Spinning to Marsby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Today, it is difficult to remember that after an initial flurry of activity in the 1960s and 1970s, Mars was ignored by the world’s space powers for a very long time. |

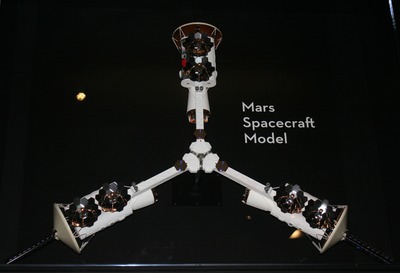

Thirty years ago today a group of scientists, grad students, and all around Mars enthusiasts wrapped up the four-day Case for Mars conference in Boulder, Colorado. While there, they drafted plans for a human Mars spacecraft that became enshrined—at least for a little while—in popular culture. A large spinning vessel consisting of three nearly identical ships and their landing craft, it was a serious attempt at defining a human mission to Mars. By the early 1990s, one of the Case for Mars participants, Carter Emmart, produced a beautifully detailed model of the spinning spacecraft that was placed on display in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. Now, after a long absence, that model is back in public view.

The long dark nothingness…

Today, with two rovers on Mars, a third being built, three spacecraft orbiting the Red Planet, and two more heading there, it is difficult to remember that after an initial flurry of activity in the 1960s and 1970s, Mars was ignored by the world’s space powers for a very long time. NASA’s two Viking missions, which landed on Mars in 1976, were incredibly expensive. It was partly this expense, as well as their failure to find life on the Martian surface—that many believed was their raison d'être—that led to no further American Mars missions for seventeen years. Throughout the 1980s there were only two missions launched to Mars, the Soviet Phobos spacecraft, one of which failed on its way to the planet and the other failing only a couple of months after entering orbit. Mars remained an interesting scientific target, as well as an enticing goal for human spaceflight, and there was no shortage of proposed Mars science missions in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But none were approved for development. The powers that be did not want to hear about Mars missions, let alone fund any of them.

This lack of attention prompted a group of graduate students at the University of Boulder, Colorado, to hold the first Case for Mars conference in 1981. Their objective was, as the conference name indicated, to make a case for Mars, both for further robotic science spacecraft and human missions. In 1984 they did it again, holding a bigger conference with a broader perspective. The Case for Mars II conference was sponsored by The Planetary Society, with the University of Colorado Space Interest Group organizing the panel discussions and mission planning workshops. Carter Emmart was one of the founders of the group and one of the six original founders of the Case for Mars.

Although the Jet Propulsion Laboratory had been proposing robotic Mars spacecraft after Viking, including rovers, airplanes, and various orbiters, there had not been any detailed proposals for human Mars spacecraft during this time. In the latter 1960s, NASA had studied human Mars spacecraft using nuclear propulsion, and that concept had received a lot of publicity. The spacecraft design appeared in artwork and several works of fiction, such as Gordon Dickson’s 1973 novel The Far Call and Stephen Baxter’s 1997 book Voyage. Amusingly, the 45-year-old spacecraft design has recently appeared on the cover of Rod Pyle’s management book Innovation the NASA Way. (See “Review: Innovation the NASA Way”, The Space Review, May 27, 2014). But throughout the 1970s, nobody was seriously evaluating human Mars missions, certainly not NASA, which had its hands full developing the Space Shuttle.

As the Space Shuttle began operating and the European Space Agency was developing the Spacelab module, people began considering whether systems and equipment developed for use in the shuttle’s payload bay could be adapted for long-duration missions to Mars. There were several proposals for such spacecraft, usually made by individuals, not NASA spacecraft designers.

The University of Colorado Space Interest Group put on their first Case for Mars conference arguing that it was time to resume robotic exploration of Mars, and that Mars was also an exciting destination for human missions. By the time of their second conference they had become more ambitious and added the goal of designing a baseline human Mars mission. This became what they called their “conceptual point mission design.”

| For a decade Emmart’s spacecraft slowly spun inside the exhibit, undoubtedly mesmerizing some of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who walked past it. |

Many human Mars mission designs start with a simple no-frills first mission with one of the top objectives being keeping the cost down. The Case for Mars II workshop participants had different objectives, including establishing a 15-person permanent initial base that would expand every two years. In order to reduce the cost of this more ambitious goal, their design relied heavily upon a set of three reusable spacecraft that would carry multiple crews to Mars, shuttling back and forth from Earth orbit to a Mars flyby, landing their crews in aerocapture vehicles. The crew landers would detach from the habitats before reaching Mars and then aerocapture down to the surface as the now uninhabited ferry spacecraft headed back to Earth. The crews would stay on Mars for at least two years, awaiting the next habitat flyby. Their ascent spacecraft would use propellant manufactured from the Martian atmosphere. The “interplanetary spacecraft” would include habitation modules based upon systems then under consideration for the planned Space Station Freedom.

