities to carry out the mission. That includes accelerating work on the DUUS, which NASA currently doesn’t plan to have ready until at least the early 2020s.

Tito, pressed about the cost of the mission at the House hearing, said he expected to be able to raise several hundred million dollars philanthropically once there was a commitment to carry out the mission. “It would cost the government about $700 million” on top of this private funding, he said, bringing the total cost to no more than $1 billion. (That figure, though, doesn’t appear to include the cost of the SLS, Orion, or other government systems already under development that the mission would make use of.)

At the hearing, one member asked if this mission was possible without the NASA contribution. “Are you suggesting that the mission couldn’t be undertaken without additional NASA funding?” asked Rep. Donna Edwards (D-MD), ranking member of the space subcommittee. “Right now, I don’t see a lot of evidence that money is available,” Tito responded.

“The way that we’re proposing this is that this is a NASA mission with a philanthropic partner contributing to the mission,” MacCallum told reporters. “This has to be, first and foremost, a NASA mission.”

While Inspiration Mars had long billed its concept as “A Mission for America,” this new turn made it clear they were seeking to influence national space policy by accelerating the date of a human Mars mission from the mid-2030s, as proposed by President Obama in 2010, to late this decade. “It will not be any easier, or any cheaper, to do in 20 years what can be done in five,” the report states. “By doing it now, moreover, we expand the range of what can be achieved and learned in the 2020’s and 2030’s.”

Tito matched the report’s carrot with a stick: if the US was unwilling to carry out a mission, even in the 2021 window, other nations would try. “Another country, almost surely China, will have seen our missed opportunity and taken the lead themselves,” Tito warned Congress. “May I offer a frank word to the subcommittee: the United States will carry out a flyby mission or we will watch as others do it. If America is every going to do a flyby mission of Mars, we’re going to have to do it in 2018.”

Later, in a teleconference with reporters, he played up a Russian threat to perform a mission, claiming that Russia was restarting work on the long-dormant Energia heavy-lift rocket to perform such a mission. “I think this mission is going to fly, one way or another, by the latest 2021,” he said. “The only question is, is it going to fly on an SLS or is it going to fly on an Energia?” He said, though, he had no evidence of Russian interest in pursuing such a mission beyond “educated guesswork.”

| “I think this mission is going to fly, one way or another, by the latest 2021,” Tito said. “The only question is, is it going to fly on an SLS or is it going to fly on an Energia?” |

The threat of Russia or China beating the US on a human Mars flyby mission appears to have done little so far to motivate policy makers to consider his plan. “The agency is willing to share technical and programmatic expertise with Inspiration Mars, but is unable to commit to sharing expenses with them,” NASA spokesman David Weaver said in a statement provided to media after the report’s release last week. “However, we remain open to further collaboration as their proposal and plans for a later mission develop.”

Tito said there was a short window for Congress and the White House to support the Inspiration Mars concept and still be able to launch at the end of 2017. “We have just a couple of months to get some signals that would indicate serious interest developing,” he said. He and MacCallum said they have been in touch with Congress and White House officials; on the latter, “we have had good discussions so far,” MacCallum said. Tito said later that an unnamed member of Congress would introduce a bill “in the next week or two” about the mission, but declined to name that member or members, or the contents of the bill.

Even if there was broad support for the revised Inspiration Mars concept—which, for now, doesn’t appear to exist—it would be difficult to get what would constitute a signification shift in human spaceflight policy through Congress in the next couple of months, given all of the other issues at both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. “More than any new federal funding for this mission – some might be needed, but not much – what NASA would require to carry out its part of the work is the freedom to direct existing funds to the enterprise,” the report argues. “This is a freedom that Congress can grant and the President can assure, as John F. Kennedy did to clear the bureaucratic path for Apollo.” But without the same geopolitical urgency that fueled Apollo, Inspiration Mars may have to set its sights on a 2021 mission, or something else entirely.