Space resiliency: time for actionby Ethan Mattox

|

| However, the DOD has also realized that fielding smallsats creates some challenges within the space domain and, if not properly planned for, could compound the problem of space congestion. |

How would we deal with this situation? How would we overcome these challenges? While we can’t quickly replace or augment capabilities by launching new ones, there are existing small satellite, or smallsat, capabilities owned and operated by the Geographic Combatant Commands (GCC) that could help in such a situation. However, if today we had to quickly and effectively leverage those capabilities we would struggle to do so. Why is that?

As we look to answer that question, we must first understand why there is a move towards smallsat systems and the challenges associated with operating them. The Department of Defense (DOD) has come to realize that smallsats offer a relatively low-cost approach to meeting certain requirements for space-based support to military operations. Additionally, as some DOD organizations work through development and fielding of smallsat systems, they have come to realize that smallsats could be further leveraged to bolster the resiliency of US space capabilities. However, they have also realized that fielding smallsats creates some challenges within the space domain and, if not properly planned for, could compound the problem of space congestion.

This article first describes why the DOD is looking to employ smallsat systems and how those systems can improve the US space architecture as a whole. It then looks at the challenges posed by employing smallsats and the problem they pose to the space domain. The discussion then turns to provide a recommendation for a joint concept for smallsat employment that would address smallsat employment concerns and allow them to be effectively leveraged during contingency operations.

DOD interest in smallsats

As the DOD and our nation’s intelligence organizations continuously work to adapt and develop capabilities to meet the needs of today and tomorrow, they simultaneously struggle to do so in an increasingly challenging fiscal and political environment. While the military continues to see force drawdowns and cuts in budgets, they must strive to find a balance in meeting mission requirements and responsive resourcing. Likewise, the national intelligence agencies are facing similar budget cuts, which translate to increased competition among users of information provided by overhead collection systems. Development and fielding of large space systems is an expensive and timely endeavor that is further compounded by the cumbersome defense acquisition process. Requirements identified today may take ten to fifteen years to result in a fielded system capable of meeting those requirements. While efforts are made to accurately predict future requirements, it is a daunting and challenging task that often results in gaps in capabilities. Likewise, in a struggle to keep up with today’s dynamic operational environment, there are often immediate, short-term requirements that emerge that may not justify the expenditures on large-scale satellites.

To mitigate these issues, various DOD organizations have begun science and technology demonstrations with the goal of fielding smallsats that will be under the operational control of individual Combatant Commands (CCMDs) and, in some cases, controlled and tasked by warfighters at the tactical level. While some programs are still in the development stage, a few programs have already resulted in on-orbit capabilities. On June 29, 2011, the Department of Defense’s Office of Operationally Responsive Space (ORS) successfully launched the ORS-1 satellite as the first dedicated ISR asset providing critical imagery capability to US Central Command.1 US Special Operations Command also has a constellation of smallsats on orbit. Launched on November 19, 2013, the Prometheus cubesats will allow special operation forces to transfer audio, video, and data files from man-portable, low-profile, remotely located field units to deployable ground station terminals using over-the-horizon satellite communications.

Likewise, the US Army has also begun investing in smallsat technologies. On December 5, 2013, the Army’s Space and Missile Defense Command Nano-Satellite-3 (SNAP-3) was launched to provide beyond line-of-sight communications to US Southern Command forces.2 The Army is also developing tactically controlled imagery satellites like Kestrel Eye, which will provide soldiers with improved battlespace awareness. Smallsat sizes and weights have been flexible based on what launch vehicles can support. These smallsats are built on the scale of thousands of dollars, as opposed to the millions or billions invested in large-scale satellite systems. As a result, these smallsats offer a more responsive, affordable means of meeting joint warfighter requirements. As the DOD seeks to provide the warfighter with more responsive, tactically relevant capabilities, we can expect a continued growth in the fielding of smallsat capabilities across all of the services and CCMDs.

