The Space Pioneer Actby Wayne White

|

| Companies are unsure of their rights, investors aren’t sure that their investments will be protected, and lawsuits are inevitable if these issues must be resolved in court. |

Bigelow Aerospace is a company that has successfully orbited two inflatable space habitats. Based upon these prototype demonstrations, NASA has awarded Bigelow a contract to install and test an inflatable module on the International Space Station. Bigelow eventually plans to land its inflatable modules on the Moon. The company recently asked the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA/AST) for a lunar “payload review” to recognize ownership of extracted resources by Bigelow and other US firms.

These efforts seek to clarify the law that applies to commercial space activities. A number of intriguing legal questions have remained unanswered since the Outer Space Treaty entered into force in 1967. Can a company mine celestial bodies, and own the resources that it extracts? Are real property rights legal under international space law? What law applies to satellite servicing and removal of space debris? Companies are unsure of their rights, investors aren’t sure that their investments will be protected, and lawsuits are inevitable if these issues must be resolved in court.

Legally, outer space is an international area that is treated in much the same way as international waters in the Earth’s oceans. International treaties govern national activities, and nations are free to enact national laws and regulations that do not violate the treaties that they have agreed to.

There are five United Nations treaties that govern space activities. The 1979 “Moon Treaty” is the only one that directly addresses resource appropriation and real property rights. It prohibits real property rights, and it would establish an international organization to govern resource appropriation. Only 16 nations have ratified or acceded to the treaty, and none of the spacefaring nations are party to the treaty.

The Moon Treaty has no practical effect at present, but two of the nations that are party to the treaty acceded recently, so you can’t quite argue that the Moon Treaty is “dead.” That’s cause for concern. Prohibition of property rights is contrary to western nations’ laws and institutions. And the international resource organization, if ever established, could impose additional costs and regulatory uncertainty upon a nascent industry. The International Seabed Authority, an organization established by the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an example. The Seabed Authority has proposed to the United Nations that it tax deep sea mining activities, an action that they refer to as “innovative financing.” This is hardly an incentive for pioneering work in a difficult environment.

The most broadly accepted treaty, the 1967 “Outer Space Treaty,” is more benign. One hundred nations are party to this treaty, including the United States and all other spacefaring nations. The Outer Space Treaty does not specifically refer to resources or real property rights. However, Article I says that “Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall be free for exploration and use by all States.” Space lawyers generally agree that this freedom of use includes the right to appropriate resources, in much the same way that nations are free to remove fish from the ocean.

There is also some history of resource ownership. The United States appropriated 382 kilograms of lunar rocks during six Apollo missions, and the USSR returned 320 grams to Earth during three Luna spacecraft missions. President Richard Nixon ordered the distribution of fragments of a Moon rock collected during the Apollo 17 mission to 135 foreign heads of state, the 50 US states, and US territories. Each of the fragments were encased in an acrylic sphere, and mounted on a plaque which included the recipient’s flag. No nations objected to the US and the USSR taking possession of lunar rocks and returning them to Earth, and no nations objected to, or qualified their acceptance of the gifts of Moon rocks.

| What about commercial mining of space resources, i.e., the systematic extraction and sale of resources for the purpose of making a profit? Is that legal? |

The United States has adjudicated a court case, the “One Lucite Ball” case, to determine ownership of the moon rock and plaque that President Nixon presented to Honduras. A private party attempted to sell the plaque on the black market, and the US seized it in a sting operation. In a subsequent letter to the US government, the government of Honduras asserted its ownership of the lunar rock pursuant to Honduran law. The United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida, Miami Division, held that Honduras did indeed own the rock, and ordered its return to Honduras (unpublished Case No. 01-0116-CIV-JORDAN).

The Lucite Ball case included in its findings of fact two reports of sales of lunar rock samples, one a slide with specks of lunar dust that sold at Sotheby’s auction for $500,000, and the second the lunar sample and plaque given by the US to Nicaragua, which a Middle Eastern buyer reportedly bought along with some pre-Columbian artifacts for an amount between $5 and $10 million. A more recent Associated Press story (“Moon Chips from Vegas Casino Mogul sent to NASA,” May 23, 2012) reports a different chain of ownership for the Nicaraguan lunar sample and plaque that does not include a Middle Eastern buyer. The article quotes a NASA attorney’s promise that if the lunar sample is authentic, “NASA will return the rock to the people of Nicaragua.”

