The limits of Cruz controlby Jeff Foust

|

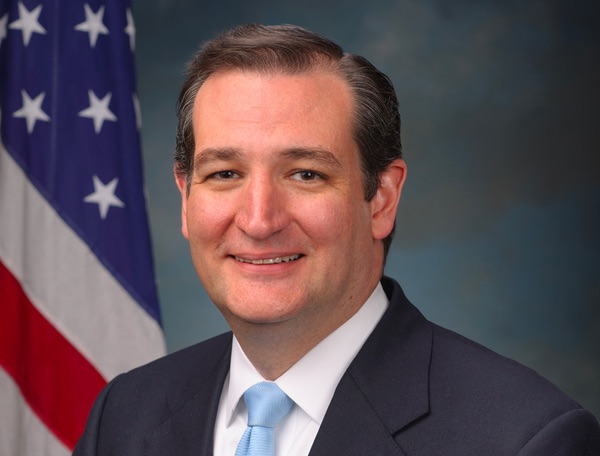

| That Senate subcommittee, responsible for NASA policy issues among other topics, does have a new chairman, and it’s that choice that’s generated the bulk of the space-related debate this month. |

Space advocates did get a brief thrill last week when President Obama mentioned space exploration briefly in his hour-long State of the Union address January 20. The comments, though, reflected current plans and activities and didn’t set any new direction for NASA. “Last month, we launched a new spacecraft as part of a reenergized space program that will send American astronauts to Mars,” he said, a reference to December’s Orion test flight. “And in two months, to prepare us for those missions, Scott Kelly will begin a year-long stay in space.” NASA itself wasn’t mentioned by name there, although it was mentioned in a later passage about the scientists at NASA, NOAA, and universities studying climate change.

Congress has also been slow to take up the issue, likely waiting for the administration’s 2016 budget request. They’ve been slow organizationally as well: while committee assignments for new and returning members were made weeks ago, some subcommittee rosters have yet to be filled out, like the space subcommittee of the House Science Committee and its counterpart in the Senate Commerce Committee, the Space, Science, and Competitiveness subcommittee (formerly just the Space and Science subcommittee.)

That Senate subcommittee, responsible for NASA policy issues among other topics, does have a new chairman, and it’s that choice that’s generated the bulk of the space-related debate this month. In many respects, the decision by Senate Commerce Committee chairman Sen. John Thune (R-SD) to have Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) chair the space subcommittee is not surprising. Cruz served as ranking member of the subcommittee in the last Congress, when Democrats held the majority; becoming chairman is simply an extension of his position as the subcommittee’s top Republican.

For some, though, the idea of Cruz running the subcommittee with oversight of NASA was anathema. Critics pointed to past efforts to cut funding (or, more accurately, authorization for funding) for NASA, and his opposition to the agency’s work in Earth sciences, particularly climate change research.

One example of that reaction was a commentary by Phil Plait, who writes the “Bad Astronomy” column for the publication Slate. “This is not a good thing,” he wrote of Cruz’s chairmanship (emphasis in original.) “Just how bad it is will be determined.”

| “We must refocus our investment on the hard sciences, on getting men and women into space, on exploring low Earth orbit and beyond, and not on political distractions that are extraneous to NASA’s mandate,” Cruz said. |

Cruz, in comments to the Houston Chronicle January 12, shortly after being named the subcommittee chairman, appeared to confirm those critics’ fears. “One of the problems with the Obama Administration is that it has degraded our ability for space exploration,” he said. “It has shifted the funding to global warming pursuits, rather than carrying out NASA’s core mission.”

A couple days later, Cruz’s office released a statement from the senator and his advocates outlining his position. “We should once again lead the way for the world in space exploration,” he said in the statement. “We must refocus our investment on the hard sciences, on getting men and women into space, on exploring low Earth orbit and beyond, and not on political distractions that are extraneous to NASA’s mandate.” He did not identify what those “political distractions” were.

In that statement, his supporters took a similar tack, often criticizing the Obama Administration for a perceived lack of leadership and support for NASA, but not identifying particular agency programs or priorities that might come under scrutiny by Cruz. “As ranking Republican member of the subcommittee last Congress, Sen. Cruz has demonstrated his recognition of the importance of the US Civil Space Program and the direction charted by Congress and embodied in the current law,” said Jeff Bingham, a former staff director for the subcommittee. “I am confident he will continue that balanced approach as he assumes the chairmanship of the subcommittee.”

In an interview with the Houston Chronicle January 14, Cruz didn’t discuss Earth science, but did mention his support for NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) and Orion programs, as well as its commercial crew efforts. He was, like a number of other members of Congress, more skeptical of NASA’s Asteroid Redirect Mission plans, saying the concept “has at times seemed to have had a changing and shifting focus.”

While many have written about their hopes for the best—or fears of the worst—of a Cruz chairmanship, much of that rhetoric overstates just how much influence he is likely to have over the next two years. The scope of his subcommittee, the realities of doing business in the Senate today, and even the potential of a 2016 presidential run will limit how much he will be able to shape NASA and its activities.

