Witnesses: Space historiography at the handover (part 3)by David Clow

|

| The missed opportunity here is not just in blurring the details of Apollo, but in failing to see the crucial lessons of character that Glynn Lunney called a “code of ethics” and a “system of thought.” |

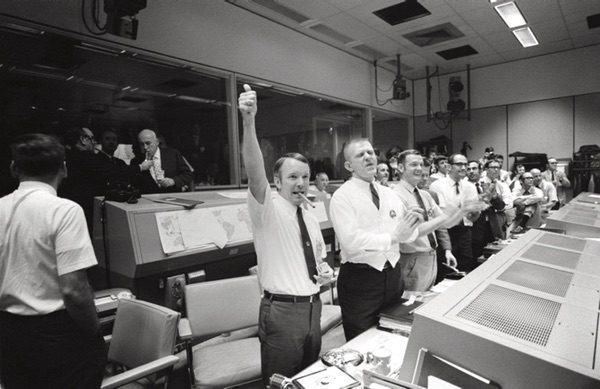

“A pastiche of knowledgeability”: in Kraft’s MOCR, it was dangerous. Today’s version can make a career instead of ending it.2 The danger is that someone, say a middle school student, views a bluff and repeats it as authentic. The greater danger is that the student’s teacher repeats it too, and as that middle-school class hears it, incorrect history becomes the only history they know.

The missed opportunity here is not just in blurring the details of Apollo, but in failing to see the crucial lessons of character that Glynn Lunney called a “code of ethics” and a “system of thought” (see below.) For the best of the flight controllers, Mission Control was more than a job. It was a calling. Kennedy’s challenge for them was personal. They sought it because making history in the first person organized and measured the best of their own energies and skills.3 The personal tests they undertook, the standards they set, permitted them a hard-earned esprit de corps, and it required them to be merciless in pursuit of fact starting with themselves, with no excuses: after Apollo 1, Chris Kraft remembered, “Now we’d put three astronauts into harm’s way and made their escape impossible. They were dead and we knew that it was our fault.”4 Gene Kranz’s talk with his team after the fire was penitential self-flagellation:

Spaceflight will never tolerate carelessness, incapacity, and neglect. Somewhere, somehow, we screwed up. It could have been in design, build, or test. Whatever it was, we should have caught it. We were too gung ho about the schedule and we locked out all of the problems we saw each day in our work. Every element of the program was in trouble and so were we. The simulators were not working, Mission Control was behind in virtually every area, and the flight and test procedures changed daily. Nothing we did had any shelf life. Not one of us stood up and said, “Dammit, stop!” I don't know what Thompson’s committee will find as the cause, but I know what I find. We are the cause! We were not ready! We did not do our job. We were rolling the dice, hoping that things would come together by launch day, when in our hearts we knew it would take a miracle. We were pushing the schedule and betting that the Cape would slip before we did. From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: “Tough” and “Competent.” Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do. We will never again compromise our responsibilities. Every time we walk into Mission Control we will know what we stand for. Competent means we will never take anything for granted. We will never be found short in our knowledge and in our skills. Mission Control will be perfect. When you leave this meeting today you will go to your office and the first thing you will do there is to write “Tough and Competent” on your blackboards. It will never be erased. Each day when you enter the room these words will remind you of the price paid by Grissom, White, and Chaffee. These words are the price of admission to the ranks of Mission Control.5

As the AHA pursues rigor for the profession, presumptive historians have no such obligation to accountability. “The encouragement of better scholarship needs to come from those organizations that have a real focus on specifics,” Seth Denbo said. “AHA can say that good history should be peer-reviewed until we’re blue in the face, but the policing, for lack of a better word, needs to happen at the level of the groups of specialists in the historical sub disciplines.”6 In space historiography’s current state at this handover, absent what Glynn Lunney called the MOCR’s “system of thought,” the policing cannot happen. Whether such a system of thought is even possible today is a question. Meanwhile, it compromises America’s future in space to neglect the ethos that brought it this far, and neglecting it deliberately today is the same thing it was when young men in Mission Control relied implicitly each other’s character: a breach of professional trust, and even something like a personal moral transgression.

