Who framed Jade Rabbit?by Jeff Foust

|

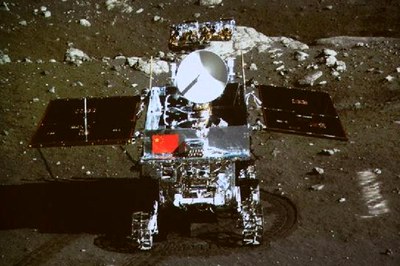

| “China’s first lunar rover, Yutu, could not be restored to full function on Monday as expected, and netizens mourned it on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like service,” read the Chinese report that triggered news of Yutu’s demise. |

If you were following the news last week, that appeared to be the case. On Wednesday, Western media reported that Yutu was dead, failing to revive after hibernating through the two-week lunar night. The next day, the story changed: Yutu was, in fact, alive, if not completely well. A miracle? Not exactly. Instead, the incident revealed both sloppiness in the Western media and a stubborn lack of openness by the Chinese government despite being more forthcoming earlier in the mission.

What triggered the initial wave of reports about Yutu’s apparent demise was a very brief report attributed to China Daily and published on a Chinese website called Ecns.cn. “Loss of lunar rover,” read the headline of the February 12 article, which offered only two sentences of explanation: “China’s first lunar rover, Yutu, could not be restored to full function on Monday as expected, and netizens mourned it on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like service. Yutu experienced mechanical problems on Jan 25 and has been unable to function since then.”

Despite the headline, the article did not say that Yutu was declared dead, only that an effort on Monday (February 10) to “restore full function” has not worked. Yutu is hardly the first spacecraft to encounter problems during a mission, and, in most cases, the media have not written off those missions as hastily. Moreover, the Chinese report’s second sentence claiming that the rover had been unable to function since January 25 made the problem sound more dire. Chinese media had reported that the rover suffered some kind of mechanical problem before going into a planned hibernation during the lunar night (the rover, being solar powered, can’t operate at night); some experts outside China speculated that the rover wasn’t able to fold up a panel to allow the rover to retain heat during the night. Even if the rover was working properly, though, there would have been a two-week gap in communications because of being in hibernation during the lunar night.

Nonetheless, Western media started writing their obituaries for Yutu based principally on that brief China Daily report. “Earth Bids China’s Yutu Moon Rover Farewell Forever!” declared Universe Today, one of the first news outlets outside China to report on the rover’s perceived demise (the headline and content have changed based on later developments, although the original headline can be seen in the article’s URL.) “China’s Jade Rabbit rover pronounced dead on the moon,” reported New Scientist. “Jade Rabbit lunar rover dies on moon,” announced the AFP news agency.

But even as Western media were still working on those articles about Yutu’s demise, other reports indicated that the rover wasn’t dead—at least, not yet. One Chinese report from late Wednesday Beijing time (13 hours ahead of North America’s Eastern Standard Time) indicated that the situation with Yutu was improving and that engineers were still working to restore its operations. A few hours later, the English-language Chinese publication Global Times reported the same, citing an anonymous source at mission control: “The little rabbit is getting better and shows some signs of awakening. Let's wait.” Yet the Yutu obits continued to appear.

It wasn’t until Thursday morning in China—Wednesday evening in North America—that the official Xinhua News Agency announced that Yutu was, in fact, operating, although not without problems. “Yutu has come back to life,” Pei Zhaoyu, mission spokesperson, said in the Xinhua account. “Now that it is still alive, the rover stands a chance of being saved.”

Xinhua went to great—and unintentionally hilarious—lengths on Twitter to get the news out that Yutu was alive. In one tweet it included the Twitter handles of a wide range of outlets to get their attention—including the satirical publication The Onion:

RT China's #moonrover #Yutu awake after troubled dormancy http://t.co/PJco3XwDiN @NASA @TheOnion @HuffingtonPost @BreakingNews @googlenews

— China Xinhua News (@XHNews) February 13, 2014In the Western media, the Yutu obits were replaced by stories of its resurrection of sorts. The BBC, for example, changed a story with the headline “Jade Rabbit rover ‘declared dead’” to “China’s Jade Rabbit lunar rover ‘could be saved’”. Yet, as recently as this weekend, Science News tweeted that Yutu had died, even though the article it linked to had been updated to indicate that contact with the rover had been restored:

China's lunar Yutu rover fails to connect with controllers. It's dead: http://t.co/IRfytSLIMq pic.twitter.com/FYThxG6ik9

— Science News (@ScienceNewsOrg) February 15, 2014It’s not clear why so many media outlets were so quick to report that the rover had died, based presumably on that initial, and cryptic, China Daily report, or continued to do so as both Chinese and English-language reports from official sources indicated that efforts to restore contact with the rover continued. Some, though, did get it right: The Planetary Society updated its blog post with developments, including a detection by amateur radio operators of a signal coming from Yutu, hours before they made it into other media reports.

| However, the Chinese government and official media have been far less forthcoming with information about the mission, including Yutu’s problems, since the landing in December. |

One usual excuse has been the reputation China’s space program has had for secrecy. Yet, the Chang’e-3/Yutu mission had been, at least in its early phases, remarkably open. Not only was the launch televised live (something it has done in the past for human spaceflight and other high-profile missions), so was the landing and rover deployment, something far more risky (see “It’s not bragging if you do it”, The Space Review, December 9, 2013.) That coverage looked remarkably like that for a NASA or other Western mission, from cameras mounted on the rocket to provide live video during ascent to the use of reporters and panels of experts to cover the launch and landing on China’s CCTV television network.

However, the Chinese government and official media have been far less forthcoming with information about the mission, including Yutu’s problems, since then. Thursday’s Xinhua report about Yutu mentions “mechanical issues” and “technical problems” with the rover, but offers no details about those problems. A report in late January, as the rover entered hibernation, referred to a “mechanical control abnormality” caused by the “complicated lunar surface environment,” but also offered no additional technical details.

There has been no official word from Xinhua or other Chinese sources about the status of Yutu since that early Thursday report that the rover was alive. That silence suggests engineers are finding it challenging to get the rover working again, at least to a point where they’re comfortable with making an official announcement about their progress. If that silence continues, speculation that Yutu has suffered what ultimately is a fatal malfunction will grow. Still, it might be wise for the media to be a little more careful the next time they try to write off Yutu.