Because the US District Court did not select the Lucite Ball case for publication, it is not a precedent for subsequent cases in the District of Florida or in any other United States federal courts. However, this court ruling, Honduras’s assertion of ownership, other nations’ failure to object to gifts of Moon rocks, and nations’ failure to object to private sales of Moon rocks, do support an interpretation of the Outer Space Treaty that permits ownership of extracted resources.

What about commercial mining of space resources, i.e., the systematic extraction and sale of resources for the purpose of making a profit? Is that legal? The Moon Treaty does not explicitly say that commercial resource appropriation is legal; this implies that treaty negotiators considered commercial appropriation legal under the Outer Space Treaty. That would be consistent with the rule of international law that says any activity is legal unless it is expressly prohibited. The Moon Treaty does say that “States Parties may in the course of scientific investigations… use mineral and other substances… in quantities appropriate for the support of their missions.” Other clauses in the Treaty say that commercial appropriation is not permitted until the international resource organization is established, and only after that organization approves commercial ventures on a case-by-case basis.

I believe that the resource provisions in the Moon Treaty are bad policy. Limiting resource appropriation to the amount necessary to support an individual mission means that each mission must purchase and transport its own equipment if it wishes to mine and process materials. Allowing unfettered commercial appropriation, on the other hand, would allow all sorts of specialized activities to take place without the necessity of each individual mission having to mine and process its own resources. Mining ice and processing it into hydrogen and oxygen could supply fuel depots, and enable service companies to boost dead satellites to parking orbits, refuel active satellites, recharge life support systems, clear orbits of debris, and fuel transportation in the Earth-Moon system.

The resource provisions in the Moon Treaty are based on a terrestrial frame of reference—an assumption that resources are limited. But space resources are not limited; they exist in vast quantities throughout the universe. The Moon Treaty is also based on an assumption that countries with large, expensive space programs are the only nations that will benefit from space resources. That view implicitly assumes that technology will remain static, that launch costs will not change, and that nations that don’t have space programs will not have access to space.

I don’t agree with that view. SpaceX has demonstrated that significantly lower launch costs are possible, and it is selling its launch services to a wide variety of international customers. Other companies are developing launch vehicles, and there are already two space mining companies. This competition should bring the cost of acquiring space resources within the reach of even the poorest nations.

As we consider a new frontier with abundant resources, we must change our frame of reference. As resources on Earth become increasingly difficult and expensive to mine, and as the need for orbital debris removal becomes increasingly critical, it is clear that our laws and policies must encourage appropriation of space resources. Enacting a mining law which addresses all aspects of resource extraction is one way to encourage commercial activity. The General Mining Act of 1872 is a good model, as it does not include mineral leasing or royalties, which would violate the Outer Space Treaty.

| As resources on Earth become increasingly difficult and expensive to mine, and as the need for orbital debris removal becomes increasingly critical, it is clear that our laws and policies must encourage appropriation of space resources. |

Real property rights is another way to encourage commercial activity. Article II of the Outer Space Treaty says that “Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.” Sovereignty is a bundle of national rights that includes, among other things, authority over territory, jurisdiction to enact and enforce laws, jurisdiction to adjudicate disputes, authority to exclude foreign nationals from areas where they might interfere with activities or threaten safety, and the authority to defend citizens and property.

All of these rights are granted by the Outer Space Treaty, except for authority over territory. Article II of the Treaty prohibits territorial sovereignty. Article VIII confers jurisdiction to enact and enforce laws, and to adjudicate disputes. Article III says that “States… shall carry on activities… in accordance with international law, including the Charter of the United Nations.” The right to exclude foreign nationals to prevent interference and ensure safety is an inherent attribute of national sovereignty as it is defined in international law, so this right is incorporated by Article III. The right of national defense is set forth in Article 51 of the UN Charter, and the right to defend citizens and property is a sovereign right in international law, so this right is also incorporated by Article III.