Mission Control as a system of thought

Embrace of fact; testing to proof; deliberation; strict adherence to sequence and continuity; conciseness; consensus; elimination of assumption and guessing; eradication of deceit, rationalizing, and ulterior motives; personal integrity, mutual trust and accountability; the esprit de corps of “brother flight controllers, united in a common goal”7 rested on attitudes. Glynn Lunney related how Mission Control’s success was erected day-by-day on this foundation.8

[W]e began to build what—our technical term is mission rules. I think of it as a code of ethics. We began to build something so that, when we flew, we and the flight crews would know what we were going to do under certain sets of preset circumstances, which allowed us to develop this ethics base for, “Okay, well, if we got into something we hadn’t planned, how far would we be willing to take it?” We found that most of us in responding to circumstances, we’d end up with about the same solution, given the right amount of time to work on it, so that we did have this sort of common base. And we developed it by just starting to sit down and write: What am I going to do if this happens? What if this system fails? What if the trajectory deviates over to this line? What if we lose communications with the crew during ascent, during the powered flight phase of the vehicle, etc.? And then we would write these down and then we would bring them in and we would argue about them—emotionally, argue about them. And it wasn’t like we had the code all figured out before we started writing. We started writing sort of and met in the middle. We started writing and we gradually tested everything and argued about it and decided whether that was really right or not for that “what if” condition. And as we did that from the bottom up, we began to realize that we had a more—that we could capture our more umbrella approach, or a higher-order approach, to this in terms of: How much redundancy do I want to have left to continue? And that became aware of risk versus gain. We had a way then of packaging up at that level and then we began to reflect all these individual rules against this higher order of thought, so that the more that—and we would do that hour after hour, day after day, where we would bring in and argue amongst ourselves and then argue with the next level of people, the Flight Director or the full team, then we would argue and discuss with the crews, and then we would do it all over again when we ran some simulations and tested it.

But we gradually built this very strong, common understanding of: how far were we willing to go; and when would we pull back? You know, stop doing something. We developed this so that—and it served us well, Roy, because we encountered a lot of different things, especially in Gemini and then in Apollo, where the communications amongst people and the decision processes that were going on in people’s head was almost like—it was almost like a—Star Trek calls it a “mind meld” or something like that. But we knew what we were thinking without even having, perhaps, to express the full thought. And everybody, everybody—the crews, the folks in the Control Center—got comfortable that we kind of knew how far we were willing to go, both for the cases we had defined, the what-if’s, the mission rules, and that provided then a basis for us to respond to whatever else might happen in flight. And we generally would arrive at about the same answer, given the same def—

[Roy] Neal: You wrote them—

Lunney: —definition of problem.

Neal: —so well that they’re still in effect today, are they not?

Lunney: Still in effect. And they continue to be tweaked and tuned, but fundamentally, they haven’t changed very much. And the other thing that happens is, as a result of this documenting, testing, melding, arguing, and then fitting it into some higher-order way of thinking about them, became a system of thought for us.9

(Gene Kranz pointed out in his July 5 email to the author, “Mission rules are not unique to Spaceflight. Every time an aircraft flies they have to comply with the Master Minimum Equipment List (MMEL)… In flight test we used an MEL augmented by procedures… when I wrote the rules for Mercury I used the flight test MEL procedures as the starting point.”)

Foundations of Mission Control and the AHA Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct

“History is the never-ending process whereby people seek to understand the past and its many meanings.” That quote, which might have described the events in the MOCR as the Flight Directors got their teams on track to save Apollo 13, comes from the American Historical Association’s Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct. The AHA’s standards are remarkably consistent with Gene Kranz’s “Foundations of Mission Control,” and with the ethos Chris Kraft laid down at the beginning.10,11

| The AHA’s standards are remarkably consistent with Gene Kranz’s “Foundations of Mission Control,” and with the ethos Chris Kraft laid down at the beginning. |

For example, the AHA seeks to: “Develop a culture of disciplined learned practice. “Kranz’s “Foundations” requires: “Discipline- Being able to follow as well as lead, knowing that we must master ourselves before we can master our task.”

The AHA obliges historians to: “Cultivate mutual trust and respect; and unite in defense of the integrity to the record.” “Foundations” demands: “Competence- There being no substitute for total preparation and complete dedication, for space will not tolerate the careless or indifferent.”

