How to form the Lunar Development Corporation to implement the Moon Treatyby Vid Beldavs

|

| The lack of an internationally agreed-to regime for the commercial development of the Moon and other celestial bodies is arguably the most significant barrier to more rapid commercial development beyond Earth orbit. |

Many have pointed to the need for an international regime to enable commercial space development. The Moon Treaty was a serious attempt by the world community to address the need for an international regime for space resources based on agreements reached earlier with the Law of the Sea and the concept of Common Heritage of All Mankind. The Moon Treaty was negotiated in the context of the North-South divide marked by the poverty of developing countries that had votes in the UN and the increasing power of multinational corporations to control economic resources. Space advocacy constituencies in the US saw the Moon Treaty as a power grab by poor developing countries to claim space resources through the power of UN bureaucracies that they did not have the technical means to reach on their own.

The US did not sign nor ratify the Moon Treaty, and neither have any of the major spacefaring powers. However, the Moon Treaty has been signed and ratified by Australia, Austria, Belgium, Chile, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Mexico, Morocco, Netherlands, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Uruguay. France, Guatemala, India and Romania have signed the Treaty, but have not yet ratified it. As Michael Listner noted last year (see “The Moon Treaty: it isn’t dead yet”, The Space Review March 12, 2012):

Turkey’s accession to the Moon Treaty will give the accord strength not so much in terms of individual political strength, but through political strength in numbers. As those numbers grow, the “Big Three” could find that their influence as non-parties of the Moon Treaty will be challenged by a chorus of many smaller nations who are parties.

It is noteworthy that three members of the European Union have signed and ratified the Treaty while an additional two EU countries have signed, opening the possibility for the entire EU to agree to the Treaty to enhance and accelerate opportunities for space development of member states, as well as to enhance the large-scale developmental assistance programs of the EU towards African and other developing nations.

Today, China, India, and other countries that were poor and without major space programs in the 1970s have programs to explore the Moon and the rockets to get there. China’s Chang’e-3 lander is slated to land on the Moon on December 14. Russia has plans for an ambitious lunar base program and the EU, Japan, India, and South Korea have programs directed at lunar resources. The US, by contrast, has no serious Moon-directed program in its forward plan. Unless there is a dramatic shift in US space policy, the US will be trailing China, the EU, and others in lunar exploration and commercialization in the coming years. Even the entrepreneurial initiative of US firms represented by the Google Lunar X PRIZE is unlikely to meet GLXP goals by 2015 and lesser objectives are being substituted, even as the programs of China, India, Russia and the EU appear to be expanding.

| A number of companies have been formed to exploit lunar resources and more are on the drawing boards. This adds urgency to the lack of an international regime for commercial development of the Moon. |

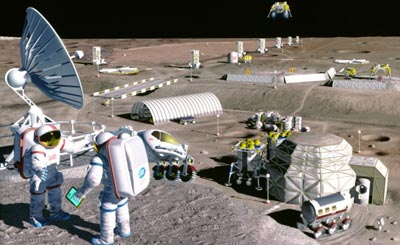

Exploration of the Moon by China, Russia, and others is being planned in a very different spirit from the NASA missions of the 20th century that were scientific in nature. Water and other valuable resources have been confirmed on the Moon. New programs have a focus on potential commercial and strategic exploitation. The Moon is the greatest mineral find in human history. Astronomically speaking the Moon is nearby, gravity is low, it has vacuum and very abundant materials from which things can be built that people need in space: solar power arrays, habitats, electronics, and soil and water for growing food and producing industrial chemicals.

A number of companies have been formed to exploit lunar resources and more are on the drawing boards. However, they all assume that a miracle of some kind will allow them to set up and start operations undisturbed by the dozens of other groups readying to do the same. This adds urgency to the lack of an international regime for commercial development of the Moon.

What are the options?

- Simply go to the Moon and start mining water or whatever is in your business plan and hope no one else sends robots that can mine better and faster. This is unlikely. If there is great wealth to develop there is no reason for the technically superior competitor to wait his turn.

- Wait for the UN to address the issue on its schedule and on its terms. Renegotiating the Moon Treaty will take too long. Whoever gets to the Moon first with mining technology will be in the catbird seat. With the US looking increasingly like a space laggard, this may become a very serious issue, notwithstanding the great work done earlier by NASA and being done by GLXP contenders.

- Try a better, simpler way.

The better, simpler way

The better, simpler way is to recognize the Moon Treaty for what it is: a rough framework that can be adapted to meet the requirements of commercial space development in a manner that can fit the priorities not only of developing nations, but also the leading spacefaring powers like the US, Russia, China, and the EU.