Space as a contested domain

While it may be their primary purpose, providing timely, tactically relevant services is only one of many advantages that smallsats offer. Smallsats could also serve as a viable means of augmenting the services provided by larger space systems, thereby providing both resiliency and disaggregation to existing space-based capabilities when needed. General William L. Shelton, former commander of Air Force Space Command, referred to the resiliency of space systems as “the ability of a system architecture to continue providing required capabilities in the face of system failures, environmental challenges, or adversary actions.”3 He further referred to space disaggregation as “the dispersion of space-based missions, functions or sensors across multiple systems spanning one or more orbital plane, platform, host or domain.”4

| The constellations of smallsats being fielded by individual combatant commands offer just that: a responsive and flexible means of strengthening our national space infrastructure as a whole. |

With the space environment becoming increasingly contested and competitive, the need for improved resiliency of our nation’s space-based capabilities has gained an increased focus in light of recent events. As our nation’s adversaries continue to develop capabilities which may challenge our superiority in space, we will no longer be able to operate unhindered in the space domain. The Chinese direct-ascent ASAT test conducted on January 19, 2007, further emphasized that space is becoming a contested domain and that our nation must properly prepare to meet the emerging threats to space-based systems.5

In his April 3, 2014, statement before the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, Lt Gen Raymond, Commander, Joint Functional Component Command for Space (JFCC SPACE), highlighted the need to prepare for tomorrow’s operational environment:

“As the barriers to access space are lowered, the number of actors is expected to increase, and our ability to carry out our missions will become progressively more difficult. A responsive and flexible global force must continue to exploit the advantages of space to ensure effective and efficient military operations.”6

The need to prepare for attacks in space does not just resonate in the voice of senior military officials. It’s also a concern voiced by those drafting national policy. The requirement to improve the survivability of space-based capabilities is specifically addressed in the National Security Space Strategy (NSSS), which states that “our military and intelligence capabilities must be prepared to ‘fight through’ a degraded environment and defeat attacks targeted at our space systems and supporting infrastructure.”7

The constellations of smallsats being fielded by individual CCMDs offer just that: a responsive and flexible means of strengthening our national space infrastructure as a whole. Smallsats in low earth orbit (LEO) are much smaller than traditional satellites and may maneuver more frequently. As a result, the ability to maintain highly accurate ephemeris (a mathematical model of the satellites motion) is reduced, thereby making them harder to target than single, large satellites. Additionally, they are also much cheaper and easier to replace than traditional space systems. Distributing satellite services across constellations of smallsats also reduces the overall operational impact of electromagnetic interference, adversary jamming, or other forms of attack that may disrupt satellite services. Such a disaggregated force of smallsats offers a great deal of potential to providing assured access to space capabilities during contingency operations, especially in the face of a near-peer’s ASAT capability. Disaggregating satellite services across dissimilar smallsats not only complicates an adversaries targeting solution, it also reduces the payoff of such an attack and therefore provides a degree of deterrence.

Space as a congested domain

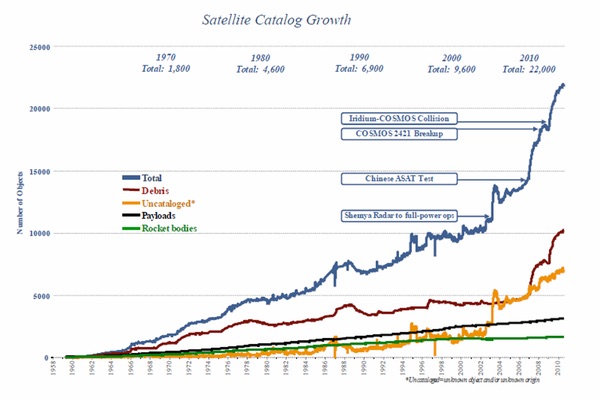

A contested space environment, however, is not the only concern. We must also be concerned with the rate at which the space environment is becoming congested. Both intentional and unintentional collisions in space have resulted in dramatic increases in orbital debris. The Chinese direct-ascent ASAT not only proved that China could hold our space assets at risk, it also created a debris field which continues to threaten manned and unmanned space operations.8 In 2009, the collision of Cosmos 2251 with Iridium 33 produced more than 2,000 pieces of orbital debris in low earth orbit (LEO).9 These events have placed significant challenges on our nation’s space surveillance network and highlighted the importance of improving our ability to gain and maintain space situational awareness (SSA).

Table 1: Satellite Catalog Growth from 1958-201010 |

Smallsats are further exacerbating the problem. The rapid advancements in solid-state electronics technologies have made it easier and cheaper to build smallsats using small-scale microprocessors and off-the-shelf components.11 As a result, we’ve seen a rapid growth in the number of universities, commercial industries, and government agencies investing in smallsat technologies. The extremely small size of these satellites makes them much more difficult to track and therefore requires the joint space community and JFCC SPACE to work together to effectively mitigate these challenges.

