The Earth, Moon, Mars, and Christopher Columbusby Rex Ridenoure

|

| Such a voyage, however attempted, will have certain parallels to earlier human voyages. |

Recent proclamations by NASA, those in our government who shape NASA’s programs, private companies and organizations in the US and abroad (with variable credibility), and even the occasional Hollywood drama have largely squelched the giggle factor associated with this audacious goal.

Humans to the Red Planet? It seems it’s no longer a matter of if, but when—and how. There is a general consensus that a young person already living today will be the first to set foot there. And more will follow.

Sending humans to Mars is surely going to be a bold, daring and risky venture—not to mention as epically historic as human events ever can be. Such a voyage, however attempted, will have certain parallels to earlier human voyages.

A first-order concern of any human trip to Mars is simply the trip time involved. Trip time drives cumulative water, food, and oxygen consumption by the crew; duration of exposure to the microgravity (or artificial gravity) environment; space radiation dosages; evolution of crew interpersonal relations and psychology; and sheer distance from home.

To compare and contrast such a trip to an earlier pioneering human voyage, let’s look at the first voyage across the Atlantic of Christopher Columbus and his small fleet: the Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria. Trip time was also a key driver of this voyage, because more sailing time meant a greater need for fresh water and food, more exposure to the sea and the elements and what this does to the crew and the ships, more frayed nerves and anxiety, and perhaps even more scurvy.

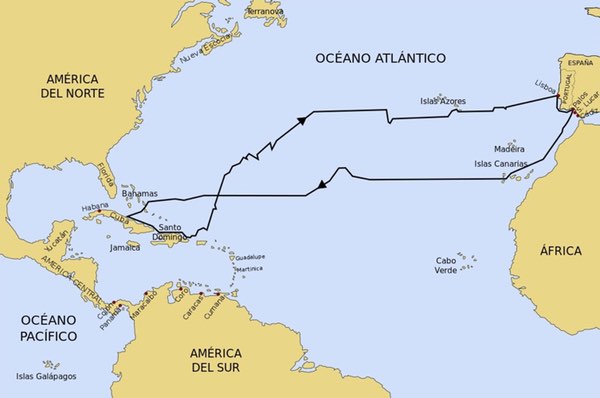

Columbus and his crew sailed from the Spanish port near today’s Huelva headed southwest, and six days later stopped at the Canary Islands for a month of repairs, restocking, rest, and planning. His tiny fleet then sailed pretty much due west from there, headed for the East Indies—but actually landing in what is today some island (no one knows for sure which) in the Bahamas.

Total trip time from the Canaries to the “New World”: five weeks.

Columbus’ first voyage to The New World in 1492. (Credit: from the Wikipedia article “Christopher Columbus,” image file Viajes_de_colon.svg.) |

Launch, propulsion, and orbital mechanics nuances aside, one-way trip times to various destinations in space cluster around some fairly standard durations (all approximate here):

- Launch to LEO: 10 minutes

- Launch to ISS docking: 6 hours (using “fast rendezvous” perfected by the Russians and Soyuz)

- LEO to GEO: 12 hours

- LEO to the Moon: 3–5 days (the fast way, using standard orbit-transfer techniques)

- LEO to the Moon: 3–5 months (the slow way, using low-energy orbit-transfer techniques)

- LEO to Mars: 6 months (the fast way, using standard orbit-transfer techniques)

Now for context, what if we use these same one-way trip times and apply them to Columbus and his adventurous crew? Thanks to the website Sea-Distances.org, we can get the numbers. Setting sail once again, where would they find themselves after their time was up?

- Launch to LEO: Probably just made it out of port

- Launch to ISS docking: Half-way to Gibraltar (Cadiz?), along the Spanish coast to the southeast

- LEO to GEO: All the way to Gibraltar

- LEO to the Moon (fast way): The Canary Islands

- LEO to the Moon (slow way): One or two round trips to The New World

Before I get to the really fun and adventurous trip—the trip to Mars—I’ll make a couple of basic assumptions:

- Columbus’ fleet sails along at the same speed as all the other trips above, with no stops along the way

- The Panama Canal does not exist

Okay, Mars pioneers and settlers, here you go!

- LEO to Mars (fast way): All the way from Spain to the Philippines via the southern tip of South America (Cape Horn), and then all the way back to Spain, and then all the way back to the Philippines again. So we might characterize the journey as a “Triple Philippines” trip.

| A human trip to Mars would truly be a Grand Voyage, requiring a Triple Philippines ticket, while a quick jaunt to the Moon is akin to Columbus and crew with their layover in the Canary Islands. |

Magellan and his crew of 237, loaded on five ships, were the first to sail this route in 1519–1521, during the first attempt to circumnavigate the globe a generation after Columbus’ first voyage. They made many stops along the way, and Magellan himself was killed in the Philippines near today’s Cebu and never completed the journey. In fact, only one ship with 18 men did. And this was just a single Philippines trip.

This comparison highlights some of the key differences between seeking near-term human trips to Mars vs. the Moon. A human trip to Mars would truly be a Grand Voyage, requiring a Triple Philippines ticket, while a quick jaunt to the Moon is akin to Columbus and crew with their layover in the Canary Islands.

One could argue that the Canary Islands actually served as Columbus’ departure point to The New World, while the brief trip from Spain to the Canaries was just a “fleet systems test” or a prelude to the actual journey.

Spirited arguments are raging today about whether we should treat the Moon as our “Canary Islands” to the solar system and develop it first, or whether making human sprints to Mars (round-trip or one-way) is a more worthy goal of our bold species, Moon be damned.

When we talk about monetizing the Red Planet, what makes more sense?

There is an interesting irony here, too.

In Columbus’ day the Canary Islands were already bustling with people, commerce, and logistics, while The New World was unknown and unexplored by Western Europeans. Today, the Moon—our nearest neighbor—is virtually uninhabited, with only a few operating robots serving in our stead decades after a few fortunate humans had visited and left some flags, footprints, and now-historic junk.

And as for Mars, we know much about this remote world a Triple Philippines away, and our robot scouts are busy gathering more and more information every day, from which we can infer even more knowledge. It is both known and explored—at least partially.