Here is one way how it can be done. Form the Lunar Development Corporation (LDC) with a mission to implement the Moon Treaty in a way that stimulates rapid commercial development of the Moon. The mere existence of the LDC would multiply the value of shares of all GLXP contenders and all other commercial space ventures with ambitions beyond Earth orbit. As LDC takes on increasingly significant roles, the market value of commercial space ventures will increase, so it will make sense for long-term investors to invest to increase the capabilities of LDC to simultaneously improve the prospects for their other commercial space investments.

LDC can be structured as an entity with part of its capital from private sources and the rest from countries that have ratified the Moon Treaty. The Moon Treaty is clearly in force only for the countries that have ratified it. However, as Michael Lister points out in his article, the treaty has not been tested in court, although each additional ratifying country increases the strength of the Treaty as an internationally legally binding act.

| As LDC takes on increasingly significant roles, the market value of commercial space ventures will increase, so it will make sense for long-term investors to invest to increase the capabilities of LDC to simultaneously improve the prospects for their other commercial space investments. |

The governing Board of LDC can be selected based on the balanced interests of ratifying states and private investors. Perhaps initially the governing board could include representatives from all of the countries that have ratified the Moon Treaty as of the date of the formal organization of LDC, with other later members joining and gaining board seating based on their capital contribution or other criteria as appropriate. A second body with veto powers based on majority vote could be structured to include representatives of all member countries. This structure would encourage private investors to take an ownership stake in LDC but also encourage countries to buy in so that they can have a seat at the table where decisions are made about commercial space development policies.

Initially, LDC functions could include the following:

- Develop and operate the Moon business incubator(s). Services such incubators could provide include electrical power, water and atmosphere, repair facilities for common equipment, habitat and workspace for incubator tenants, most likely involving a minimal staff not to exceed a prescribed number, perhaps five people. Power could be provided at a nominal cost in the startup period rising to full pricing over a period of time, likely five years. Only companies that have been chartered in countries that have ratified the Moon Treaty could become tenants in the Moon business incubator(s). Countries could financially sponsor companies chartered within their territory to become members of the Moon business incubator. Over time the services provided through the business incubator(s) could become utility services to companies or research institutes or tourist facilities operating on the Moon.

- Develop the guidelines, policies, and mechanisms for establishing resource claims on the Moon and for dispute resolution among all claimants. Only companies chartered in countries that have ratified the Moon Treaty could file legitimate claims to resources on the Moon.

- Form the Lunar Claims Office as a function of LDC to implement the resource claims and real property policies established by LDC.

- Establish an Arbitration Office to arbitrate among businesses legitimately operating on the Moon to further their commercial interests.

- Develop the guidelines, policies, and mechanisms for determining royalty payments to LDC from the utilization of the Moon and its resources for commercial benefit from firms legitimately operating on the Moon.

- Establish the Fund for Space Development whose revenues will initially come from investments by firms and by country members of LDC by virtue of the ratification of the Moon Treaty. After revenues begin to be generated by companies operating on the Moon under the structure of LDC, the royalty payments to LDC will comprise an increasing share of the Fund for Space Development.

- Develop the guidelines, policies, and mechanisms for allocating Fund for Space development monies to the operation of LDC and its functions such as the Moon Business Incubator(s) as well as furthering the space development interests of all signatories to the Moon Treaty.

Possible steps to form and fully realize the potential of LDC

Step One: Hold an organizational meeting to form LDC. Invite space entrepreneurs that can bring startup funds to start the LDC.

Step Two: Form LDC as a public private partnership with private capital and funding from member countries and governance shared between Moon Treaty-ratifying country members and space entrepreneur investors.

Step Three: Invite countries that have ratified the Moon Treaty, like Australia, to join LDC. Favorable terms could be offered to these early members. LDC could be chartered in Australia if these steps are coordinated with the timing of the G20 Summit in Australia in 2014.

Step Four: Hold conferences and task force meetings to develop elements of LDC operations with input from professionals and technical specialists with expert knowledge about space business conditions and other critical knowledge areas. Funding would be need for this.

Step Five: Present the LDC and its potential to the Australia G20 on November 15–16, 2014, in Brisbane, Australia. This potential could be demonstrated in scenarios covering business as usual to large-scale, lunar development as a global priority. Australia as a signatory of the Moon Treaty, together with Turkey, France, India, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico, could propose that the G20 commission a feasibility study of a large-scale, international space development program to address the global challenges of climate change, resource constraints, and employment with a focus on the LDC as the mechanism to manage the lunar development portion of the program. This feasibility study commissioned by the Australia G20 could be reported out at the Summit Conference of the Turkey G20 in 2015. (Note that Turkey has also ratified the Moon Treaty.) The proposed feasibility study would address how the large-scale investments in space development can address the global grand challenges and present an action plan for implementation through 2050.