The NSSS states that the US will “enhance interoperability and compatibility of existing national security systems, across operational domains and mission areas, to maximize efficiency of our national security architecture”12 and “ensure these characteristics are built into future systems.”13 Subsequently, DOD Directive 3100.10 “Space Policy,” dated October 18, 2012, also states that the DOD will “support the development of international norms of responsible behavior that promote safety, stability, and security in the space domain.”14 . While this addresses the need to work closely with other nations, it can be argued that we are not effectively doing that today within the DOD joint space community as we have not fully defined a set norms or standards that apply to DOD employment of smallsats.

| If we had to leverage the existing small, tactical satellites on orbit today in a responsive, synergistic effort to augment the loss in service from one or more of our larger space assets, we would struggle to efficiently do so. |

As it stands, DOD organizations in the process of fielding tactically controlled satellites have no clearly defined requirements or methods to provide satellite ephemeris and other critical SSA supporting data. As a result, their ability to effectively and efficiently command and control smallsat systems is hindered by their struggle to identify threats to their assets and the lack of a complete operational picture when attempting to resolve anomalies. If we continue with the status quo, the result will be a diversity of non-integrated and “stovepiped” architectures, thus negating operational efficiencies and cost savings that could be realized.

What is missing?

While smallsats offer great potential towards strengthening the nation’s space infrastructure, if we had to leverage the existing small, tactical satellites on orbit today in a responsive, synergistic effort to augment the loss in service from one or more of our larger space assets, we would struggle to efficiently do so. This is largely because the joint community currently lacks a well-defined operational level concept and framework that allows the warfighter to maintain tactical command and control of smallsat constellations while simultaneously integrating those assets with JFCC SPACE to improve SSA and resiliency of existing space-based systems. Without well-defined JFCC SPACE reporting requirements and a framework that enables integration of smallsat platforms into existing SSA architectures and processes, these expanding constellations of space assets will not be leveraged to their maximum potential, nor will they be able to augment “big space” assets if and when needed during contingency operations.

The need for increased tactical ISR and communications capabilities will continue to grow across all CCMDs as we strive to meet the needs of the joint warfighter operating in today’s highly dynamic security environment.15 The CCMDs have a broad range of responsibilities and operational environments that require reliable C2 capability and up-to-date ISR. However, the proliferation of smallsat constellations to answer these needs comes with its own challenges. The lack of operational level SSA data requirements and integration of these assets will yield chaos and inefficiency if not addressed sooner rather than later. The lack of positional awareness and system capabilities will hinder both the SSA mission and any attempt to augment the services provided by larger space-based assets should the need arise. Redundant ground control architectures will continue to be developed in a way that meets the needs of the joint warfighter but will provide no contribution to SSA or resiliency of US space-based capabilities. Furthermore, this will pose an increased threat to the space domain and negate operational efficiencies and cost savings that could be realized from collaborative joint efforts.

Recommendation

The shortfalls identified here are not a problem just for JFCC SPACE. These shortfalls will impact the entire joint space community and everyone it serves. However, the development and implementation of a joint concept of operations (CONOPS) for DOD smallsat operations and standards of behavior could provide a solution that addresses both SSA and resiliency while establishing agreements and authorities in which all parties benefit. A joint smallsat CONOPS would clearly define what JFCC SPACE and the joint forces intend to accomplish with tactical satellites and how it will be accomplished using available resources. It would also identify the major capabilities required, major operational tasks to be accomplished by components, a concept employment, and assessment of risk associated with the concept.16

Such a joint smallsat CONOPS would:

- Define operational reporting procedures for constellations of smallsats

- Define data requirements to allow for improved SSA and space object tracking

- Define the means and formats by which reporting and passing of data is to occur

- Define under what conditions these tactically focused assets can augment national assets

- Define the norms for responsible smallsat operations

A joint smallsat CONOPS would provide JFCC SPACE with day-to-day insight into smallsat capabilities as well as ease the burden on the systems and personnel who struggle to maintain SSA. With a joint CONOPS in place, communication with the Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC), JFCC SPACE’s command and control center for SSA data provided by the Space Surveillance Network (SSN), would be formalized and covered by policy and mutual agreements. In doing so, the result would be better data exchanges, which would enhance accuracy of the space catalog and provide improved situational awareness to smallsat operators.

| A joint smallsat CONOPS would solidify the critical information exchanges and processes required to integrate smallsats into the existing space architecture. |

