Remembrances of conferences pastby Jeff Foust

|

| The year 1985 was an interesting one, the beginning of a transition that perhaps few at that time realized. |

The ISDC is one of the longer-running space conferences of any kind in existence today: this year’s event is the 33rd annual ISDC. The conference itself even predates the NSS, having been started by the L5 Society several years before its merger with the National Space Institute created the modern-day NSS. A lot has also changed in the space industry itself since the conferences started in the early 1980s.

I stumbled across a measure of that earlier this year at another conference, the American Astronautical Society’s (AAS’s) Goddard Memorial Symposium outside Washington. The conference had a table of free books, primarily extra copies of publications by the organization from years ago. Free books are usually free for a reason, but one title caught my eye: Proceedings of the Fourth Annual L5 Space Development Conference. It was a time capsule of sorts to the early years of the conference, and a different era in space commerce and advocacy.

The 4th annual L5 Space Development Conference (it would not become the ISDC for a few years, even though the conference has always been held in the US other than 1994, in Toronto) took place in Washington on April 25–28, 1985. As the name suggests, this conference was an L5 Society event, but held in cooperation with the National Space Institute, AAS, Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS), and other organizations. The book is a transcript of many of the conference sessions, although not a complete record: a few sessions were not recorded, and there are gaps in a few others. Nonetheless, it offers a look back into both the visions and concerns of an earlier era.

The year 1985 was an interesting one, the beginning of a transition that perhaps few at that time realized. By 1985 it was increasingly clear that the Space Shuttle would not realize the flight rates and low launch prices originally envisioned for it a decade earlier. Yet, the shuttle’s flight rate was ramping up, something that was expected to continue for the next several years; the path to space development, for all intents and purposes at the time, was through enhanced use the shuttle. The Space Station program was still in its early phases, but already under political attack: the proceedings include several references for calls to action by participants, asking them to contact members of Congress to keep the program funded.

At the same time, a new effort to craft a future of space was underway. The previous October, President Ronald Reagan established the National Commission on Space, a group charged with developing a long-term plan for the nation’s space program. “We owe it to the President of the United States to create a vision to space and America in the next 25 years,” said David Webb, one of the commissioners, in the conference’s welcoming address. He credited the space community for his participation on the commission. “For the very first time in the history of the space movement, this constituency has been recognized seriously.”

Another commissioner with even deeper roots in the space movement was Gerard K. O’Neill, who gave a keynote address at the 1985 conference. He mentioned his participation after discussing some familiar topics for him, from the utilization of space resources to the development of space colonies. He promised, though, to go into the commission with an open mind about what the nation’s future in space should be. “Like my colleagues on the Commission I will wipe that slate clean, and become a sponge for the absorption of ideas form you and other people over the next six months or so,” he said, referring to the fact-finding phase of the commission’s work.

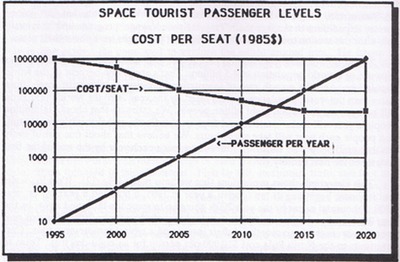

| Citron projected truly exponential growth for the industry, with the number of customers growing by an order of magnitude every five years: from 10 per year in 1995 to one million per year by 2020. |

Those plans, though, were disrupted just nine months after the conference with the loss of the Space Shuttle Challenger. Its loss put to rest once and for all the belief that the shuttle could make spaceflight more routine and less expensive, which would thus enable new applications. The National Commission on Space completed its work and issued its report, but its vision for American spaceflight for the next half-century was largely ignored, overshadowed by the investigation into the Challenger accident.