The workshop participants determined that some kind of microgravity environment was necessary for the trip, so they settled upon providing the equivalent of Mars gravity—38% of Earth gravity—on the spacecraft during transit. The three Mars spacecraft would boost out of Earth orbit and then link up and begin rotating. Assuming that they would achieve Mars gravity near their outermost decks, this would require a relatively high spin rate over three rotations per minute.

Designing a human deep space exploration mission is a huge undertaking, requiring analysis of everything from trajectories to engineering design to consumables and supplies to human factors. There was no way that a workshop lasting less than a week could do anything more than take a rudimentary initial first cut at it. But the workshop also included two artists: Mike Carroll and Carter Emmart. Emmart produced a series of quick sketches of the human Mars mission and Carroll later produced paintings. Their work appeared in the conference proceedings published by the American Astronomical Society Press in 1985 and edited by Chris McKay, who later became a noted space scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory later produced a more than 100-page report on the human Mars mission.

Carter Emmart illustrated the Mars spacecraft design developed during the Case for Mars II conference. (credit: C. Emmart) |

Emmart soon refined his sketches into a series of pencil drawings showing all the major steps of the mission. Both men’s artwork began appearing in various venues and because of this they started to influence even broader audiences. The Mars spinner spacecraft appeared in Allen Steele’s 1992 novel Labyrinth of Night, as well as Ian Douglas’ 1998 novel Semper Mars.

In December 1992 the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum opened an exhibit titled “Where Next Columbus?” that examined “the motives and methods of past and present exploration, as well as the options and possibilities for future space exploration.” It also discussed the “scientific, economic, ethical, and political challenges” of future human space exploration. The section of the exhibit Exploring New Worlds in Space featured a model of the Mars spacecraft that Emmart constructed. With a diameter of nearly two meters, it was mounted in a display case and slowly rotated. Museum visitors who peered closely at the cutaway section of one of the habitation modules could see an astronaut taking a shower. And if they looked really closely, they could also see the small “Terminator” movie poster that Emmart had placed in one of the living quarters.

For a decade Emmart’s spacecraft slowly spun inside the exhibit, undoubtedly mesmerizing some of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who walked past it, and sparking youngsters to imagine themselves inside such a spacecraft on a journey to Mars. The exhibit closed in March 2002 and Emmart’s model went into storage.

Recently the model was removed from its crate and placed on display in the museum’s “Moving Beyond Earth” exhibit; a permanent exhibit that does rotate some of the items on display. Emmart’s Mars spinner is not literally rotating in its display case, which is unfortunately not mounted at eye level but above a large Earth terrain simulator.

| In 1984 some dreamers dreamt of humans on Mars, and probably thought that it would happen by the futuristic date of 2014. But could they have envisioned a global communications network that connected computers in Washington, DC and people on trains in Thailand? |

Throughout the eighties the group of Mars enthusiasts that started the Case for Mars conferences graduated, got jobs, had families, moved away from Boulder, and did all the things that people do as they get older. As a result, the Case for Mars conferences lost steam. But by the early 1990s Robert Zubrin was aggressively pitching his “Mars Direct” approach to Mars which he claimed was capable of achieving a first landing on Mars much faster and less expensively than previous proposals. Zubrin appropriated the Case for Mars term and eventually created The Mars Society, which had a much more antagonistic attitude toward NASA than the Colorado Space Interest Group.

Thirty years ago, a group of Mars enthusiasts dreamt of a human future on Mars. But just the other day I took a digital photo of Emmart’s Mars spacecraft and via Leonard David, one of the original Case for Mars dreamers, emailed it to Emmart. The electronic communication with its digital image transited the globe via fiber optic cable and possibly even satellite, and as chance would have it, reached Emmart, who was at that moment on a train traveling from Udorn Thani to Bangkok, having just viewed a planetarium show he produced, which was projected on a dome… in Beijing. In 1984 some dreamers dreamt of humans on Mars, and probably thought that it would happen by the futuristic date of 2014. But could they have envisioned a global communications network that connected computers in Washington, DC and people on trains in Thailand? Could they have envisioned a world in which the Soviet Union no longer existed, or where American movies and planetarium shows were projected in Chinese mega-cities?

The Future, it is here. It just isn’t currently on Mars.