Smallsat tracking or position data would be provided to the JSpOC so that it may be used in conjunction with SSN data. This would help alleviate difficulty in tracking and differentiating smallsats which often get classified as “unknown objects” and do not get published to the space catalog. Preventing this situation benefits smallsat owner/operators in the conduct of their mission by enabling better command and control of their space assets and improving spaceflight safety. Coordination of pre-launch screening for conjunctions would also improve their understanding of the space environment and further reduce safety of spaceflight risk. Further benefits to the warfighter include:

- Improved interoperability and data exchange

- Accepted practices that reduce risk to tactically controlled satellites and help ensure mission success

- Increased reliability of space capabilities during major contingency operations

- Improved ability to avoid threats, safeguard assets, and mitigate electromagnetic interference

- Improved understanding of the environment and ability to develop courses of action in response to threats and anomalies

It is understandable that the CCMDs fielding tactical smallsat systems may have a natural reluctance to enter into such an agreement, as they may fear losing control of the asset in the long-term. However, there are existing command relationships and authorities that would prevent that from happening. The CCMDs have begun investing in smallsat capabilities to meet critical gaps in requirements. It is imperative that, in developing tactically-controlled space capabilities, the focus remain on putting those capabilities in the hands of and at the control of the warfighter.

It is also important that, during short-term contingency operations, space force planners balance the need for mission continuity and sustainment of operations against tactical force enhancement. The decision must be weighed as to whether or not to task a tactically-controlled space asset to support greater national objectives in lieu of the mission that it was originally intended to support. A synergistic effort between JFCC SPACE and the CCMDs would ensure overarching national security objectives are met first and foremost. The resulting enabling concepts would help shape the service-level requirements and acquisition processes by articulating necessary and supporting capabilities to produce desired effects that support warfighter and national objectives. Furthermore, joint efforts to establish a smallsat CONOPS would place the US in a leadership role in defining the norms for responsible smallsat operations.

In conclusion, recognizing the joint community’s dependency on space capabilities, we must improve our ability to maintain SSA and better prepare to counter our adversaries’ efforts to deprive us of the advantages afforded by our nation’s space-based assets. We must ensure that all space systems contribute to a more resilient and disaggregate space force. A joint smallsat CONOPS would solidify the critical information exchanges and processes required to integrate smallsats into the existing space architecture. It would establish norms for responsible smallsat operations that both reduces risk to tactically controlled satellites and ensures greater chance for mission success. The resulting synergy between JFCC SPACE and the CCMDs would allow smallsats to be leveraged in a way that improves resiliency of the nation’s space architecture and provide a “fight through” capability when needed.

Notes

- Stephen Clark, “Tactical spy satellite streaks into space on Minotaur rocket”. Spaceflight Now, June 30, 2011.

- Kenneth Stewart. “Southcom Turns to NPS to Evaluate CubeSats for Communications Support”, Naval Post Graduate School, January 22, 2014.

- Air Force Space, Command Resiliency and Disaggregated Space Architectures White Paper, 2013, 4.

- Ibid., 4.

- Brian Weeden, Through a Glass, Darkly: Chinese, American, and Russian Anti-satellite Testing in Space. Secure World Foundation, March 17 2014.

- Lieutenant General John W. Raymond, Fiscal Year 2015 National Defense Authorization Budget Request for Space Programs, Hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, May 9, 2014.

- Gates, R., & Clapper, J. National Security Space Strategy. Washington, DC: Secretary of Defense and Director of National Intelligence, 2011, 11.

- Leonard David, “China’s Anti-Satellite Test: Worrisome Debris Cloud Circles Earth.” SPACE.com, available February 2, 2007.

- Brian Weeden, 2009 Iridium-Cosmos Collision Fact Sheet. Secure World Foundation, November 10, 2010.

- Gates & Clapper, 1.

- David, 2013.

- Gates & Clapper, 6.

- Ibid., 6.

- Department of Defense (DOD), DOD Directive 3100.10 Space Policy, Washington, DC, October 18, 2012, 2.

- Hearing before the Committee on Armed Services Strategic Forces Subcommittee on Space Programs, Senate Armed Services Committee, 113th Cong. 2 (2014) (testimony of Lieutenant General David L. Mann).

- Joint Operations Planning, Joint Publication (JP) 5-0, Joint Operations Planning (Washington, DC: U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, March 22, 2010), xvi.