Commercial crew, Crimea, and Congressby Jeff Foust

|

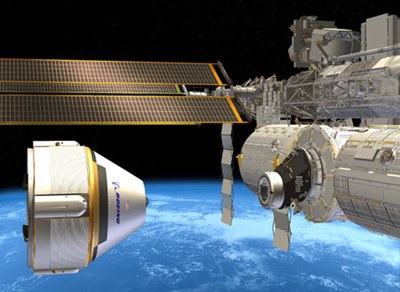

| Commercial crew efforts are in something of an extended period of transition, as companies complete work on their CCiCap awards and await NASA’s decision on CCtCap. |

What the events of the last several weeks have done, though, is provide another reminder of NASA’s ongoing efforts to develop an alternative to the Soyuz for crew access to the ISS. Much of that attention has been instigated by NASA itself, reminding people of its Commercial Crew Program to develop vehicles that can transport NASA astronauts to the ISS and serve other commercial markets as well. However, the program is not a near-term solution to current tensions, and Congress, so far, does not seem motivated to better support the program despite its concerns about reliance on Russia.

Commercial crew status report

For now, commercial crew efforts are in something of an extended period of transition. The three companies that currently have funded agreements with NASA as part of the Commercial Crew Integrated Capability (CCiCap) program—Boeing, Sierra Nevada, and SpaceX—are currently carrying out those agreements, with many of the milestones of those awards already completed. Meanwhile, those companies await NASA’s decision on proposals they submitted early this year for the next phase of the commercial crew effort, Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap).

Boeing is down to the last three milestones in its CCiCap award, said Chris Ferguson, director of crew and mission operations for the CST-100 spacecraft, in a presentation at the Space Tech Expo conference in Long Beach, California, on April 1. “We are on a path to critical design review coming up in July of this year,” he said, the final milestone in its CCiCap award.

Boeing has leveraged a considerable amount of flight-proven components for the CST-100 spacecraft, he said, aiding its development. “The spacecraft itself has a lot of legacy in space,” citing in particular space-tested and -qualified components of the CST-100’s avionics system. “It’s been really nice to pull an awful lot from off the shelf for the avionics suite.”

One tweak to the CST-100 design is the addition of solar cells to the base of the service module. Originally, Ferguson said, Boeing designed the spacecraft to be powered entirely by batteries, given its short free flight times—less than a day—to and from the ISS. Adding the solar panels to the base “allows us to tread water from an electrical perspective” and keep the batteries charged.

One other upcoming change with the CST-100 has to do with the spacecraft’s name itself. “We have absolutely wonderful ideas for a creative name,” he said. “I think you’ll see that after [CCtCap] contract award.”

Sierra Nevada, widely seen as the underdog in the commercial crew competition since it received a CCiCap award half the size of Boeing and SpaceX, is pressing ahead with development of its Dream Chaser lifting body vehicle. At Space Tech Expo, John Curry, senior director and Dream Chaser co-program manager, said the company had achieved 27 milestones total in its various commercial crew awards, from its initial Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) award to its ongoing CCiCap agreement.

One of those milestones was a free flight of a full-scale engineering test article of Dream Chaser last October at Edwards Air Force Base in California, the final milestone in its CCDev-2 agreement. While the vehicle skidded off the runway upon landing when one of the vehicle’s landing gear elements failed to deploy, both the company and NASA declared that test a success as the glide flight was intended to test the vehicle’s flight characteristics, and the landing gear used on it was different from that planned for the actual flight vehicle.

| “We have just four milestones left, only four, but they’re big ones,” said SpaceX’s Reisman. |

That test article is back at the company’s facilities in Colorado being upgraded for a new series of free flights. “We’re going to fly it again this coming fall with the orbital vehicle avionics, software, and guidance, navigation, and control, which is a big upgrade for us and accelerates the development of those systems,” Curry said. The first orbital Dream Chaser vehicle is currently under construction at the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, under an agreement between Sierra Nevada and Lockheed Martin.