The right to exclude people and vehicles to prevent interference, and to defend people and facilities against safety threats is in part expressed through the concept of a “safety zone.” Safety zones are areas where the operator of a facility exercises control over navigation of vehicles in the vicinity of the facility, and in which it may exclude vehicles, equipment, and people to ensure the safety of the facility and its occupants. Examples of this concept are the safety zones around oil rigs on the continental shelf, and the International Space Station’s control zone. Space lawyers of various nationalities have written in favor of formalizing safety zones (or in the case of Russian authors, “keep out zones”), and I am not aware of any space lawyers who have argued against the concept.

In the years since the Outer Space Treaty entered into force, several proposals for space property rights have been publicized. All of these proposals would confer permanent titles to territory without requiring the actual presence of people or facilities in areas where some or all of the title is conferred. These proposals violate the Outer Space Treaty because parties to the Outer Space Treaty only have jurisdiction over space objects, personnel, and safety zones. Parties have no jurisdiction to grant or recognize permanent titles to territory.

In 2000, Gregory Nemitz registered a claim to Asteroid 433 Eros. Mr. Nemitz did not claim private ownership of extracted resources; he claimed real property rights over the asteroid as whole. Mr. Nemitz registered his claim on a website maintained by the Archimedes Institute, an organization that takes no position regarding the validity of such claims.

After Mr. Nemitz registered his claim, NASA landed the NEAR Shoemaker spacecraft on Eros, and Nemitz submitted an invoice to NASA for parking and storage fees. NASA and the State Department denied Nemitz’ claim. In NASA’s final agency decision, a former General Counsel of NASA said Nemitz’s “individual claim of appropriation of a celestial body (the asteroid 433 Eros) appears to have no foundation in law. It is unlike an individual’s claim for seabed minerals, which was considered and debated by the U.S. Congress that subsequently enacted a statute, The Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resource Act… expressly authorizing such claims. There is no similar statute related in outer space. Accordingly, your request for a ‘parking/storage fee’ is denied.” (http://www.orbdev.com/010409.html)

Nemitz then filed a lawsuit, arguing that the United States had occupied his property without just compensation. The Federal District Court for the District of Nevada granted the US Government’s Motion to Dismiss, and said that Nemitz did not prove that he had any property rights, so there was no basis for compensation. The Court also ruled that “neither the failure [of] the United States to ratify the… Moon Treaty, nor the United States’ ratification in 1967 of the… Outer Space Treaty, created any rights in Nemitz to appropriate private property rights on asteroids.” Nemitz appealed the case to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and that court affirmed the lower court’s dismissal of the case “for the reasons stated by the district court.”

These courts did not certify their opinions for publication, so these cases do not establish a binding legal precedent. However, in the opinion of the former General Counsel of NASA, some form of property rights may be permissible in outer space, perhaps similar to the rights granted by the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resource Act (30 USC § 1401 et seq.)

Because the Outer Space Treaty does not permit full-fledged territorial property rights, some people say that the spacefaring nations should withdraw from the Outer Space Treaty and make claims of territorial sovereignty. I believe, however, that there are many reasons why spacefaring nations should not take this course of action:

- The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, where the Outer Space Treaty was negotiated, operates on the basis of consensus. In light of the Committee’s past experience, I expect it will be very difficult to achieve consensus in support of any other comprehensive treaty that might replace the Outer Space Treaty.

- Withdrawal from the Outer Space Treaty, followed by territorial claims, would almost certainly lead to strong political opposition, and I would not expect any other nations to recognize such claims.

- The modern standard for establishing territorial sovereignty, “effective occupation,” requires national defense of territorial borders, which would be very expensive.

- History shows that competition for territorial claims often leads to war.

- The Outer Space Treaty has no provisions for taxation, technology transfer, and expensive governing bodies (unlike the Moon Treaty).

- There is little in the Outer Space Treaty that is really objectionable. For the most part the treaty lets nations govern their own activities, subject to general principles that they already subscribe to.

