Review: Hubble’s Legacyby Jeff Foust

|

| “I have been so intimately involved with the HST for 30 years that when people talk about the separation of robotic and human, I kind of get bewildered,” Weiler writes. |

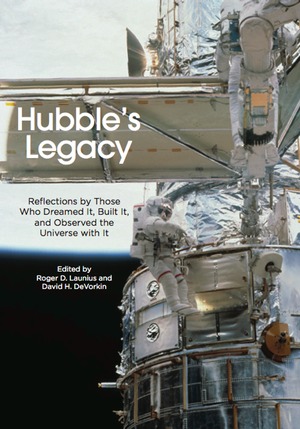

There are plenty of accounts of the history of Hubble, both from programmatic and scientific standpoints: how Hubble was built, and how it was used. Hubble’s Legacy does not pretend to be a comprehensive history of the space telescope, but instead snapshots of various aspects of the telescope’s development and operation, many from some of the key individuals involved in Hubble. They offer narrow, but deep, views, just like the images produced by Hubble. The essays, published in a free ebook by the Smithsonian Institution, came out of a symposium of the same name held at the National Air and Space Museum in 2009.

The book, like the 2009 symposium, covers Hubble’s history in three parts. The first is the development of Hubble itself, from the initial concept of a spaceborne telescope to the funding and development of Hubble as an observatory that could be repaired and upgraded by the Space Shuttle. The second part centers on the crisis that enveloped Hubble, and NASA, after the telescope’s launch and the efforts to develop instruments to restore the telescope’s eyesight. The third part looks at both Hubble’s scientific and cultural windfall since the telescope’s initial optics problems became a distant, bad memory.

While much of the subject matter is familiar to those who are familiar with the telescope’s history, there are some interesting gems in the book. Ed Weiler, who was involved with Hubble from his time as a postdoc for Lyman Spitzer—the Princeton astronomer who was the father of the space telescope—in the 1970s to running NASA’s science mission directorate, uses part of his essay to address fellow scientists who criticize NASA’s human spaceflight program. “I have been so intimately involved with the HST for 30 years that when people talk about the separation of robotic and human, I kind of get bewildered,” he writes. “The HST would be an orbiting piece of space junk, frankly, if it were not for astronauts and the Space Shuttle.”

John Grunsfeld, the former astronaut who flew on several Hubble servicing missions (and succeeded Weiler as head of the NASA’s science mission directorate) offers some interesting perspectives from his time on the telescope. Among them is that you can see handprints on Hubble’s exterior from previous servicing missions: “gloves deposit a little bit of material and the solar UV [ultraviolet] radiation then modifies that and incorporates it into a kind of space corrosion.” He wonders, at the end of his essay, if future space telescopes will incorporate some kind of servicing capability as well. “I think that is the grand challenge, and I am very excited and hopeful to remain a part of the outcome.”

| “Griffin’s gutsy decision was more in tune with the idea that safety is the second priority in any bold adventure; having taken all precautions, the first priority is to go, otherwise no explorers would ever have left home,” Dick writes. |

One of the most fascinating essays in the book, though, is not an official part of the symposium’s proceedings but instead included in the book as an appendix. In it, former NASA chief historian Steven Dick examines the decision by NASA in late 2003 and early 2004 to cancel the final servicing mission to Hubble, designated SM4. As Dick writes in the essay’s endnotes, “NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe requested this independent study be undertaken by the author, in his role as NASA chief historian, in order to document in detail the events that led to the cancellation decision.” The original report was completed in late 2004 but published for the first time here, with an update to reflect the move by O’Keefe’s successor, Mike Griffin, to restore that servicing mission.

The timing of the announcement not to fly SM4 coincided with the unveiling of the Vision for Space Exploration, which led many to conclude that Hubble was, in effect, sacrificed to help implement the Bush Administration’s exploration plan. Dick’s essay tells a more nuanced story, where budgetary issues and safety concerns in the wake of the Columbia accident figured into the decision, and a “carefully crafted plan” to announce the mission’s cancellation was undone by leaks to the press around the time of the Vision’s announcement. O’Keefe and other NASA officials argued they were simply implementing the recommendations of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board and creating a “safety culture” in NASA to reduce risk. “Sean feels he is following Admiral Gehman’s report. Sean has been beaten up by Congress,” recalled Weiler in the essay.

O’Keefe’s decision, though, was reversed by Griffin in 2005, and SM4 was flown in 2009 to upgrade Hubble one more time. “Griffin’s gutsy decision was more in tune with the idea that safety is the second priority in any bold adventure; having taken all precautions, the first priority is to go, otherwise no explorers would ever have left home,” Dick writes. Because of that decision, Hubble is alive and well to this day, and, hopefully, for several years to come, serving as both a key tool for astronomers as well as a cultural icon.