Review: No Requiem for the Space Ageby Jeff Foust

|

| “NASA may have been harmless—at worst, unnecessary and unrewarding—but it had the bad fortune to promote itself as the next logical step in national and human progress at a moment when the very meaning of ‘progress’ was engulfed in controversy.” |

The history of human space exploration since Apollo has been one of fits and starts, initiatives often boldly announced only to quietly fade away. Over time, even staunch space advocates have come to recognize that Apollo was not the beginning of a broader expansion into the solar system but instead an aberration fueled by the Cold War competition—the Space Race—with the Soviet Union. When the US “won” that race, the incentive to continue the program went away. And even during the height of the Apollo program, public support for the program was nowhere near as high as our nostalgia-tainted recollections claim.

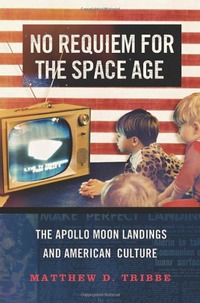

However, the failure to build upon Apollo may have an even more fundamental cause than a Cold War competition. In No Requiem for the Space Age, historian Matthew Tribbe argues that Apollo took place just as American society was undergoing a transition from “rationalism” to “neo-romanticism.” The former represented the philosophy predominant in America after World War II, where science and technology played a key role in advancing society. The latter was the reaction to it that emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s in forms like the counterculture movement and rise in interest in mysticism.

What does that have to do with sending humans to the Moon? Tribbe sees Apollo as the apex of rationalism, a massive harnessing of technology to achieve a goal. By the time NASA achieved that goal, though, rationalism was giving ground to neo-romanticism, as many Americans became skeptical of the benefits technology offered. “NASA may have been harmless—at worst, unnecessary and unrewarding—but it had the bad fortune to promote itself as the next logical step in national and human progress at a moment when the very meaning of ‘progress’ was engulfed in controversy,” he writes.

| “Ultimately, Americans were unable to successfully invest it with any deeper meaning than simply being an amazing human accomplishment.” |

Tribbe makes his case in several ways. One is to note the limited effect the Apollo 11 mission had on society. The first landing on the Moon may have been a major historical milestone, but commentators even then struggled to explain its significance. (Tribbe devotes a chapter to Norman Mailer’s struggles to write about Apollo, which led to the critically underwhelming book Of a Fire on the Moon.) A year after Apollo 11, newspapers found that a majority of Americans—14 of 15 in St. Louis, in an informal New York Times poll—could not recall the name of the first man to set foot on the Moon. Meanwhile, he recounts, the rise of neo-romanticism, critical of the role of science and technology played in society’s ills at the time, challenged the benefits of such ventures.

While space exploration didn’t threaten society in the same way as technology did elsewhere, in the form or war or environmental degradation, Apollo did commit, in the eyes of many, the sin of “demystifying” the Moon, turning into a bland, gray world. “This disenchantment helped reveal the spiritual poverty of ventures like Apollo, and can help explain why it turned out to be so dissatisfying to so many,” Tribbe writes. “Ultimately, Americans were unable to successfully invest it with any deeper meaning than simply being an amazing human accomplishment.”

And without that deeper meaning, there was little desire to try and follow up Apollo, Tribbe concludes. Neo-romanticism didn’t supplant rationalism in the end, he concludes, as the two philosophies have learned to coexist: today we embrace the advancement of technology, but also spiritualism as well. That reconciliation, though, appears to have done nothing to advance the cause of human space exploration, in at least anything like the Apollo paradigm that sent humans to the Moon 45 years ago, but has failed to return them for more than 40 years.