Much of what has been written has suggested that Cruz will be wholly responsible for NASA and its activities in the Senate, if not the entire Congress. “Simply put, Senator Cruz is now in charge of the NASA budget,” claimed one essay on a space-related site that carried the title “Ted Cruz is now the ‘Chairman of Space’”.

Simply put, that assessment is incorrect. Cruz’s subcommittee can develop and pass legislation to authorize NASA funding, and set other agency policy. However, real control of the NASA budget, in terms of actually allocating funding, is in the hands of the Senate Appropriations Committee (and, of course, its House counterpart.) Cruz does not serve on the Senate Appropriations Committee.

Authorization bills are important, in that they lay out plans and set spending levels that can advise appropriators who actually allocate the funds. The NASA Authorization Act of 2010, for example, established the compromise between the White House’s plans to cancel the Constellation program and that program’s supporters in Congress, one that created the SLS.

However, authorization bills are “nice-to-haves,” not “need-to-haves.” That is, while an authorization bill can be useful in setting policy and proposing spending levels, it’s not required for NASA to operate. The 2010 act, which authorized spending for fiscal years 2011 through 2013, is the last NASA authorization act passed by Congress. The policy provisions in that bill remain in effect, and NASA received funding for fiscal years 2014 and 2015 without an explicit authorization.

| While Cruz may be perceived as an agent of change in the Commerce Committee, the Appropriations Committee, which controls the purse strings, retains some familiar faces. |

Much of the criticism that Cruz has received for seeking to cut NASA funding stems from an amendment he proposed during a markup of a proposed NASA authorization bill the Senate Commerce Committee debated in July 2013. That amendment sought to reduce authorized spending levels to comply with the Budget Control Act, and to mirror the House’s version of that bill. “Proceeding with an authorization while pretending that the existing law is something other than what it is, is not the most effective way to protect the priority that space exploration and manned exploration should have,” he said in the committee’s debate about the amendment.

The amendment failed on a party-line vote, and the committee later approved the bill, also along party lines, but the legislation went no further in the Senate. That concern was later superseded by an agreement between House and Senate appropriators that set overall spending levels for 2014 and 2015, overriding budget sequestration.

While Cruz may be perceived as an agent of change in the Commerce Committee, the Appropriations Committee, which controls the purse strings, retains some familiar faces. Its Commerce, Justice, and Science, or CJS, subcommittee, which funds NASA among other agencies, is chaired by Sen. Richard Shelby (R-AL), with Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) as its ranking member. The two held each other’s positions on the subcommittee in the previous Congress, when Democrats were in control of the Senate.

Mikulski and Shelby, moreover, have a long record of working together on NASA funding issues, making sure their respective priorities win funding. Mikulski, also the ranking member of the full committee, would likely oppose any effort, within or outside the committee, to cut funding for Earth sciences work at NASA, given that much of that work is run by the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

Cruz could, of course, seek to press through changes in NASA policy using authorization bills or other legislation, taking advantage of the majority Republicans hold in the Commerce Committee. But, like the Democrats found in 2013, any bill that wins passage on a party-line vote in the committee is unlikely to be successful in the full Senate. In the procedures of the modern-day Senate, almost every bill requires at least 60 votes for passage.

That 60-vote requirement is for legislation important enough to warrant floor debate: lower-priority bills, like a NASA authorization, typically must make use of a procedure called unanimous consent, which streamlines passage for bills provided no member of the Senate objects. Some members of the Senate tried to get a NASA authorization bill passed that way last fall, to allow it to be conferenced with one approved earlier last year by the House, but were unable to get all members on board before the session ended.

There’s also the question of how much time Cruz will devote to the topic of space, given all the larger policy issues up for debate this year. In addition, Cruz has ambitions for higher office: he was in Iowa this past weekend for an event that featured a number of people expected to run for the Republican nomination for President in 2016. If Cruz does put his hat into the ring, he’ll be spending much of the next year in places like Iowa and New Hampshire, and less time devoted to space policy.

| In his Houston Chronicle interview, Cruz said that “one of the first priorities of the subcommittee will be to take up reauthorization of the Commercial Space Launch Act precisely to continue fostering an atmosphere of innovation and competition.” |

So what could Cruz do in his role as subcommittee chairman? He will be able to hold hearings on various space policy topics, from human spaceflight to Earth sciences, shining a spotlight on topics he feels are important. Those efforts may not translate into legislation that can make it through the Senate, but can raise awareness of potential issues—at the very least, what a Cruz Administration might do differently.

He can also take on less controversial legislation. In his Houston Chronicle interview, Cruz said that “one of the first priorities of the subcommittee will be to take up reauthorization of the Commercial Space Launch Act precisely to continue fostering an atmosphere of innovation and competition.” Key members of the House Science Committee have previously said they were interested in updating that act this year, which appears unlikely to have strong opposition.

Thus, depending on your point of view, Sen. Cruz’s chairmanship of the space subcommittee is unlikely to be as good—or bad—as many have argued. He may be able to help push through less controversial changes in space policy, like an update to the commercial launch act, that many see as overdue. Major changes to NASA’s programs or funding, though, are far less likely. At the very least, it should give space advocates an opportunity to find out what one 2016 contender for the White House thinks about space.