New Fort Knox: A means to a solar-system-wide economyby Richard Godwin

|

| The problem is connecting the dots from an economic viewpoint so that the business case can close and sustainably allows the endeavor to continue. In other words, our community doesn’t talk the language of investment bankers. |

The biggest hurdle isn’t the engineering. It’s not that we don’t dream big enough and it has little to do with national government. Rather, it’s that we simply cannot comprehend the economics. Let’s put it another way: we will not achieve this until we convince the investment community that there is that substantial return on investment (ROI) that they require.

Any economic zone of influence needs trade, finance, banking, manufacturing, consumption, and all basic needs that those processes encompass and rely upon: food, shelter, the ability to raise families, and, most importantly, the pursuit of happiness, which makes it all possible.

To hear the dreamers speak of mining asteroids or building power stations in space is to realize that we do indeed, as a species, dream big. The problem is connecting the dots from an economic viewpoint so that the business case can close and sustainably allows the endeavor to continue. In other words, our community doesn’t talk the language of investment bankers.

So, how do we get the investment community to commit the staggering sums required to mine an asteroid, to therefore transform a company with a dream and some fancy engineering into a profitable venture? Indeed, the answer is to convince them your engineering is sound, but mainly that your business can produce the ROI concomitant with the high risk involved.

Many spacers will argue that we have already identified certain asteroids containing enormous quantities of platinum group metals, waiting to be mined. For example the value for one candidate in the main belt has been pegged at $19 trillion. That’s a big number. However, it doesn’t close the business loop: if you drop that much platinum into Earth’s market, you will be selling it by the ton, not by the ounce. Its value as a precious metal will be subsumed by availability.

Some would state the answer is to adopt DeBeers business model: maintain the rarity by squeezing only relatively small amounts into the main economy. That’s a nice idea, but not one that will best serve your investors. Rationing small amounts will not finance a multi-billion-dollar enterprise.

Others would state that they would process the metals and sell them to the increasing number of new business ventures in low Earth orbit and beyond. In other words, “if we build it, they will come.” That’s a quaint but outdated 19th century business motto, and again not something that will convince your investors.

For an investor to view a new idea as a viable business, the company must ensure it has five crucial elements in place: a problem to solve, a solution to the problem, an end client for your solution, money (of course), and, finally, execution, execution, execution!

| Without ever having to return any platinum, palladium, or iridium to the surface of the Earth (except for public relations purposes), start printing your own bullion backed currency on Earth, where the real market resides—at least for now. |

The biggest problem for operating an economy that spans the solar system is having to deal with the laws of physics and the enormous distances involved. Trade cannot be run by large freighters running physical goods between planets. Trade, if anything, is going to be of an intellectual sort, with an open flow of ideas. But even this model will be tough. Elon Musk’s intrepid colonists to Mars will be little more than a high-tech hippie colony, with initially little specialization of skill sets. Those initial castaways will be producing water, food, shelter, and the energy needed for their basic needs. A large initial industry might be making bricks—hardly a high-tech tradable resource!

It will be required that these off world pioneers come to terms with physics, delta-V, and sustainable economics. How to marry these problems and find a solution?

An endeavor like settling a new planet will require equally bold economic thought and completely out-of-the-box financial creativity and ideas. What I propose is a staggered approach for a space corporation to become a sizable and highly profitable solar-system-wide entity.

First: Don’t go straight for the asteroid belt. Start closer and easier instead. Use the technology needed for asteroid mining to first start clearing space junk in Earth orbit. Governments will, sooner or later, be compelled to fix the mess they’ve created. At the moment, some propose to drop the large junk into the ocean, but that requires more delta-V than moving it into what you might call a “Sanford and Son” or “scrapyard” orbit. Moving junk into a scrap orbit could provide the first revenue stream for the company, with governments as first anchor client.

Second: The “junk” is mainly comprised of aerospace-grade aluminum and other metals, at a cost of about $20,000 per kilogram to place into orbit. This becomes a commercial second revenue stream for the company, selling to other new clients that will likely emerge. Chew up the junk into aluminum powder, place it in 3D printers, and sell finished products on orbit, whatever the client requires.

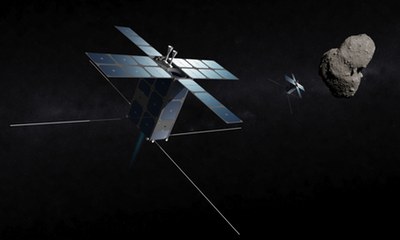

Third: Now it’s time for some innovative economic and financial thinking. You now have a revenue stream and enough expertise to go mine that platinum asteroid. Don’t even think of bringing an asteroid back to cislunar space, though: it’s too dangerous, or at least perceived as such. Process your platinum at the main belt location: two cubic feet (0.05 cubic meters) of platinum weighs approximately one ton of mass and is worth about $55 million at current market prices. Start returning the processed precious metals to a bullion repository in a strategic yet convenient location, such as the Earth-Moon L1 Lagrange point, where it will be visible from Earth. Call it New Fort Knox if you like. Now invite up a few key visitors to view your bullion repository: perhaps a delegate from World Bank, the Federal Reserve, Lloyds of London. Let them observe the ever-accreting mass of precious metal at your “vault” in the sky. Demonstrate to them the rate of increase of mass, and boast the security of your facility and the quality and purity of the metal.

At this point, without ever having to return any platinum, palladium, or iridium to the surface of the Earth (except for public relations purposes), you start printing your own bullion backed currency on Earth, where the real market resides—at least for now. The world is ripe for a better securitized default currency for closing all trade or commodity deals around the world. A currency backed by limitless precious resources, with more practical utility than gold, pay be preferable to currencies backed the good faith of governments perhaps incapable of balancing their own books.

The Federal Reserve, along with the US government, enjoys enormous benefit from being the world’s reserve currency. The US must look to this technology, which may perhaps provide a continued and advantaged position in perpetuity, to it and to the financial markets. If not, someone else will eventually figure out that the way to control a solar-system-wide economy is to maintain the resources securely off-world and use them to securitize a new currency; one that is accepted as backed by real value, as opposed to merely a promise. Printing the solar system’s default currency bestows upon the issuer a seat at the high table of global finance.