A realistic approach to property rights, and the path of least political resistance, is to adopt a system consistent with the terms of the Outer Space Treaty. I have proposed that the United States and like-minded nations enact national legislation establishing systems of property rights that do not assert jurisdiction over territory. These laws would only grant title to entities that actually occupy outer space and celestial bodies, and would grant to private entities no more rights than those rights conferred upon nations that are party to the Outer Space Treaty. The property rights would only encompass the area actually used, plus a safety zone, and they would only be valid for as long as the area is occupied by people and/or facilities. In all other ways, these rights would be identical to real property rights on Earth—properties could be sold, inherited, and serve as collateral for financing.

| A realistic approach to property rights, and the path of least political resistance, is to adopt a system consistent with the terms of the Outer Space Treaty. |

Participating nations would honor other nations’ property rights pursuant to reciprocity provisions in their property statutes. This approach follows the example of the United States’ Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Resources Act, and similar laws enacted by the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union in 1981 through 1983. Each of these laws have reciprocity provisions that say they will honor the claims of other nations that enact similar laws. In the same manner, the US and other nations could collaborate and coordinate the establishment of an international system for reciprocal recognition of space property rights, including jurisdiction over safety zones.

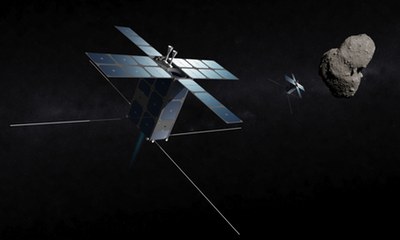

A third way to encourage commercial activity is through space salvage law. The space community has grown increasingly concerned about orbital debris in recent years, but the prospect of capturing, and de-orbiting or recycling satellites, and destroying smaller debris, raises many legal questions, particularly when the parties and space objects are of different nationalities. Satellite and space-vehicle refueling, repair, and upgrade activities could also benefit from greater legal certainty.

The risks posed by space debris provide considerable incentive for its removal, but the cost of such operations may be prohibitive. Such costs might be offset, however, if the entity removing the debris received some or all of the economic benefit derived from that debris.

Ocean salvage operations are analogous to space salvage operations, so ocean salvage laws provide a convenient model for outer space. US law defines salvage as “the compensation allowed to persons by whose assistance a ship or her cargo has been saved, in whole or in part, from impending peril on the sea or in recovering said property from actual loss as in cases of shipwreck, derelict or recapture.” The only instance in which the salvor would become the owner of salvaged property would be in those cases where the property has been abandoned, or when it is unidentifiable flotsam and jetsam. In those instances the property is deemed to have returned to a state of nature, and the first person to find it and reduce it to actual or constructive possession becomes its owner. This is known as the law of finds. In the absence of express abandonment by the property's owner, United States courts have only found abandonment when adjudicating salvage of long lost wrecks.

Like the space mining and real property laws that I’ve proposed above, space salvage laws would be based upon the jurisdiction conferred by the Outer Space Treaty. Only identifiable objects can be the subject of national jurisdiction. Unidentifiable debris would be considered abandoned, returned to a state of nature and subject to appropriation or destruction by the first to find it. Inoperative, identifiable space objects, however, should never be classified as abandoned, to ensure that nations remain responsible for liability under the Outer Space Treaty.

Space salvage laws can permit salvage of government-owned and private space objects, while still addressing concerns regarding national security and technology transfer. Nations can specifically allow contract salvage of space objects on a case-by-case basis. Activity within safety zones would only be permissible pursuant to the terms of a salvage contract, and any unauthorized foreign activity within safety zones would be a violation of national sovereignty. National export control laws would address issues of technology transfer.

Nations can add a column to their registries of space objects, wherein they identify objects that are available for contract salvage, and objects that are subject to related mining and property-rights claims. I anticipate that the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs would cooperate and add an identical column to their international registry of space objects.

| The Space Pioneer Act is something we can do right now, to provide for our future. |

There is historical precedent for the laws that I’m proposing. Homesteading acts were a principal factor in the settlement of the western United States. Among the most successful laws in US history, these laws remained in effect for over a century, until the last homesteading act for Alaska left the United States Code in 1986. The General Mining Act of 1872 is still in effect. Basing space laws on analogous terrestrial laws will make the outcome of legal disputes more predictable, as courts can look to terrestrial law for precedents. Also, nations can implement these laws at no cost to taxpayers, because the only costs are administrative, and these costs can be recovered through filing and processing fees.

I therefore propose that the United States enact a “Space Pioneer Act” that would include real property rights, mining law, salvage law, safety-zones, and reciprocity provisions. I encourage like-minded nations to collaborate with the US and enact similar laws. The Space Pioneer Act is something we can do right now, to provide for our future.