(Jerry Bostick recalled, “Us guys in the Trench were sometime accused of being arrogant, but as John Llewellyn, the Retrofire Officer, used to say, ‘If it’s true it ain’t braggin’.’ It was good for the new guys we brought in. They felt the feeling of pride in working in the Trench: ‘I’m working with the best bunch of guys in the world; I’m not going to let them down.’”)12

The AHA seeks to: “Create a culture of candor and accountability in pursuit of quality in performance.” “Foundations” requires: “Toughness- Taking a stand when we must; to try again, and again, even it means following a more difficult path.”

The AHA emphasizes: “Historians celebrate intellectual communities governed by mutual respect and constructive criticism.” “Foundations” mandates: “Teamwork- Respecting and utilizing the ability of others, realizing that we work toward a common goal, for success depends on the efforts of all.”

(BOSTICK: It was a real team atmosphere. It was that way with the managers, it was that way with the flight crew. I mean, they would tell you in a minute. Boy, I mean, I've had a number of astronauts tell me, ‘I respect you guys for what you do in the control center, your job. I wish I understood all that. I wish I could do it. I feel kind of bad because here we are getting all of the credit and you guys do all of the work.’ It was just real teamwork.)13

The AHA demands: “All historians believe in honoring the integrity of the historical record. They do not fabricate evidence. Forgery and fraud violate the most basic foundations on which historians construct their interpretations of the past. An undetected counterfeit undermines not just the historical arguments of the forger, but all subsequent scholarship that relies on the forger's work. Those who invent, alter, remove, or destroy evidence make it difficult for any serious historian ever wholly to trust their work again. […] The real penalty for plagiarism is the abhorrence of the community of scholars.” “Foundations of Mission Control” holds the MOCR to a standard of: “Responsibility- Realizing that it cannot be shifted to others, for it belongs to each of us; we must answer for what we do, or fail to do.”

The AHA says: “Honoring the historical record also means leaving a clear trail for subsequent historians to follow.” In the MOCR the value of this was demonstrated the moment the trainee said, “I don’t know where to start.”14

The AHA’s mandate: “Scholarship—the discovery, exchange, interpretation, and presentation of information about the past—is basic to the professional practice of history….Good teaching entails accuracy and rigor in communicating factual information, and strives always to place such information in context to convey its larger significance. Integrity in teaching means presenting competing interpretations with fairness and intellectual honesty.” This was achieved in Mission Control through endless drills from which mission rules were formulated.

The AHA says, “Professional integrity in the practice of history requires awareness of one's own biases and a readiness to follow sound method and analysis wherever they may lead.” Kranz told his team, “Mission Control will be perfect.”15

And only so could the Mission Control teams claim for themselves, and thus could promise to deliver to their mission and to history: “Confidence- Believing in ourselves as well as others, knowing that we must master fear and hesitation before we can succeed.”

Res Gesta Par Excellentia: Stewardship of the “Imagination Portal”

The purposes of both charters go beyond mere job performance. As Kranz concluded in “Foundations”, the real objectives were:

- To instill within ourselves these qualities essential for professional excellence.

- To always be aware that suddenly and unexpectedly we may find ourselves in a role where our performance has ultimate consequences.

- To recognize that the greatest error is not to have tried and failed, but that in trying, we did not give it our best effort.16

Space historians today inherit a record that is huge, comprehensively detailed, documented and date-stamped, archived and curated (Oxygen Tank No. 2 was serial number 10024X-TA0009)17; and also flawed and skewed because it the fabric of it was woven by people. Apollo was a human enterprise. So are understanding and explaining Apollo.

| “ I think one of the problems in recounting Apollo history is that after forty years, memories can fade or change. I’m sometimes reminded by my Apollo colleagues of a detail I had totally forgotten.” |

The “overview effect” is the enlightenment an astronaut can experience seeing earth from space,18 but one did not have to be aboard Apollo 8 to experience a conversatio morum from Bill Anders’ Earthrise. The men in the MOCR felt that the work they did and the experience they shared changed their lives. Every version of that change was as different as the people who experienced it. For example, Gerry Griffin reflected,

