Names in bottles: a new tool for exploration?by Dan Lester

|

| I was led to believe that as a result of putting my name there, I would feel more involved in space exploration. I’m frankly still waiting for that to happen. |

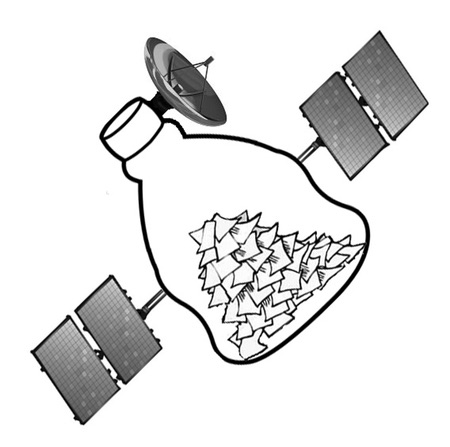

The outreach strategy of inviting people to put small digital pieces of themselves on space missions is one that generates good response. Most opportunities have been for NASA missions, but ESA and JAXA have offered some as well. Most have been planetary/small body missions or, more generally, planet-related missions such as Kepler. That is probably because such objects are considered more tangible cosmic destinations for humans than an active galaxy or a coronal hole. Most allow just a dozen or so bytes for a name, but a few missions were somewhat more generous about solicited digital content. The “Face In Space” opportunity had STS-133 and -134 Space Shuttle missions carry digital images uploaded by the public. Cassini carried to Saturn more than half a million digitized signatures and even some digitized paw prints from beloved pets.

Some thirty missions have offered this personalization opportunity to the public thus far. Most of these names are in space, but unfortunately some are at the bottom of the ocean (e.g. Mars 96/MAPEx). Millions of people have participated. We are even now being offered a multi-legged trip: send your name on the maiden flight of Orion, and it will be returned to be eventually shipped out “to destinations beyond low-Earth orbit, including Mars.” That makes it planet-related. You even get a “boarding pass” to prove you did it. You might even get a transfer stub. Mark Geyer, NASA’s Orion program manager, says, “Flying these names will enable people to be part of our journey.”

The idea for this outreach device no doubt looks to the Voyager Golden Record as a historical model. While the Pioneer spacecraft were equipped with small metal identification plaques with illustrative sketches, and likely included some inconspicuous autographs from the mission team, the Voyager record had a more ambitious message to deliver to intelligent beings that might recover it. This record included sounds and images selected to illustrate the diversity of life and culture on the Earth. While the content was analog, it was probably equivalent to around a gigabyte of digital data. It was not about individuals, but was a strong personalized message from our species. It was a piece of “us” heading out towards the stars.

With dramatic increases in data storage density, people quickly realized that sending reams of personalized stuff was cheap and easy, and, unlike with the fairly sizable Golden Record, could include much more information in a chip that weighed on the order of one gram. Plans are afoot to use 100 megabytes of the New Horizons memory (about one percent of the total) outbound after the Pluto encounter to record, in the tradition set by Voyager, an updated crowdsourced message from humanity to the cosmos, perhaps including both pictures and sounds. This message would also include several thousand names. Since the voyage has no foreseen ending, that opportunity offers some semblance of immortality.

It would appear that offering people the opportunity to fly their names is an attempt by space agencies to give the public some low cost, low commitment sense of involvement in a space mission, and is a device to articulate support. At some level, a long list of such names can demonstrate public enthusiasm about a mission. The Internet offers a medium by which such digitally encoded names can be collected with great efficiency, and many millions of names can be archived on a chip whose contribution to the spacecraft mass and power budget is negligible. It is, to the space agencies at least, a crowdfunding enterprise, where the unit of value is a name of an interested party.

| Sending a piece of yourself with an explorer for the purpose of making yourself a part of the exploration is very different than getting a souvenir or keepsake back from that exploration. It is hardly a remembrance for the explorer because, frankly, robotic space science explorers do not pine for such remembrances. |

The historical trope of explorers carrying memorabilia and mementos is longstanding. In large measure, these items were taken as personal remembrances of home for the travelling explorer, rather than as things to be cherished upon return. Admiral Peary did, however, bring flags to the pole from the Peary Arctic Club and the Explorers Club that would be returned to them at the end of his expedition. Of course, NASA astronauts took with them items that became highly valued “space flown artifacts”, including many that were planned as such. For Apollo, these included commemorative silver medallions, tiepins, postal covers, flags, and even miniature lunar roving vehicle license plates. Of course, all the returned astronaut personal equipment (even toothbrushes, combs, and shaving utensils), writing instruments, checklists, and flight data files became valued items in themselves as well. But none of these were personalized for people who didn’t go. Historical explorers brought back tokens of the trip for their admirers, and assistants. Peary did so in the form of fox pelts. This was all about getting back some materiel that had been there, and not a symbol of a person who had not gone. With the possible exception of Charlie Duke’s family photo that he intentionally left on the Moon, personalized physical tokens sent were assumed to be returned. But most of the names we are sending now on at least robotic science missions will not be returned.