Sierra Nevada has been aggressive in seeking out new partnerships with companies and organizations. In January, it announced agreements with ESA and the German space agency DLR to study technologies that could be incorporated into Dream Chaser, and even look at launching the vehicle on an Ariane 5 (see “Commercial crew’s critical year”, The Space Review, January 27, 2014). Last week, the company announced an agreement with the Houston Airport System to being studying what it would take to use Ellington Airport, a facility not far from NASA’s Johnson Space Center that airport managers are seeking to turn into a spaceport, as an alternative landing site for Dream Chaser.

SpaceX, perhaps the most visible of the three commercial crew contenders, is also approaching the end of its CCiCap award. “We have just four milestones left, only four, but they’re big ones,” said Garrett Reisman, DragonRider program manager for SpaceX, at Space Tech Expo. Two of those remaining milestones are technical reviews, including an integrated critical design review planned for next month.

The other two, though, are hardware flight tests of the Dragon’s launch escape system. “Those are the two big E-ticket items that are going to be super exciting,” he said. The first, planned for this summer, is a pad abort test, where a Dragon lifts off the pad at Cape Canaveral using its thrusters. The second, planned for later this year, will be an in-flight abort test where a Falcon 9 lifts off from Vandenberg Air Force Base and the Dragon separates around the time of maximum aerodynamic pressure on the vehicle.

Those tests, he said, will be among the final major tests needed before the crewed version of Dragon will be ready. “When we get that done, we’re pretty close to being there,” he said. “NASA has a goal of having certification complete in 2017, and we definitely intend to meet that goal.”

Getting the program funded

While Boeing, Sierra Nevada, and SpaceX all work to complete their CCiCap awards this year, they’re also playing a waiting game on the next phase, CCtCap. The companies submitted proposals in January for contracts that would cover development of spacecraft and initial test flights to the station, although awards are not expected from NASA until August.

| “This committee, this Congress, chose to rely on the Russians because they chose not to accept the President’s recommendation and request for full funding for commercial crew. You can’t have it both ways,” Bolden told a House committee. |

What’s not clear, though, is how many contracts NASA will award. (Unlike previous phases, done under more flexible funded Space Act Agreements, the CCtCap program will use conventional contracts under Federal Acquisition Regulations.) While NASA officials, including administrator Charles Bolden, have emphasized the desire of the agency to maintain competition, it’s unlikely given the program’s funding profile that all three companies can win contracts. The question will be whether NASA can afford two fully-funded contracts, or instead award “one and a half” contracts—a full-sized contract to one company and a smaller contract to a second company to allow them to continue work, but at a slower pace.

Bolden and others have offered few details about those awards, citing the “blackout” during the ongoing CCtCap procurement. Bolden, testifying before the Commerce, Justice, and Science (CJS) subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee on April 8, said the selections would be based in part on how much funding is available. Although the final fiscal year 2015 appropriations bills won't be done by the time of contract awards, Bolden said they hope to have a good idea by August of what they can expect based on the draft House and Senate versions of that bill.

“Just to be very candid, generally the House number [for commercial crew] is a little bit lower than the Senate number,” Bolden said at the hearing, “so if I get a good number from the House, no matter what it is, then we will take a look at that number, added to what we have for 2014, and that will help us determine how many we can select, whether it’s one, or one and a half, or two, or whatever.”

Since the rollout of NASA’s fiscal year 2015 budget proposal in early March—which coincided with the heightening of the Ukraine crisis—NASA has been emphasizing the importance for fully funding commercial crew in order to keep the program on track for 2017. Most of NASA’s statement on its ban of non-ISS cooperation with the Russian government, issued late April 2, actually dealt with commercial crew.

“This has been a top priority of the Obama Administration’s for the past five years, and had our plan been fully funded, we would have returned American human spaceflight launches – and the jobs they support – back to the United States next year,” the NASA statement read. “With the reduced level of funding approved by Congress, we’re now looking at launching from U.S. soil in 2017. The choice here is between fully funding the plan to bring space launches back to America or continuing to send millions of dollars to the Russians. It’s that simple.”

That message—funding commercial crew to end reliance on Russia—hasn’t yet resonated with many members of Congress. At last week’s appropriations hearing, as well as a March 27 hearing by the House Science Committee’s space subcommittee, members continued to express skepticism about whether commercial crew really needed the $848 million requested for 2015.

