Orion’s time finally arrivesby Jeff Foust

|

| “EFT-1 is absolutely the biggest thing that this agency is going to do this year,” said Hill. |

Now, as the year 2014 enters its final month, that statement has not held up very well. NASA has no plans for a human lunar landing in 2020 or later; that goal of the Vision for Space Exploration was scrapped by the Obama Administration in 2010. Even before that decision, the first crewed Orion flight had officially slipped to at least 2015, and the 2009 Augustine Committee concluded it would likely not take place until at least 2017.

Orion, at least, will be flying in 2014, having survived the near-death experience of the cancellation of Constellation in 2010. It won’t be carrying people, and it won’t be going to the Moon, but it is scheduled to lift off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket at 7:05 am EST (1205 GMT) December 4. The flight, designated by NASA as Exploration Flight Test 1 (EFT-1), will last just four and a half hours, making nearly two full orbits of the Earth before splashing down in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Baja California.

That doesn’t sound like much of a flight, but NASA is making a big deal of the upcoming mission, calling it a major milestone in Orion’s development. Thousands of people—many working for Lockheed Martin and other companies working on Orion, as well as some space enthusiasts—are expected to converge on the Cape to witness the launch.

“EFT-1 is absolutely the biggest thing that this agency is going to do this year,” said NASA deputy associate administrator William Hill at a briefing about the mission at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) last month.

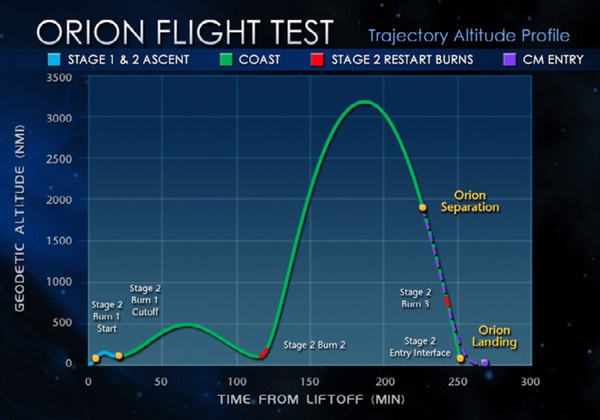

EFT-1 will follow a unique trajectory on its 4.5-hour test flight, going up to an altitude of nearly 6,000 kilometers before reentering. (credit: NASA) |

“You can’t do a test like that on the ground”

It’s a big deal since it’s the first time that an Orion spacecraft has flown in space. Over its long development process, Orion spacecraft and their subsystems have been scrutinized in clean rooms and high bays. Boilerplate versions of Orion have dropped from airplanes to test its parachutes, dunked in water to test its seaworthiness, and fished from the ocean to test recovery techniques. One even flew—briefly—on a test of its abort motor in 2010, flying a couple thousand meters into the air at White Sands, New Mexico, before parachuting back to the desert floor minutes later.

Some things about Orion, though, can’t be tested on land, sea, or air. “EFT-1 is basically a compilation of the riskiest events we’re going to see when we fly people,” Mark Geyer, NASA Orion program manager, said at last month’s briefing at KSC. “Some of these events are difficult or impossible to test on the ground.”

| “You can’t do a test like that on the ground. This is the test that we need to do to test this heat shield,” said Henning. |

The Delta IV Heavy, the most powerful rocket currently available to NASA, will place Orion and the rocket’s upper stage into an initial orbit of 185 by 888 kilometers. (The launch time, just a few minutes after sunrise, is driven by operational issues: it ensures the launch is illuminated, while maximizing the daylight available to the recovery team in the Pacific.) That orbit will serve as a checkout period for the spacecraft before it enters the next, and more daring, phase of the flight.

One hour and 55 minutes after liftoff, after Orion completes that first orbit of the Earth, the upper stage will fire its RL10 engine again for nearly five minutes. “It’s going to give us the hardest possible push it can give us,” said Garth Henning, Orion program executive at NASA Headquarters, at a Space Transportation Association luncheon in Washington last month. “It’s going to push the Orion as high as we can possibly get.”

That altitude is about 5,800 kilometers, high enough to send Orion through the lower portions of the Van Allen radiation belts. Orion will reach that peak altitude about an hour after that maneuver, and about 20 minutes later the Orion command module, descending towards the Earth, will separate from the upper stage.