Sending a piece of yourself with an explorer for the purpose of making yourself a part of the exploration is very different than getting a souvenir or keepsake back from that exploration. It is hardly a remembrance for the explorer because, frankly, robotic space science explorers do not pine for such remembrances. Even human explorers are not likely to derive solace by fondling a flash memory chip. The idea that this is about attaching yourself to what may—someday—be considered a historical space antique by future collectors also seems somewhat sketchy. It does not speak to any role you played in the mission. In that sense, it would not be much of a memento. Of course, the collectors would have to have the technical sophistication to read it, and would need some understanding of UTF-8 or ASCII encoding to interpret it. I offer the term “particimento” to describe what this is about. It is about sending with the expedition a memento of personal participation. Just a symbol. Maybe it is a simple “my good thoughts are with you” kind of token.

The idea of sending people’s names with explorers, whether digitized or in hard copy, does not have much historic precedent. That is, if the goal is to kick up interest in an exploration, historic explorers did not do it that way. Taking names with them to enable people to be part of the journey was evidently not important to them. Now, many historic explorers were mass-constrained, much as contemporary space missions are. It is unlikely that Lewis and Clark, Stanley, Peary, or Scott would have hauled with them thick volumes filled with signatures. (Though Scott is known to have hauled Champagne on his ill-fated Terra Nova mission to the South Pole.) But shipborne or airborne explorations could have easily done so. Even mass-constrained explorations could have tucked away a small notebook filled with tiny signatures of royalty, or of esteemed members of national societies that underwrote their travels. Such a notebook of particimentos could have been proudly displayed upon return.

Of course, instead of just hauling names along, these explorers put names of their patrons on the maps of geographical features they discovered. Why, these historical explorers could have collected real pieces of people, rather than just sequences of letters. Lewis and Clark could have carried with them a vial of fingernail clippings or strands of hair, donated by an adoring audience. If they were returned, the identification of each piece, of course, would have been problematical, but would be much easier now, encoded in the DNA, probably with far more specificity than any alphameric name.

I have to think that the lack of historical precedent for particimentos says something about our cultural evolution: that historic cultures perhaps saw exploration somewhat differently than we see it today. That is, did Lewis and Clark not tuck away a notebook of congressional signatures in their brave push across the continent because they just did not think about it, or because they thought it was a dumb idea? Certainly federally funded expeditions require deep public support. But, for goodness sake, you could stash the names of every single US taxpayer in a miniscule flash memory cell on one of these modern space missions. You could bring along everyone who is paying for it, thereby thanking them for it!

The particimento fad is certainly enabled by the way that our culture has evolved to embrace digital and online identity. We are now more accepting that a handful of coded bytes can really represent us. When our identity is stolen online, the thieves are not taking us. They are using a digital representation of us.

Now, I do not want to come across as being overly critical of this novel and innovative outreach device. So don’t complain that I am. It does not work much for me, but could well energize and inspire others. It might work for you. To each his own.

| Real support could be better achieved by telling congressional representatives about the importance of such missions, or informally teaching kids about them. Or, perhaps offering real money in a crowdfunding effort. |

It may well be a generational thing. Younger people are certainly more accepting of their identity and perhaps even their excitement being symbolized in a written code that could be manifested digitally. The idea that tokens of good thoughts could be relevant to a robotic mission is certainly a wired-generation type of conviction. My point here is that the device is one that could have been used to try to energize and inspire supporters of historical exploration in olden times. I do not believe it was. Our collective enthusiasm for it now may reflect the evolution of our cultural sense of identity.

I will say that, as a device to assert support for a mission, attaching your name to it in a highly inconspicuous and rationale-free way is of questionable value, and somewhat artificial, though at nearly zero cost. Of course, we could all just jump up and down and let out a big cheer for the mission instead. Even just as a feel-good device to garner the impression of personal involvement, it is really pretty thin, and the take-away is perhaps just a receipt. Real support could be better achieved by telling congressional representatives about the importance of such missions (an option which legally cannot be recommended by NASA), or informally teaching kids about them. Or, perhaps offering real money in a crowdfunding effort. Just some casual remarks to friends about the importance of space exploration between beers at a social event could have more far-reaching value than stuffing your encoded name on a chip in a spacecraft. In this respect, the entreaty from the Orion program to “tell your friends to come along!” is probably a constructive one.

The particimento phenomenon is an engaging one. I think that it points to ways that our culture has evolved with regard to the excitement of exploration. In the same way that we do not explore in the way we used to explore, we do not really express our enthusiasm about exploration in quite the same way either.