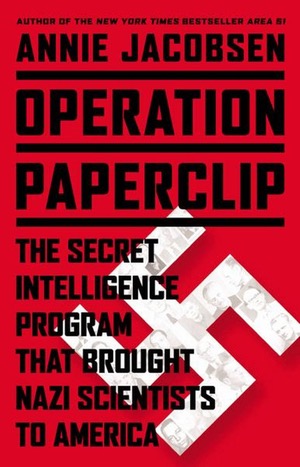

Review: Operation Paperclipby Michael J. Neufeld

|

| Jacobsen also misidentifies Third Reich leaders and organizations, gets the details of the reorganization of the US military in 1947 wrong, and misspells the name of famous diplomat George F. Kennan in every reference to him. It leads me to doubt the accuracy of every story in the book that I do not know so intimately. |

My negative impression of her accuracy set in early. On page 7, she calls the V-1 cruise missile the V-2’s “earlier version.” On page 8, she writes that the military leader of the German Army rocket program, Gen. Walter Dornberger, “often wore a long-shin-length leather coat to match the Reichsführer-SS [Heinrich Himmler]”—a ludicrous detail, as Dornberger wore Wehrmacht standard issue. I have written extensively about Dornberger’s collaboration with the SS in the criminal enterprise of the concentration camps connected to the V-2 program, but also about the Army-SS rivalry in the program—Dornberger was no toady of Himmler.

The next several pages are an overwritten scene of Albert Speer’s presenting the Knight’s Cross to Dornberger, von Braun, and two others, based on my quotations and summary from Dornberger’s memoir. But in the process Jacobsen adds many invented details for dramatic effect. On page 13, she describes von Braun associate Arthur Rudolph (best known for being forced to leave the United States in 1984 over his involvement with the Mittelwerk V-2 factory), as a “high-school graduate,” even though he had a two-year engineering technology degree. It is a minor error, but when multiplied by a hundred it casts doubt on the whole. In my primary area of expertise, the V-2 and von Braun, every discussion of these stories throughout the book is error-ridden. Jacobsen also misidentifies Third Reich leaders and organizations, gets the details of the reorganization of the US military in 1947 wrong, and misspells the name of famous diplomat George F. Kennan in every reference to him. It leads me to doubt the accuracy of every story in the book that I do not know so intimately.

The lack of any fundamentally new information is also troubling. I do not mean that there is nothing new in the book or that it is without value. Operation Paperclip is very readable and it covers many stories told in the previous literature better than they were before. Jacobsen found new sources to interview and she and her researchers (of which she lists several) have been to archives that Linda Hunt and Tom Bower, the two primary journalists of the earlier phase, have not cited.1 But much space is devoted to colorful and interesting descriptions of the various Allied holding facilities for Nazi leaders, the war crimes trials in Germany, and the growth of the Gehlen Organization (the ex-SS-dominated intelligence group in the US occupation zone that became the West German intelligence agency BND.) Most of this information is only tangentially related to Operation Overcast (the original name) or Paperclip.

A large fraction of the book concentrates on chemical and biological warfare and aerospace medicine, subjects that continue to shock in the willingness of members of the US military to recruit Third Reich specialists connected to concentration-camp experiments on inmates, while covering up or whitewashing the Nazi records of those they recruited. Jacobsen develops these stories more than Hunt or Bower did, but I did not find anything that struck me as fundamentally new. The author herself acknowledges the pioneering work of Linda Hunt in using the Freedom of Information Act to produce much new information in the 1980s. Her own contributions to research seem slight by comparison.

Jacobsen, following the tradition of Hunt and Bower, concentrates on the scandals, which inevitably leads to an imbalance in presentation. Little is said about the substantive contributions of von Braun and company to US ballistic missile and space programs, and the same is true of the specialists the US Air Force recruited—numerically the largest group taken by any of the services. (She of course uses the clichéd but ominous-sounding term “Nazi scientists,” although the majority were engineers and many were not members of the Nazi Party, SA or SS.)2 Even in the case of the frightening and repulsive cases of nerve gas and biological weapons development, was it in the US national interest to walk away from those weapons (and some of the people needed to acquire expertise in them), knowing that the Soviet Union would get that knowledge too? The Cold War led to some appalling moral compromises but it had a deterministic arms-race logic that was difficult to escape. Jacobsen calls Paperclip a “nefarious child of the Second World War” that “created a host of monstrous offspring” (page 371). Black-and-white judgments are easy—and a tradition for this topic—but it hardly leads to a balanced assessment.

| Operation Paperclip is not the book that the scholarly world, or the general public, need on this topic. A new study is needed, one informed by new historiographic perspectives, as well as by all the archival sources that have become available. |

As for the notes, they are in the unfortunate trade-press tradition of page references in the back, primarily for quotations—but not even consistently for those. Despite the impressive looking bibliography, the notes are mostly to secondary sources, and proper archival citations to Paperclip and other documents are never given—that too continues the tradition of Hunt and Bower. And I cannot help remarking that, when she uses a note to make an (irrelevant) aside about the bombing of Auschwitz question (regarding John J. McCloy, who was US High Commissioner to Germany in the early fifties), it has at least two factual errors (page 518).

Operation Paperclip is not the book that the scholarly world, or the general public, need on this topic. It is unfortunate that the first scholarly work, by Clarence G. Lasby,3 remains the only balanced one, although it is completely dated by the revelations of the 1980s and the scholarship that has appeared since. A new study is needed, one informed by new historiographic perspectives, as well as by all the archival sources that have become available. I am not going to write that book, so I hope somebody does. It could make a fruitful doctoral dissertation.

Endnotes

- See Linda Hunt, “U.S. Coverup of Nazi Scientists,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (April 1985), 16–24, and Secret Agenda: The United States Government, Nazi Scientists and Project Paperclip, 1945 to 1990 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991); Tom Bower, The Paperclip Conspiracy. The Battle for the Spoils and Secrets of Nazi Germany (London: Michael Joseph, 1987). See also Christopher Simpson, Blowback: America's Recruitment of Nazis and the Its Effects on the Cold War (New York: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1988), which focuses primarily on the CIA and intelligence.

- I decided that the Soviet term “specialists” was more useful in my global survey of the recruitment of German and Austrian aerospace experts: “The Nazi Aerospace Exodus: Towards a Global, Transnational History,” History and Technology 28 (2012), 49–67.

- Project Paperclip: German Scientists and the Cold War (New York: Atheneum, 1971). Also valuable from an occupation-centered perspective is John Gimbel’s Science, Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Postwar Germany (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990).