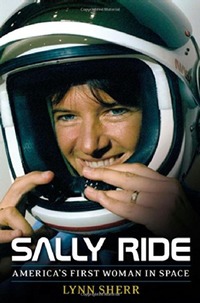

Review: Sally Rideby Jeff Foust

|

| “I read through the list of requirements for mission specialist and said to myself, ‘I could do that,’” Ride later recalled when she saw NASA was recruiting female astronauts. |

But Ride also had her secrets, kept hidden from even people like Sherr, who considered herself close friends with Ride. One of them was the cancer that would take her life nearly two years ago at the age of 61. Another was her long partnership with Tam O’Shaughnessy, publicly revealed only in her official obituary. “Sally was very good at keeping secrets,” Sherr writes in the introduction of this book, which offers the fullest picture yet—and, perhaps, the fullest picture ever—of a woman many people only thought they knew.

Ride was, as Sherr describes, a quintessential “California girl,” born and raised in southern California, and far more comfortable in her adult life living in the Golden State than in Houston or Washington. While she had some success as a tennis player through high school and into college, her real passion was for science, particularly astrophysics. It was not, though, until NASA put out its call for female astronaut applicants as she was finishing up her PhD at Stanford University that she envisioned herself becoming an astronaut. “I read through the list of requirements for mission specialist and said to myself, ‘I could do that,’” she later recalled, as noted in the book. (A 1969 newspaper article from Ride’s brief time as a student at Swarthmore College predicted that Ride “may one day be the first woman astronaut” but Ride “had no recollection of mentioning any NASA goals to the reporter,” Sherr writes.)

Ride entered the public spotlight as one of the 35 members of the astronaut class of 1978 (the “Thirty-Five New Guys,” or TFNG, an acronym with an alternative, and more off-color, expansion), and one of six female members of that class. One of those six would be the first American woman in space, but how did Ride win that historic nod? Robert Crippen, the astronaut who commanded STS-7, says in the book that it was in large part due to Ride’s proficiency with the shuttle’s robotic arm, which would be used extensively on the mission. “She was clearly the best RMS [remote manipulator system] operator we had,” added George Abbey, the Johnson Space Center official with tremendous influence in the selection of shuttle crews.

Sherr, in the book and in interviews, puts much of the credit for that selection on Ride’s experience in tennis, beyond the hand-eye coordination she developed as a player that helped with operating the robotic arm. “It really helped her when she got to NASA,” Sherr said of that background in an on-stage interview at the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington last week, aired on NASA TV. “NASA doesn’t want individual stars. NASA wants team players. And Sally, having worked in the tennis business, could be a team player.”

Outwardly, Ride, ever the team player, handled the media and public attention that came before, during, and after the mission with aplomb. But, as Sherr described in the book, that media attention took a toll on Ride, who was very much an introvert. “I think she was kind of traumatized by all of the public attention she had to go through,” recalled a close friend, Susan Okie. Sherr cites the “psychic price” Ride paid for being the first woman in space as one of the secrets she kept hidden even from close friends, along with Ride’s cancer and her relationship with O’Shaughnessy.

| “She believed, rightly, that knowing the truth would make NASA a better place,” Sherr said of Ride. “She didn’t want to punish NASA, she wanted it to get better.” |

Those other secrets get covered in the book as well. The book’s penultimate chapter traces Ride’s battle with pancreatic cancer from the spring of 2011 through her death in July 2012, a battle she shared with only her innermost circle. Sherr also traces Ride’s relationships with both women and men through her life, including her marriage to fellow astronaut Steve Hawley and her partnership with O’Shaughnessy, a woman the public knew prior to Ride’s death only as her business partner in their education company, Sally Ride Science. Examining any individual’s history of romantic relationships runs the risk of salaciousness, but Sherr navigates that history expertly, with the cooperation of many of those involved.

Ride also had her secrets about space. She was the only person to serve on the commissions that investigated the loss of Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003, and both times was a surreptitious conduit of information. On the Rogers Commission in 1986, she received information about the deteriorating performance of the solid rocket boosters’ O-rings in cold temperatures from a source within NASA. Knowing that sharing that information could get that source—still a mystery, even to Ride’s biographer—fired, she quietly shared the information with a fellow commissioner, Don Kutnya, who “figured out a way to plant the concept” with yet another member of the commission, Nobel laureate physicist Richard Feynman. It was Feynman, of course, who publicly illustrated the O-rings’ lack of resiliency at cold temperatures during a public hearing, allowing Ride to get that information public without implicating her source—or herself, for that matter. (Ride’s role was only revealed by Kutnya after her death, and was also mentioned in the 2013 film The Challenger Disaster that starred William Hurt as Feynman.)

Ride played a similar, although more direct, role as a conduit for information as a member of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB) in 2003. The CAIB had found that, if the damage to the orbiter had been known early enough, it might have been possible to rescue the crew, contrary to NASA’s public claims that there was nothing they could have done. They were worried, through, Sherr writes, “that NASA management might get wind of it and try to discredit their findings.” So Ride leaked the findings to a reporter, Todd Halvorson of Florida Today (with whom Ride had worked during her relatively brief stint as president of SPACE.com several years earlier) prior to CAIB’s briefing on the report, ensuring the word got out before NASA could put any spin on it.

Those leaks, Sherr said in her NASM interview last week, were not acts of disloyalty to NASA but just the opposite. “She believed, rightly, that knowing the truth would make NASA a better place,” she said. “She didn’t want to punish NASA, she wanted it to get better… She had once been the bright new face of NASA, and now she became NASA’s conscience.”

| “There was, in my mind, constant tension between ‘am I reporter, or am I a friend?’” Sherr said. “I didn’t pull any punches. Everything that I found out is in there.” |

In Sally Ride, Sherr walks a fine line. On one hand, she considered herself a close friend of Ride’s, knowing her for 30 years. On the other, she is a journalist and a biographer tasked with describing Ride’s life as completely as possible, at the request and with the support of Ride’s family. “So yes, I bring bias to this project, but I have not checked my journalism credentials at the door,” Sherr writes in the book’s introduction.

“There was, in my mind, constant tension between ‘am I reporter, or am I a friend?’” Sherr acknowledged in her NASM interview, one that she said tipped in favor of being a reporter. “I didn’t pull any punches. Everything that I found out is in there.”

It’s hard to quibble with that approach, which has resulted in the best, most three-dimensional portrait yet of one of the most famous astronauts in American history. It might be the most complete biography ever of Ride: while her papers have been donated to the Smithsonian, she did not keep extensive written records of her life; the book also benefits from the cooperation of Ride’s family and interviews with an extensive number of Ride’s contemporaries that wouldn’t be possible decades hence. Sally Ride may offer the best review possible of her three lives: public, private, and secret—at least, for that last category, those secrets she was willing to share with someone.