When I was younger I remember listening to the veterans from World War II as they talked about their war time experiences, and I always assumed that if they were there, then their accounts had to be accurate. But, as I’ve grown older I understand now that memory isn’t always like that. I think one of the problems in recounting Apollo history is that after forty years, memories can fade or change. I’m sometimes reminded by my Apollo colleagues of a detail I had totally forgotten. And the passage of time often tends to magnify or distort things as you try to remember the distant past. I’ve read how some of the guys in the Apollo MOCR said they were aware of the historical significance of it all. I’m sure they are being completely honest, but I have a slightly different take on it. Personally, I don’t think I understood at the time how truly significant it really was. We were all young, for one thing; for sure, I knew what we were doing was big and very important for the country…and I also knew it was one heck of a lot of fun! But I don’t think I really understood the historical significance of Apollo until it was all over…or close to over. Maybe sometime between Apollo 11 and Apollo 17 we had enough time to come up for air and reflect on what we’d just done. But prior to that we were so damn busy—in Gemini we flew every six weeks or so, and from Gemini we went straight to Apollo. I remember on Apollo 11 working beside Cliff Charlesworth. I already had been designated lead Flight Director on Apollo 12, and I had no reason to suspect that 11 wasn’t going to work; so even as I was working with Cliff on 11 I was already thinking about Apollo 12. I couldn’t dwell on 11 much because 12 was right behind it--there we were, getting ready to go again. I worked on 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17—never had a break—it was a very intense time. I’d been in a fighter squadron in the Air Force before I got to NASA, and I see the similarities between those two experiences…both had a lot of mission ops crammed tightly together. I can imagine what it felt like to be one of those World War II veterans I listened to, the ones flying B -17 bombing raids over Germany—adrenaline pumping, scared to death—I don’t believe they were thinking “we’re saving the world here.” They were just flying their missions, trying to hit their assigned targets, then make it back home safely. That’s pretty much the way I felt during the Apollo missions.19

Glynn Lunney said,

… I have come to think of the Control Center in Florida, and now especially the Control Center here in Houston, as a kind of a church. It was a cathedral of sorts where we went and did what we thought was important work for our country and for humanity, and we did it in this place where we all came together and struggled, mightily at some times, with the problems that we faced and reaction response that we had to bring to the table. And when I go in the Control Center now, I still have this sense of coming back to the church or the cathedral of my youth where we did important—I don’t want to put a religious word on it—but we felt that we were doing something very, very important—and very important for mankind.20

In a separate interview, Lunney said (in contrast to Griffin),

At least in our case, and certainly speaking for myself, I always had the sense that we were involved in a significant activity of our time, significant for our country and for our country's position in the world, and we were kind of—I've used this term in previous discussions—I've always felt like we were, and I was a steward. I was a small [one], perhaps, but one of the stewards for this program to make it come out right.21

And in contrast to Lunney and Griffin, Gene Kranz said,

I think the discussion of Mission Control as a Cathedral misses the point of our work. Mission Control is The Leadership Laboratory for Spaceflight… There we teach the culture of excellence to our controllers; individually, as a team member and as a leader. We teach them the I and the WE component in a team, because when their time comes we need controllers to step forward, assume a leadership role… and when their work is complete return to the ranks of the team. Our work develops chemistry, because chemistry in an organization is a force amplifier… it amplifies the individual as well as the teams talents and leads to communication that is virtually intuitive because we must know when our team mate needs help or a few more seconds to come up with an answer. Finally, when the time comes for us to act alone in Mission Control… we are never alone…. because we know the team stands with us.22

During his review of this article, Glynn Lunney noted that there was no single “correct” opinion about the “meaning” of the MOCR: “Perhaps that’s the value of landmarks,” he said, “it’s what people make of them, and how they draw their on conclusions.” Lunney reflected on the schoolchildren’s tours that visit Mission Control today, and reflected that “they won’t see the ‘cathedral’ or the ‘Leadership Laboratory’ that it was for us. It’ll be different for them. It’ll be what they make of it. I hope it’ll be an ‘imagination portal’ for them, a place that opens a door their minds and invites them to have great ideas about the future and about their own possibilities” in making the big dreams into big realities.23

| That poor stewardship perturbs the forward momentum so much that we could actually be damaging the future of space exploration by disrespecting its past. We owe the record better than that. |