This led to some contentious moments in those hearings between members and NASA administrator Bolden. At the March hearing, Rep. Steven Palazzo (R-MS), chairman of the space subcommittee, questioned how critical full funding was given that NASA had been sticking to a 2017 date for some time despite not getting as much funding as requested. Bolden noted that the commercial crew program originally had a goal of 2015 for beginning such flights. “We would now find ourselves months away from launching Americans from American soil, and I would not have to worry about paying the Russians another $450 million,” had the program been fully funded from the outset, he argued. “If we don’t get what the President requested, I can’t guarantee 2017, I can’t guarantee competition, and we will continue to pay the Russians.”

Bolden argued that the slip in schedule from 2015, as originally proposed for the program when it was introduced in 2010, to 2017 was the fault of Congress. “This committee, this Congress, chose to rely on the Russians because they chose not to accept the President’s recommendation and request for full funding for commercial crew. You can’t have it both ways.”

Bolden had an even sharper argument last week with Rep. Frank Wolf (R-VA), chairman of CJS appropriations subcommittee, over funding for the program. After Bolden again argued that full funding was needed to avoid further slips, Wolf countered that Congress had, in fact, provided the program with plenty of funding. “Congress has provided a lot of funding for commercial crew, particularly once you take into account the larger fiscal situation. There’s never been a year that it was zero,” he said. “The appropriation has been at or above the authorized level in all the years but one.”

“I’m not sure where the [committee] staff says that you’ve given us more than we’ve asked. That’s just inaccurate.” Bolden responded, who appeared to take Wolf’s criticism personally. “Every time I come here, my integrity is impugned,” he said. “I am tired of having my integrity impugned by members of the committee and the staff.”

The dispute between Bolden and Wolf appeared to be rooted in a misunderstanding. Wolf was referring to levels authorized for commercial crew funding in the 2010 NASA authorization act: $312 million for fiscal year 2011, and $500 million each in fiscal years 2012 and 2013. Those amounts are close to what was actually appropriated: $307 million in 2011, $406 million in 2012, and $525 million in 2013. However, those figures were significantly below the administration’s original request, which in recent years have been in excess of $800 million, which Bolden argued led to the delays in the program from 2015 to 2017.

Later in the appropriations hearing, Bolden was more conciliatory. “Mr. Chairman, I apologize for losing my temper,” he said to Wolf. “I get hot sometimes and I think I misunderstood you.”

| Given the congressional track record of funding past budget requests for the program, NASA shouldn’t count on getting the $848 million it requested for the program, which will, in turn, have implications for how many of the three companies currently in the program will proceed to the next phase. |

While NASA has used the current crisis to press for commercial crew funding, the agency has acknowledged it’s not a near-term solution should Russia cut off NASA’s access to Soyuz spacecraft in the near future. Bolden called commercial crew the backup to Soyuz at the Science Committee hearing, but said it was a three-year backup. That’s the same, he argued, as the Air Force’s backup plans should Russia cut off access to the RD-180 engine used by the Atlas V first stage: it is studying domestic production, but acknowledges it would take as long as five years to develop a domestic RD-180 production line.

Some in the space community have argued that, in an emergency, the existing cargo version of the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft could be pressed into service to carry crews. However, asked about this at Space Tech Expo, SpaceX’s Reisman argued that while Dragon was designed from the outset to carry people, it would not be that simple to quickly convert the cargo version to carry people.

“There are significant upgrades that would need to be made before you could even entertain the idea of putting crew on there,” he said. Besides no launch escape system on the cargo version of Dragon, he said, there’s no life support system capable of supporting crews, and no displays or controls in the spacecraft for those crews. “I think the way we’re heading, and meeting all of the NASA requirements, is the right thing to do to have a vehicle we’re going to strap people into.”

This all suggests that Congress’s decision on funding for commercial crew will be largely decoupled from the current state of US-Russian relations, despite the best efforts of NASA to play up the program as an alternative to reliance on Russia’s Soyuz. Given the congressional track record of funding past budget requests for the program, NASA shouldn’t count on getting the $848 million it requested for the program, which will, in turn, have implications for how many of the three companies currently in the program will proceed to the next phase.