Four hours and 13 minutes after liftoff, Orion will reach the “entry interface,” where the spacecraft’s reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere will begin. Traveling at about 32,000 kilometers per hour—faster than a normal reentry from orbit, and about 85 percent the reentry speed from a lunar return—that reentry will put to the test Orion’s heat shield, which at five meters across is the largest such heat shield ever flown.

“The primary objective here is the heat shield test,” Henning said, noting temperatures during reentry will reach 2,200 degrees Celsius. “You can’t do a test like that on the ground. This is the test that we need to do to test this heat shield.”

That heating will be brief, though, as Orion quickly slows. Six minutes after entry interface, with Orion slowed to subsonic speeds, it will deploy two drogue parachutes, followed a minute later by three main parachutes. Orion will splash down in the Pacific a few minutes later, or four hours and 23 minutes after liftoff from Cape Canaveral.

While testing that heat shield is a primary objective of EFT-1, driving its unusual flight profile, it’s not the only purpose for the flight. Geyer said the mission will test several other key systems, such as those needed to separate various components in flight, like the launch abort system during ascent. Passage through the Van Allen belts will test the susceptibility of Orion’s electronics to radiation effects. The mission will also provide a full test of the spacecraft’s parachutes. “It’ll be our first chance to make sure everything deploys and operates as it should,” Geyer said.

A main purpose of the EFT-1 flight is to test Orion’s heat shield during a reentry at speeds about 85 percent that of a return from the Moon. (credit: NASA) |

The unique nature of EFT-1

The EFT-1 mission is designed to test out many key technologies needed for Orion’s future missions. NASA officials say that the flight will test 10 of the top 16 risks that could lead to the loss of a crew. This mission, though, will be different from those future crewed Orion missions in a number of ways.

| “It’s somewhat unique for this mission. NASA’s asking for a service and we’re providing the data back,” said Lockheed’s Austin. |

First involves Orion itself. “We are flying a flight primary structure, so you could fly people with this primary structure. You could fly people with this heat shield,” Geyer said. However, he said that engineers have found ways to reduce the structure’s mass that will be implemented on future missions. The vehicle’s launch abort system also won’t have an abort motor on this flight, since there is no crew on board.

Also, with no crew on board, much of the interior of Orion is not outfitted for EFT-1. For example, this Orion has no seats for a crew, nor displays and other controls that astronauts on board would use, Geyer said.

Even Orion’s exterior will look different. Illustrations and animations of Orion show it with a white exterior, courtesy of thermal paint. But the Orion flying on EFT-1 will instead look black. Henning explained that, given the short duration of the flight, that paint isn’t needed. “It’s just the raw black tile,” he said.

This Orion will also lack a full-fledged service module; in fact, the command module will remain attached to the upper stage for all but the last hour of the flight. The European Space Agency is supplying the service module for the next Orion mission, Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1), using technology developed for the Automated Transfer Vehicle spacecraft that services the International Space Station. ESA awarded a contract to Airbus Defence and Space on November 17 to serve as prime contractor for the service module.

Also different, of course, is Orion’s launch vehicle. With the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket that will launch future Orion missions still at least three years away from its first flight, the Delta IV Heavy was the best option available to do an interim flight test before SLS launches Orion on EM-1.

Less visible than the launch vehicle and the appearance of Orion, though, is how the EFT-1 mission is being carried out. While widely seen as a NASA mission, it is more accurate to say that EFT-1 is a mission for NASA being conducted—and led—by prime contractor Lockheed Martin.

“We took a different approach with EFT-1. We’re basically buying services from Lockheed Martin,” said Hill. “They are responsible for the mission. It is truly a commercial endeavor.”

“It’s somewhat unique for this mission. NASA’s asking for a service and we’re providing the data back,” Bryan Austin, the Lockheed Martin EFT-1 mission manager, at last month’s KSC briefing.

That approach—Lockheed Martin running the mission, and providing the data to NASA—manifests itself in a number of ways. For example, because this launch is being conducted by Lockheed at not NASA, United Launch Alliance had to obtain a commercial launch license for the Delta IV Heavy, a rocket previously used for national security missions. Lockheed also had to get a commercial reentry license from the FAA for Orion.