In inheriting our role as stewards, space historians have the same opportunity to create such portals. To do it, we have to balance passion and fact, big dreams and cold calculations. Certainly the phenomenon of force amplification happens every day in the study of history, both positive and negative, and particularly so with today’s unprecedented technology. Also, our place in our field is an unusual one: historians of space exploration are not just documenters of its past. We are advocates for its future. Like the flight controllers, we participate in an ongoing continuum. We are present in it, seeking in our way to steer it, knowing that what we do affects its direction. There was bedrock in the MOCR, and as different as their experiences of it were, they built on the same foundation of fact. As different as historians’ interpretations of it must be, there is bedrock for us as well. We can find it, or we can just loot NASA’s attic for souvenirs. We can pump up the drama of every mission and chop history into palatable anecdotes for television and Web venues that demand above all else that their content be “easy-to-digest.”24 We can make plaster saints of the people and mythologize the facts into dramatic characterizations. We can play “Telephone” and create an avalanche of what Carl L. Becker called “pale replicas”:

…time passes […]; to-morrow and to-morrow and to-morrow creeps in this petty pace, and all our yesterdays diminish and grow dim: so that, in the lengthening perspective of the centuries, even the most striking events (the Declaration of Independence, the French Revolution, the Great War itself; like the Diet of Worms before them, like the signing of the Magna Carta and the coronation of Charlemagne and the crossing of the Rubicon and the battle of Marathon) must inevitably, for posterity, fade away into pale replicas of the original picture, for each succeeding generation losing, as they recede into a more distant past, some significance that once was noted in them, some quality of enchantment that once was theirs.25

Except that in our time, that petty pace is as fast as the Web, and in our day, with our tools, manufacturing pale replicas of history is an industry.

That poor stewardship perturbs the forward momentum so much that we could actually be damaging the future of space exploration by disrespecting its past.26 We owe the record better than that. Just as important, we owe ourselves better than that. We have the opportunity to inherit—from the source—and to instill within ourselves these qualities that made Apollo possible. That permits space historians to try to be more than just witnesses to it. We can be heirs to the meaning of it. We can respect the bedrock, help to maintain the imagination portal, and perhaps earn what united the MOCR men: the “quality of enchantment,” the sense of purpose and the gratitude that expressed by Gene Kranz: “We were the ones in the trenches of space and with only the tools of leadership, trust, and teamwork, we contained the risks and made the conquest of space possible.”27 And by Glynn Lunney: “So, we loved it. We loved it, we loved the work, we loved the comradeship, we loved the competition, we loved the sense of doing something that was important to our fellow Americans.”28 And by Jerry Bostick, who was there when the Apollo 8 crew read Genesis from lunar orbit: “Thank you, Lord, for letting me be here and be a part of this.”29 And by Sy Liebergot: “Can you say esprit de corps?”30 And by Gerry Griffin in his urge to grapple with “that pressure cooker, split-second, decision-making on the ground.” And by Chris Kraft himself: “So those of us that were allowed to do it, and lucky enough to be present, and were given the opportunity to do it—I'm not trying to be godlike or anything like that—what I’m saying is that we were given an opportunity to do it, and we did it. But that's a characteristic of the American human being. That's what makes us great.”31

Kranz wrote about his version of the handover in an essay, “Our Time”, for Alan Bean’s Painting Apollo.

The handover to a new generation began in the mid 80’s to men and women who shared our energy and passion. They would continue to write the history of space exploration and we wished them well.

Our Time was rapidly coming to an end. There were fewer of us at each Mission Control reunion. The glint remained in our eyes, the stories still rang out, but our edge was now softer and we drank a lot less than in the debriefing parties of our earlier years. Our only regret is that we will not live to once again see an American walk on the Moon. We had grown and lived through three wars, had served and had seen our countrymen die for our freedoms. We lived as explorers and charted America’s path in space. We knew about high risk and grief for our friends who gave their lives to the effort. In the words of Teddy Roosevelt, “We knew the triumph of high achievement, and when we failed, at least we failed while daring greatly. Our place will never be with those cold and timid souls who neither knew victory or defeat.” 32

Not all recorders of history take that option, as Jerry Bostick recalls:

Obviously I think it’s important that the history be documented as accurately as it can be. But you know, the people who will continue to write about it, and unfortunately we all have slightly different memories about it. It’s kind of depressing though when something like this happens—I was in London three or four years ago and people brought a couple of books for me to sign. I said “Gee, what’s this? I haven’t seen this before.” And they said “Well, you’re quoted in there a number of times.” I never could figure out how [the authors of the books] got it until I really read what they had to say. They'd read my oral history from [Johnson Space Center] but I’d have appreciated it if they’d given me a call and asked for more information, or just to confirm. I’m not saying they’re lazy, but—it was mildly offensive, I’d say. It was a direct quote out of the oral history but I thought, why didn’t they give me a call?33

And some do.

