Interstellar versus interplanetaryby Jeff Foust

|

| Caltech physicist Kip Thorne, an executive producer, ensured that the depiction of black holes and wormholes was as scientifically accurate as possible given the current state of knowledge about them. |

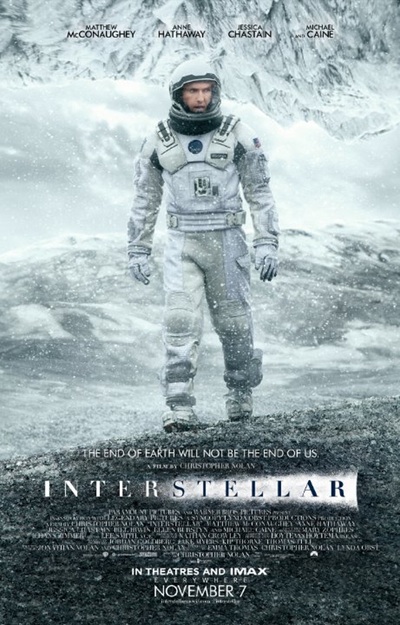

Condensing the plot of Interstellar into a paragraph or two is no easy feat. In the near future on Earth—no time is given but it appears to be a few decades in the future, even though the film has a very contemporary feel—climate change and blight are threatening humanity’s very existence. Society has focused on agriculture to try and grow food—pretty much corn, and nothing but—giving up everything from militaries to space exploration in the process.

Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), a NASA astronaut-turned-farmer, is eking out such an existence when he and his daughter discover odd signals in their home, including coordinates that lead them to a secret base. Here, what’s left of NASA is trying to implement a plan to save civilization by using a newly discovered wormhole near Saturn to go to worlds around other stars, in hope of finding a new home. If one of those worlds is promising, and if scientists can find ways to manipulate gravity, then at least some fraction of humanity could migrate to that new home. There’s also, of course, a Plan B.

The publicity blitz in advance of the film’s release emphasized their commitment to realism. Caltech physicist Kip Thorne, an executive producer, ensured that the depiction of black holes and wormholes was as scientifically accurate as possible given the current state of knowledge about them. Yet, many viewers may be confused about them, or the attributes of relativity that play roles in the film’s plot. That can become hard to follow in the latter stages of the film, as Cooper and astronauts explore worlds on the other side of wormhole, while his daughter—now an adult and physicist—attempts to crack the code of gravity on Earth.

There is, though, another issue—or, possibly, a subtle argument made by the filmmakers—that has received far less discussion than debates about relativity or the movie’s plot direction. Even without the wormhole, the space technology presented in Interstellar is relatively advanced. Endurance, the spacecraft that Cooper et al. use for their titular journey, is a large vehicle with a rotating ring to provide gravity and an impressive propulsion system: it can travel from Earth to Saturn in about two years. The “Ranger” shuttlecraft that they use to travel between Endurance and the planets they visit is perhaps even more advanced: the sharply-angled craft was capable of landing on planets with surface gravities greater than the Earth and taking off again, without staging or refueling.

At the same time, Interstellar is set in a time when humanity had largely turned its back on the cosmos. NASA is working in secret—although conveniently hidden away a few hours’ drive from Cooper’s farm—and publicly presumed to be out of business. In one scene, a teacher tells Cooper that textbooks now state that the Apollo landings were faked as part of an American effort to bankrupt the Soviet Union. (There is a passing reference to tractors using GPS, so there is at least some use of space assets in this society.)

| Between the Rangers and Endurance, it would appear that later 21st-century society would have some of the essential tools needed to unlock the resources of the solar system. Why didn’t they? |

So, in this future era depicted in Interstellar, humanity has turned away from space, but only after achieving some long-desired breakthroughs in spaceflight. After all, the Rangers are, in essence, single-stage-to-orbit vertical-takeoff-and-landing (vertical-landing-and-takeoff?) launch vehicles, capable of carrying several people and requiring virtually no turnaround labor between flights. (Although, oddly, a Ranger is launched from the Earth carrying Cooper and his crewmates on top of a rocket that looks like a vintage Saturn.) And Endurance, capable of going to Saturn in two years, presumably could make a trip to Mars in weeks—another holy grail of spaceflight.

Between the Rangers and Endurance, it would appear that later 21st-century society would have some of the essential tools needed to unlock the resources of the solar system: easy access to and from planetary surfaces, and rapid interplanetary transportation. With those capabilities, society should be able to access the resources of the Moon and near Earth asteroids, and establish habitats there or on Mars—or elsewhere in the solar system, for that matter. At worst, these could make it easier for part of humanity to escape Earth; at best, they could help solve Earth’s problems.

Yet, that line of thinking is ignored in the film. Perhaps these technologies are too expensive. Yet, if they’re at least feasible, then the next step is to find ways to make them more affordable, particularly if the future of humanity is on the line. Other locations in our solar system are certainly far less hospitable than the Earth, but then, so are water worlds with kilometer-high waves or icy planets with frozen clouds depicted in the movie. While Earth is in peril, the rest of the solar system is unaffected by its impending ecological doom.

Or, perhaps most disappointingly, the writers of Interstellar fell back on common science fiction tropes: shuttlecraft that flit effortlessly between planets and space are a staple of such movies and television shows, for example. For all the effort they put into getting the science of Interstellar right, they appear to have spent far less on the technology—or, at least, thinking through the implications of the technology they use.

This doesn’t make Interstellar a bad movie. It’s visually stunning, particularly when viewed in IMAX, and despite its length it doesn’t feel like a long movie. Hyped as a great movie, it is perhaps a pretty good movie: a disappointment given the expectations, but something that may yet stand the test of time. One wonders, though, what epic tale of interplanetary exploration, one with the movie’s technology, but not its wormholes, the producers could have conceived instead.