Besides the near-term disruptions to those long-term visions, the nearly three decades since the conference allow the reader to examine how some of the speakers’ long-term projects panned out. And, usually, they didn’t. In one session, Milton Copolus of the Heritage Foundation projected that, by the year 2000, space commerce would generate $200 billion a year, increasing to about $500 billion a year by 2010 (about $440 billion and $1.1 trillion in 2014 dollars.) By comparison, the Space Foundation reported last year that the total value of the “global space economy”—which includes government and commercial spending—in 2012 was just over $300 billion. (The Satellite Industry Association’s annual report, which focuses only on commercial revenues, counted $189.5 billion in revenues in 2012.) And that, perhaps, was one of the better predictions.

In a panel on space tourism at the conference, Bob Citron, one of the pioneers of space commercialization, projected truly exponential growth for the industry, with the number of customers growing by an order of magnitude every five years: from 10 per year in 1995 to one million per year by 2020. Prices would drop sharply as well. “We believe that within the next fifteen to twenty years a three-day Earth-orbit space tour might cost $25,000 to $50,000 per person in 1985 dollars,” he said.

Reality has worked out a little differently. We are not flying tens of thousands of tourists—or anyone else—into space each year, as Citron’s projections stated; the cumulative number of space tourists, who paid for trips into orbit on Soyuz missions to the International Space Station, remains in the single digits. No one is proposing orbital trips for $55,000–110,000 a person (Citron’s 1985 prices in current-day dollars) any time in the foreseeable future. Those prices are, in fact, at the low end of suborbital space tourism ticket prices today: XCOR charges nearly $100,000 a seat, while Virgin Galactic’s prices rose last year to $250,000.

A figure from Bob Citron’s presentation about space tourism in 1985, projecting exponential growth in space tourism (note the y-axis is in log format). Had his predictions come true, there would be nearly 100,000 people flying to orbit this year, at ticket prices less than current pricing for suborbital space tourism flights. |

Citron’s optimism was based on use of the Space Shuttle to support tourism, showing off designs of modules that could fit into the shuttle’s cargo bay and accommodate as many as 74 people. The problem, he identified, was that this would, at projected shuttle launch costs, bring the ticket price down to “only” $1.5 million in 1985 dollars. In retrospect, that would be a bargain even at the inflated 2014 price of $3.3 million, given that Space Adventures currently charges more than $50 million for a Soyuz seat on those rare occasions when an additional seat is available.

To lower prices further, Citron suggested combining passenger flights with launches of satellites or other cargo. Or, he added, NASA could help subsidize the industry. “Maybe NASA would consider a space tourism joint-endeavor agreement that would, for the benefit of space tourism development, provide a series of free shuttle flights to the private company that raises the $250 million required to finance the development of a space shuttle passenger cabin and establish an effective international space tourism marketing organization,” he said.

| Certainly one major reason for the lack of progress in so many commercial space ventures since 1985 is the high cost of space transportation. |

Citron’s proposal, at first glance, looks outlandish: free shuttle flights for launching tourists? Yet, the overall approach—a public-private partnership—is not so far off from what NASA is doing today in supporting the development of commercial crew transportation systems. Instead of providing shuttle flights that would cost hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars, NASA is instead providing several billion dollars, plus the promise of a market in ferrying astronauts to and from the station, while requiring the companies to make significant investments of their own and use those vehicles for other markets, including space tourism. Citron’s market forecasts may have been way off, but he may have been quite prescient in forecasting how commercial orbital human spaceflight could develop in partnership with NASA.

Similarly, in his keynote, O’Neill offered a vision of the future that came to pass, just not as he expected it. Before diving into the familiar optics of lunar resources and space colonies, he discussed his work creating a new company, Geostar Corporation, that planned to use satellite in geostationary orbit to provide both communications and navigation services. As he described it, a Geostar user would, for $20–45 per month (in 1985 dollars), get accurate positioning information and even turn-by-turn navigation, as well as be able to send short “telegraphic messages” anywhere in the continental US.