Space Hipsters,34 a Facebook group with more than 2,000 members, mentioned recently that Dakota Creek Industries, a shipbuilding and repair facility in Anacortes, Washington, was preparing to celebrate the launch of Auxiliary General Oceanographic Research (AGOR) 28. It was standard press release material, and of interest to space enthusiasts mostly because of the ship’s namesake. One of the group members, a longtime space author and journalist, was up early and online on a Saturday morning in Melbourne, Australia. She followed the link to Dakota Creek Industries’ website, where she read that “The Office of Naval Research (ONR) owned Auxiliary General Oceanographic Research (AGOR) vessels will serve a pressing need for a general-purpose ship based research and provide a platform for oceanographic research. The ships will be managed by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (Massachusetts) and Scripps Institution of Oceanography (University of California, San Diego). AGOR 28 is to be named after the first female astronaut in space, Sally Ride.”35

The writer notified Dakota Creek that “AGOR 28 ‘Sally Ride’ is named after the first US woman in space, not the first woman in space.”

It was Friday afternoon in Washington State, so a contact person was at work at Dakota Creek as the email popped up. This person replied immediately, “Thank you for bringing this to our attention. We will correct our web site to clarify. Please give us a week or so to get this rectified.” The contact person forwarded it up the ladder at the shipbuilder, and replied again to the Space Hipster reader, “I’m sure the Navy and SCRIPPS has everything correct and it was just us but I also let both entities know ‘just in case’ as now is the time all the materials are being printed for the ceremony. Thank you again and personally I appreciate that you corrected us in a gracious manner!”36

That debris was plucked out of orbit before it could do any more damage. Sometimes stewardship is that simple, but you have to be there.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Rod Pyle, Robert Gounley, and Emily Carney for their reviews and suggestions on the drafts of this article. Kate Doolan is the hero of the anecdote at the end. Thanks to Dr. Seth Denbo, Director of Scholarly Communication and Digital Initiatives at the American Historical Association, for his update on the emerging historiography in the digital era. Steven Michael’s photography of the MOCR is gratefully acknowledged.

The Johnson Space Center Oral History Project is already indispensable to historians, and only becomes more valuable with the passage of time. Books such as Murray and Cox’s Apollo, Kranz’s Failure is Not an Option, Kraft’s Flight, Lovell & Kluger’s Lost Moon, and Liebergot’s Apollo EECOM are essential as well.

That said, Jerry Bostick, Gerry Griffin, Glynn Lunney, Gene Kranz, and Sy Liebergot personally gave me more time than they could spare and more insight than I could ever have gotten from using only the written record. Their reviews and comments on this article are greatly appreciated. This is dedicated to them and to their colleagues in the MOCR.

Endnotes

- Karl Taro Greenfeld, “Faking Cultural Literacy”. The New York Times. May 25, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/25/opinion/sunday/faking-cultural-literacy.html?hp&rref=opinion&_r=0. Accessed May 25, 2014.

- Fox’s Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon?, aired twice in 2001 on the strength of heavy promotion, and said no, it was all faked. Feedback ranged from “What a disgusting film,” “FOX' fun for the feeble-minded,” “Pure lies,” and “It's the 'Jerry Springer' of space documentaries...” to “Quite entertaining...,” “I Thought it Was Intriguing,” and “I worked for NASA, now I believe this movie.” Internet Movie Database, Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon? (2001) (TV), Reviews & Ratings. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0277642/reviews?start=10. Accessed May 30, 2014

- John F. Kennedy Moon Speech - Rice Stadium. September 12, 1962. http://er.jsc.nasa.gov/seh/ricetalk.htm. Accessed June 20, 2014.

- Chris Kraft. Flight. My Life in Mission Control. New York: Dutton. 2001. p. 271.