Both NASA and Lockheed Martin, though, emphasize that the space agency will have plenty of insight into mission operations through the use of “blended teams” of company and agency personnel. “You’re going to have all of the folks at the Cape all in the same room,” said Henning. “A Lockheed person will be chairing the meeting, but it’s going to be all the same folks with all the same insight.”

An uncertain future

While not technically a NASA mission, the agency has been heavily publicizing the mission, selling it as the next step towards the agency’s long-term goal of humans on Mars. NASA has promoted the mission through approaches both conventional and unconventional, including a partnership with the children’s television program Sesame Street. “The 10-day [EFT-1] countdown incorporates some of Sesame Street’s most beloved Muppet characters including Elmo, Cookie Monster, Grover, and Slimey,” NASA noted in a press release last week.

| “We’re going to be challenged to make December ’17,” Geyer said of Orion in August. |

But what comes after EFT-1 soon becomes vague. Orion’s next mission, EM-1, will be the first for the SLS. That mission is officially planned for late 2017. However, in August, a NASA cost and schedule model developed as part of a program milestone known as Key Decision Point C (KDP-C) estimated SLS would not be ready until as late as November 2018. That KDP-C estimate was known as a “70-percent joint confidence level model,” meaning that NASA estimates there is a 70-percent chance that SLS will be ready no later than November 2018.

At the time, NASA officials put a positive spin on that estimate, saying that the KDP-C review helped them identify problems that will help them be ready sooner. “If we don’t do anything, we basically have a 70-percent chance of getting to that date,” William Gerstenmaier, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations, said at the time. “We will be there by November of 2018, but I look to my team to do better than that.”

Orion has yet to pass its own KDP-C review, which is not planned until early next year. Thus, there’s no similar development schedule, or cost estimate, for Orion. However, a few weeks before NASA released the SLS review, Orion officials were hinting that they would be hard-pressed to be ready to fly in late 2017 regardless of the status of SLS.

“We’re going to be challenged to make December ’17,” Geyer said in an August 9 presentation at the annual Mars Society conference in Houston. He said the decision to add the EFT-1 flight test, as well as bringing ESA into the program to develop the Orion service module, were putting schedule pressure on the program.

However, he said there that the benefits of doing EFT-1 outweighed the schedule risks. “We felt it was more important to build a flight unit and fly it because we’re going to learn so much about what the risks are,” he said. “To us, it was worth the potential impact on EM-1.”

After EM-1 flies, be it in late 2017 or some time in 2018, will come EM-2, the first crewed mission for Orion. That is planned for 2021, most likely sending astronauts around the Moon, perhaps in the “distant retrograde orbit” around the Moon favored by NASA for its Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM), which seeks to nudge a small near Earth object into that orbit to be visited by astronauts.

However, assuming ARM goes forward, it appears increasingly unlikely that the asteroid would arrive in that orbit until about 2025, based on the candidate objects identified to date (see “Feeling strongARMed”, The Space Review, August 4, 2014). NASA is scheduled to decide later this month on which of two options it will pursue for ARM: redirecting an entire asteroid up to ten meters across into lunar orbit, or taking a smaller boulder off a larger asteroid and moving that into lunar orbit.

Yet, more than a year and a half after NASA announced ARM, it’s been slow to win support for it from both the scientific community and from Congress. The latter could weigh in on ARM later this month, if Republicans and Democrats in the House and Senate are able to develop a spending bill for NASA and other federal agencies for the remainder of fiscal year 2015. (The federal government has been operating on a stopgap spending bill, called a continuing resolution, since the fiscal year began October 1. That bill expires December 11, but Congress could choose to pass another short-term spending bill and defer action on the full spending bill until after the new Congress convenes in January.)

If Congress decides to delay or defund ARM, it’s not clear what mission would take its place in the early 2020s, at least within the budget profiles likely available to NASA for the foreseeable future. Complicating matters is the change of administrations in two years: the President who takes office in January 2017 will—eventually—turn his or her attention to NASA and may decide to revisit the agency’s plans, just as the Obama Administration did in 2009. That could raise new doubts about the future of Orion, SLS, and other elements of the agency’s space exploration architecture, even as the EM-1 mission approaches.

But then again, Orion has already survived one change in NASA exploration plans. Perhaps it can do so again, should the need arise.