Today, of course, we have those services and much more in the form of smartphones, which can give us our position, provide directions, and text (or email, or tweet, or more) people. Virtually none of those services, though, are provided by commercial satellites: terrestrial wireless networks long ago dominated over satellites systems in GEO or low Earth orbits, and the government’s decision to make the GPS system free for civilian use undermined any business case for a commercial satellite navigation system.

At the 1985 conference, though, O’Neill believed enough in Geostar—which he saw as a way to help finance future space development efforts, making his Space Studies Institute the largest shareholder—to step down from his faculty position at Princeton. At the conference, he said he has been recently notified by the university that he was now a “Professor Emeritus.” “Somehow that gives me the feeling that I should be doddering about on a cane,” he said, “but I hope that there are a few good years left in me.”

Sadly, there were only a few good years left: he died of leukemia in 1992. Geostar went bankrupt around the same time, its assets later acquired in part by commercial communications satellite company Iridium.

That should, perhaps, serve as a cautionary tale for those attending this year’s ISDC, who may hear enthusiastic pitches about the prospects of space development, including topics like space solar power, asteroid mining, and space tourism, that were also presented at 1985’s conference. Has so little changed in the last three decades?

Well, maybe. Certainly one major reason for the lack of progress in so many commercial space ventures is the high cost of space transportation. Few space-based commercial services can compete with terrestrial alternatives on a cost basis, with communications and, to a lesser extent, remote sensing being the exceptions. (While navigation services is a large and growing market, the space-based systems that provide them are funded and operated by governments.) Space manufacturing, resource extraction, and energy don’t provide enough unique benefits to make up for their far higher prices than terrestrial services. Even space tourism must complete with terrestrial adventure and luxury travel options.

The good news is that the cost of transportation is going down. In his 1985 keynote, O’Neill quoted a price per pound for geostationary satellites of $10,000, which works out to almost $50,000 per kilogram in today’s dollars. Today, though, a large communications satellite can be launched to GEO for significantly less than half that price, depending on the specifics of any given launch deal. However, that price decline hasn’t triggered a significant increase in demand, either for commercial communications satellites or other applications.

| “The next year is going to show whether or not the space movement can rise to this challenge and whether, in fact, we have at last come of age,” Webb said in his opening remarks at the 1985 conference. |

Further price declines, though, are on the horizon. SpaceX is already offering Falcon 9 launches for about $60 million each—about $12,000 per kilogram given its current GEO capacity. The Falcon Heavy will, if it meets SpaceX’s price and performance targets, reduce that price-per-kilogram by about half. SpaceX is also pursuing reusability of the Falcon 9 that could further reduce prices. Will that—or efforts by other companies, like Blue Origin—be enough to enable some of these new markets? Hopefully it won’t take three decades to find out, one way or the other.

And what of space advocacy in general? The 1985 conference billed that year as a make-or-break moment for a relatively fractured movement. “The next year is going to show whether or not the space movement can rise to this challenge and whether, in fact, we have at last come of age,” Webb said in his opening remarks, referring to the need to stand up with a single voice as his commission examined the space program’s future.

That year may have neither made nor broke the “space movement” (a term that, in many respects, sounds quaint today), which has instead muddled though the last few decades. While some organizations have continued on to the present day, others have faded away, like one of the conference co-sponsors, the American Space Foundation. (In the book’s preface, the ASF is described as “organizing public support for increasing NASA’s budget to 1% of federal spending,” a reminder that contemporary calls for a “penny for NASA” are neither new nor necessarily effective.) Getting space organizations to “stand up and be counted with one voice,” as Webb requested, may be no easier today.

However, the NSS, and the ISDC, endures. Today the NSS doesn’t produce similar printed or electronic proceedings of its conferences, but many sessions are recorded on video. Perhaps, in the early 2040s, someone will look back on videos from the 2014 ISDC and analyze what the speakers got right and wrong—hopefully, she or he will be doing so from Earth orbit or beyond.