Humans to Mars: further delay undermines supportby Joe Webster

|

| From a programmatic basis, these dates are not desirable because they are so far in the future that they are unlikely to be sustainable politically or with the public. |

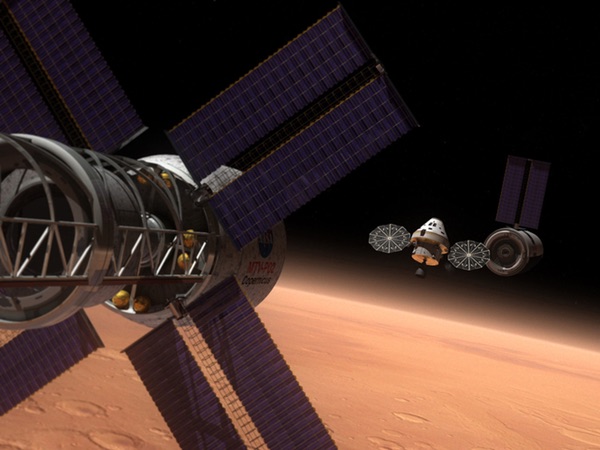

For the first time, there is a growing consensus within the space advocacy community that human missions to Mars should be the goal of the US space program. There are still details to resolve about the overall mission architecture, however, including the role of precursor missions. For example, at the recent workshop organized by the Planetary Society and the Space Policy Institute, a concept developed by JPL for a mission to Mars orbit received significant support. As presented, the mission would be conducted as a precursor to a mission to the Martian surface, which would follow shortly after the orbital mission.

While the concept of a precursor mission to Mars orbit has great merit, the workshop limited its consideration to what could be accomplished with an inflation-adjusted flat NASA budget for the next 25–30 years. Based on this assumption, the study concluded that a mission to Mars orbit could be conducted by 2033, with a mission to the surface of Mars by the end of the 2030s or even the early 2040s.

However, these dates are conservative estimates based on pessimistic funding levels. From a programmatic basis, these dates are not desirable because they are so far in the future that they are unlikely to be sustainable politically or with the public. The space community is keenly aware that NASA has been telling the public that Mars is 20 years away for nearly 50 years. During that time, tens of billions of dollars have been spent to advance technologies that supposedly were going to bring us closer to Mars. After so many years and spending so much money, the public (who pays the bills) would be justifiably skeptical if NASA were to claim, yet again, that Mars is 20–25 years away.

The reality is that good programs attract funding, especially if the programs are well designed and well managed. Thus, the challenge for the space advocacy community is to convince the policy makers to fund a well-designed Mars exploration architecture at a level that will allow the program to be carried out within a politically viable timeframe. Such an architecture almost certainly will contain a number of precursor missions, such as a mission to Mars orbit and possibly a Mars flyby mission.

| A well-defined architecture with near-term precursor missions and a Mars landing in less than 20 years is much more likely to generate public and political support than a timeline that defers any mission to Mars for yet another generation. |

Explore Mars and others have been encouraging the development of an affordable architecture. Based on the studies conducted to date, an accelerated schedule is possible without major increases in NASA's budget. For example, funding increases of only a few percent above inflation might allow precursor missions, such as a Mars orbit mission, to take place in the 2020s, with a Mars landing possible by the early 2030s. Such a timeline is much more likely to attract funding and support from the public. It is much easier to cancel a program that in not scheduled to launch a mission for 20–25 years than one that is scheduled to start sending missions to Mars within only a decade.

Of course, we can’t assume any funding increases for NASA. It will require significant efforts over many years to achieve any increased funding. However, a well-defined architecture with near-term precursor missions and a Mars landing in less than 20 years is much more likely to generate public and political support than a timeline that defers any mission to Mars for yet another generation. We have been trying that approach for nearly 50 years, and it simply does not work.

All these topics will be thoroughly discussed at the upcoming Humans to Mars Summit.