- Gene Kranz. Failure is Not an Option. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2000. p. 204

- Dr. Seth Denbo, Ph.D., Director of Scholarly Communication and Digital Initiatives, American Historical Association. Interview with the author. June 16, 2014.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Harland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 118.

- Glynn S. Lunney. Interviewed by Roy Neal. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 9 March 1998. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/LunneyGS_3-9-98.htm. Accessed May 31, 2014.

- Glynn S. Lunney. Interviewed by Roy Neal. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 9 March 1998. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/LunneyGS_3-9-98.htm. Accessed May 31, 2014.

- American Historical Association. “Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct.” http://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/governance/policies-and-documents/statement-on-standards-of-professional-conduct. Revised2005. Accessed May 14, 2014.

- Kranz, Gene. Failure is Not an Option. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2000. p. 393.

- Interview by the author with Jerry Bostick. May 15, 2014.

- Jerry C. Bostick, Interviewed by Carol Butler. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Marble Falls, Texas – 23 February 2000. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BostickJC/BostickJC_2-23-00.htm. Accessed May 26, 2014.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Harland Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 144.

- Gene Kranz. Failure is Not an Option. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2000. p. 204

- Gene Kranz. Failure is Not an Option. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2000. p. 393.

- Edgar M. Cortright, et al, REPORT OF APOLLO 13 REVIEW BOARD. June 15, 1970. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/apollo_13_review_board.txt. Accessed May 25, 2014.

- The Overview Institute, “Declaration of Vision and Principles.” http://www.overviewinstitute.org/about-us/declaration-of-vision-and-principles. Accessed June 8, 2014.

- Interviews by the author with Gerry Griffin, July 22, 2014, August 15, 2014.

- Glynn S. Lunney. Interviewed by Roy Neal. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 9 March 1998. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/LunneyGS_3-9-98.htm. Accessed May 31, 2014.

- Glynn S. Lunney, Interviewed by Carol Butler. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 8 February 1999. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/LunneyGS_3-9-98.htm. Accessed May 31, 2014.

- Personal email to the author by Gene Kranz, July 5, 2014.

- Interview with Glynn Lunney, August 5, 2014.

- Vindu Goel, “Yahoo Wants You to Linger (on the Ads, Too).” The New York Times. June 21, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/22/technology/yahoo-wants-you-to-linger-on-the-ads-too.html?hpw&rref=technology. Accessed June 21, 2014.

- Carl L. Becker, “Annual address of the president of the American Historical Association, delivered at Minneapolis, December 29, 1931.” From the American Historical Review 37, no. 2, p. 221–36. http://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/presidential-addresses/carl-l-becker. Accessed May 15, 2014.

- In his correspondence with the author, Kranz wrote “The culture of its leaders is well done and readily evident in your article…. and I am afraid with the loss of the NASA mission we will have lost what made our early space ventures a success.”

- Gene Kranz. Failure is Not an Option. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2000. p. 376.

- Glynn S. Lunney, Interviewed by Carol Butler. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 26 February 1999. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/LunneyGS/LunneyGS_2-26-99.htm. Accessed May 31, 2014.

- Jerry C. Bostick, Interviewed by Carol Butler. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Marble Falls, Texas – 23 February 2000. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BostickJC/BostickJC_2-23-00.htm. Accessed May 26, 2014.

- Sy Liebergot with David M. Harland. Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Apogee Books: 2003. p. 114.

- Christopher C. Kraft, Jr., Interviewed by Rebecca Wright. NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Edited Oral History Transcript. Houston, Texas – 23 May 2008. http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/KraftCC/KraftCC_5. Accessed May 31, 2014.

- Gene Kranz “Our Time.” In Alan Bean, Painting Apollo. Washington DC: Smithsonian Books, 2009. In his correspondence with the author, Kranz wrote “The culture of its leaders is well done and readily evident in your article…. and I am afraid with the loss of the NASA mission we will have lost what made our early space ventures a success.”

- Interview by the author with Jerry Bostick. May 14, 2014.

- https://www.facebook.com/groups/spacehipsters/

- Dakota Creek Industries, Inc. “R/V Sally Ride.” http://dakotacreek.com/dci/projects/new-construction/rv-sally-ride-agor/. Accessed June 20. 2014.

- Personal emails to the author from Kate Doolan, June 20, 2014.